Monday Musicale with the Maestro – October 26, 2020 – In Search of the Great American Symphony, Part 2

George Whitefield Chadwick (1854-1931)

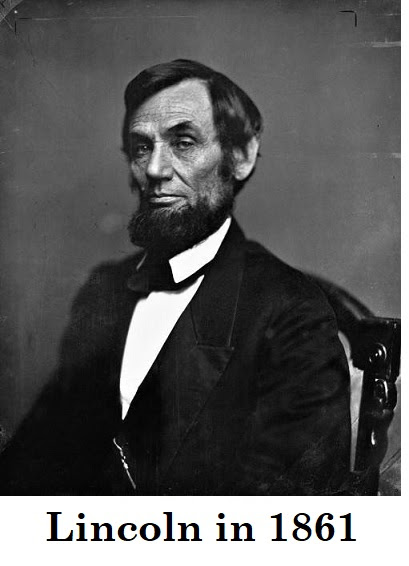

Classical music was slow to take root in 18th-century America. And when it did begin to flourish, it did so mainly in New England, New York City, and Philadelphia. The first great American composer was William Billings (1745-1800). Billings (whom we’ll explore further in a future Monday Musicale) was known for his choral works and was the most notable member of what’s come to be known as “the First New England School of Composers.” New England was also notable for the first fledgling opera companies and symphony orchestras. By the middle of the 19th century, operatic performances were especially popular. It is not commonly known, for example, that Abraham Lincoln was an opera fan!

The first opera Lincoln saw was in New York City in 1861 when he attended the American premiere of Verdi’s A Masked Ball and was immediately hooked! Over the next four years, he saw over 30 operatic performances. In a wonderfully perceptive statement quoted by White House historian Elise K. Kirk, Lincoln observed that “‘Listening to a melody, every man becomes his own poet and measures the depth of his own nature.’” (“Music In Lincoln’s White House,” whitehousehistory.org)

The Second School of New England composers included John Knowles Paine, Horatio Parker, and today’s feature composer, George Whitefield Chadwick (1854-1931).

Like most American composers prior to the 1950s, Chadwick studied music in Europe. During his three years in Germany, he focused mainly on composers of the Austro-German tradition, especially Schumann and Mendelssohn. In the 1880s, as American composers first began experimenting with music related to their homeland, Chadwick’s music slowly evolved from imitation to his own unique blend of European music with American songs and dances. His first orchestral piece was Rip van Winkle; a tone poem based on Washington Irving’s famous tale from The Sketch Book (1819-20). At its premiere in Boston (1879), the tone poem was praised by both musicians and critics. And over the next 50 years, Chadwick created a remarkable catalogue of music in every form, including symphonies, tone poems, chamber music, art songs, an opera, and one of the earliest musicals—a comedy titled Tabasco (1894), sometimes rendered as The Burlesque Opera of Tabasco.

Chadwick was also a great music educator. As director of the New England Conservatory of Music, he was a trailblazer in admitting women and minorities. And as a professor of composition, his students included William Grant Still and Florence Price, composers who would go on to write the first symphonies by African Americans. According to family lore, my father’s mother (Mahulda Moody) received a scholarship from the Conservatory to be an organ major there, but she was unable to attend due to the birth of my father.

Chadwick’s three symphonies are more conservative and derivative than many of his other works. He was writing during an era when the word symphony automatically connoted a grandeur, depth, and substance such as that found in Beethoven’s most epic works. Chadwick’s symphonies—though beautifully constructed—fall short in conveying the Beethovenian model of artistic struggle or grand philosophical reflections. Chadwick may have understood this himself, for after completing his third (and final) symphony in 1893, he wrote what he called his three “little symphonies”: Symphonic Sketches (1895-1905), Sinfonietta (1908), and the Suite Symphonique (1910). In these works, Chadwick was able to adopt a congenial style that reflected his wry, Yankee sense of humor.

The best of these “little symphonies” (and my favorite) is Symphonic Sketches. I have conducted the opening movement, “Jubilee,” many times and appreciate its exuberant and unbridled optimism. Its debt to Stephen Foster is evident in the warmhearted lyrical sections, which are especially evocative and beautiful.

Symphonic Sketches -1. Jubilee – Chadwick

Eastman-Rochester Orchestra conducted by Howard Hanson

Released on: 2004-01-01

Provided to YouTube by Universal Music Group

The 2nd movement of the work is “Noel,” which evokes the kind of Christmas scene one might find in a Currier and Ives print.

The 4th movement, “A Vagrom Ballad,” concerns hobo life and is the most obvious example of Chadwick’s homage to American music. It is filled with echoes of ragtime and music from burlesque halls and includes a parody of a solemn melody by J.S. Bach.

Today’s featured audio brings you the 3rd movement, “Hobgoblin,” as performed by the Durham Symphony Orchestra. Music historian John Tasker Howard beautifully captures the side of Chadwick we see in this movement: “Chadwick had a spark of genuine inspiration; he had a sense of humor. He made us chuckle, and he makes us think. And while we are thinking, he warms our emotions.”

In his lifetime, Chadwick was often called “the master of the scherzo”—the word scherzo (literally, “joke”) referring to a lighthearted and humorous work. A contemporary critic of Chadwick’s said of this quality in his music, “It positively winks at you.”

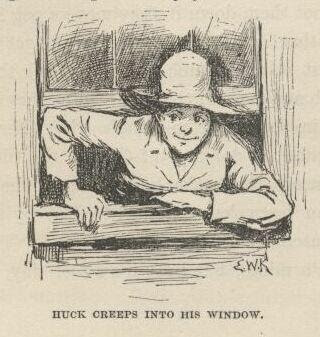

Chadwick himself called this movement a scherzo capriccioso (a capricious musical joke). It’s a witty miniature masterpiece that could have been named after one of Mark Twain’s young rascals, Huckleberry Finn or Tom Sawyer—headstrong American boys who upset people (and things) with mischievous behavior.

“The hobgoblin,” Chadwick explains, “is the rascally imp who frightens the maidens of the village, skims milk, mocks the breathless housewife at the churn, misleads night wanderers, and disconcerts the wisest aunt telling the saddest tale.”

Here, just in time for Halloween, is Chadwick’s musical trick-or-treat, “Hobgoblin”!

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Symphonic Sketches: III. Hobgoblin – George Whitefield Chadwick

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by William Henry Curry

Celebrating Maestro Curry’s 50 years conducting &

11 years with the Durham Symphony!

Enjoying the Music?

If you like what you’re seeing, please donate and let us know!

No matter the amount, we are grateful for your support and excited to bring you our music!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and a grant from the Triangle Community Foundation.