Monday Musicale with the Maestro – November 9, 2020 – In Search of the Great American Symphony, Part 3

Let Us Have Peace

Alan Hovhaness and his Symphony No. 2 (“Mysterious Mountain”)

In 1868, America was a divided land in chaos. The Civil War had ended only three years before. Four million African Americans had been emancipated in its aftermath. But 600,000 people had been killed in battle, the South’s major cities still lay in ruins, and the man who might have brought peace to this land with his credo of “malice toward none and charity for all” had been assassinated. The murderer’s initial plan had been a kidnapping, but he chose to kill instead after Lincoln suggested in his last speech that Blacks should be given the right to vote.

Lincoln’s assassination, then, was the earliest example of Black voter suppression.

Unfortunately for the Union and its newly liberated millions, Lincoln’s successor, Raleigh native Andrew Johnson, was not up to the challenge of healing the nation. He was an extremely stubborn and insecure man with Southern sympathies, and though he had promised an audience of Blacks a few years before that he would be their “new Moses,” he betrayed that promise at every turn. The so-called “Radical Republicans” were outraged when Johnson turned his back on Lincoln’s ideas of Reconstruction. The environment became poisonous, and Johnson was impeached. It was only a single vote in the Senate that spared him from being convicted and then removed from office.

After his impeachment, Johnson was regarded as “damaged goods,” and there was no way he could run again. (Donald Trump is the first U.S. President to run for office after being impeached.) So in 1868 the Republicans nominated the great Union general Ulysses S. Grant. This would appear to have been the most divisive choice imaginable, at least to the vanquished. Yet Grant’s integrity, his quiet dignity, and above all his campaign slogan (“Let us have peace”) was something the people needed and that Lincoln himself would surely have endorsed.

On March 4, 1861, Lincoln had delivered his first Inaugural Address in a moment when civil war was imminent. Several Southern states had already seceded from the union to form the Confederate States of America. Yet Lincoln had ended his speech with this eloquent plea for peace:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not be allowed to break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Let us have peace. . . .

On October 30, 2011 at the Carolina Theatre, the DSO performed a concert titled War and Peace. The “war” music included Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture and some intriguing selections by von Biber, Beethoven, and Mendelssohn which were discussed in our October 19th Monday Musicale. The “peace” part of the program was devoted to a single work, the Symphony No. 2 (“Mysterious Mountain”) by American composer Alan Hovhaness.

Alan Hovhaness was born on March 8, 1911 in Somerville, Massachusetts. During his teen years, he was attracted to Eastern philosophy and the mysticism of Catholicism. His own ancestry is part Armenian. And his music is a melting pot that reflects his love of Renaissance music, mid-20th-century Western music, and elements of Far Eastern music. But despite these myriad influences, he has a very personal “voice”.

Hovhaness explains,

My music is based on my inner experiences. I’ve always listened to my own voice. I was discontented with the music people said I should write—all clever and dissonant, intellectualized. Things that are very complicated tend to disappear and get lost. Simplicity is difficult, not easy. Beauty is often simple. All unnecessary elements are removed—only essence remains. I wanted to write music that was deeply felt, music that would move people. I believe in melody, and to create melody one must go within oneself. I admire the giant melody of the Himalayan mountains, seventh-century Armenian religious music, classical music of South India, orchestral music of Tang Dynasty China around 700 A.D., and the opera-oratorios of Handel.

Clearly he achieved his goal to move listeners with singable, lyrical, and melodic works. In his lifetime, he became one of the most beloved of 20th-Century American composers—a popularity with audiences that his composing contemporaries did not experience.

This should not be surprising, perhaps. For one thing, Hovhaness’ music bucks the trend in the second half of century, when “academics” and many practitioners of Western art insisted that melody (even tonality) was an outdated concept. Such arbiters of “quality” found acceptable influences only in the composers of the atonal 2nd Viennese School (e.g. Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern) and the Darmstadt School (Boulez, Stockhausen, and John Cage) and considered popularity to be PROOF of poor quality! As a student at the Oberlin Conservatory, I often heard this statement attributed to Schoenberg: “If it is good it is not popular, and if it is popular it is not good.” The saying I recall may be inexact—its origin possibly apocryphal. But it encapsulates the actual views of those schools rather neatly.It may be amusing to us today to consider the self-enclosed and self-serving nature of such pronouncements! But Hovhaness was not influenced and didn’t need the critical tide to turn: “My purpose,” he wrote, “is to create music not for snobs, but for all people—music which is beautiful and healing.”

Imbued with such confidence and joy in creating, Hovhaness was enormously prolific, with a catalogue of almost a thousand published and unpublished works. And I should note here that he’s in very good company since Bach, Mozart, and Schubert each wrote over a thousand pieces themselves while developing and polishing their craft. But this fact was a moot point to the “elites” of Hovhaness’ day, who had come to equate productivity with a lack of proper self-critical ability. Even in the late 19th century, romantic composers such as Bruckner, Mahler, and Ravel composed no more than 20 works each. Webern and Berg wrote far fewer (and were less popular, as I’ve noted). So prolific composers like Darius Milhaud, Heitor Villa-Lobos, and Hovhaness were never going to be taken seriously by the academics of their day.

A more useful observation might be that Hovhaness’ enormous output is daunting to analyze and evaluate. (He wrote more than 60 symphonies, for example!) And there is a point to made about the relative lack of variety in his materials. His East-meets-West tonal palette contains no more than 5 elements: melodies, repetitive ostinato, fugues, and music depicting the distant murmurs of people and Nature, evoking a sense of the sacred—even a spiritual gateway—in the natural world. But he manages these powerfully and with amazing facility. We hear driving rain and echoes resonating between mountain ranges (Symphony No. 2); the sounds of the sea shaped to cradle recordings of actual whale song (And God Created Great Whales); and the haunting legacy of 7th-century Armenian religious music (Prayer of St. Gregory). His music is not only accessible, but also perfect for those who have embraced World Music, New Age music, Transcendentalism and its variants.

Hovhaness died in the summer of 2000. That night, at a North Carolina Symphony concert, I paid tribute to his memory.

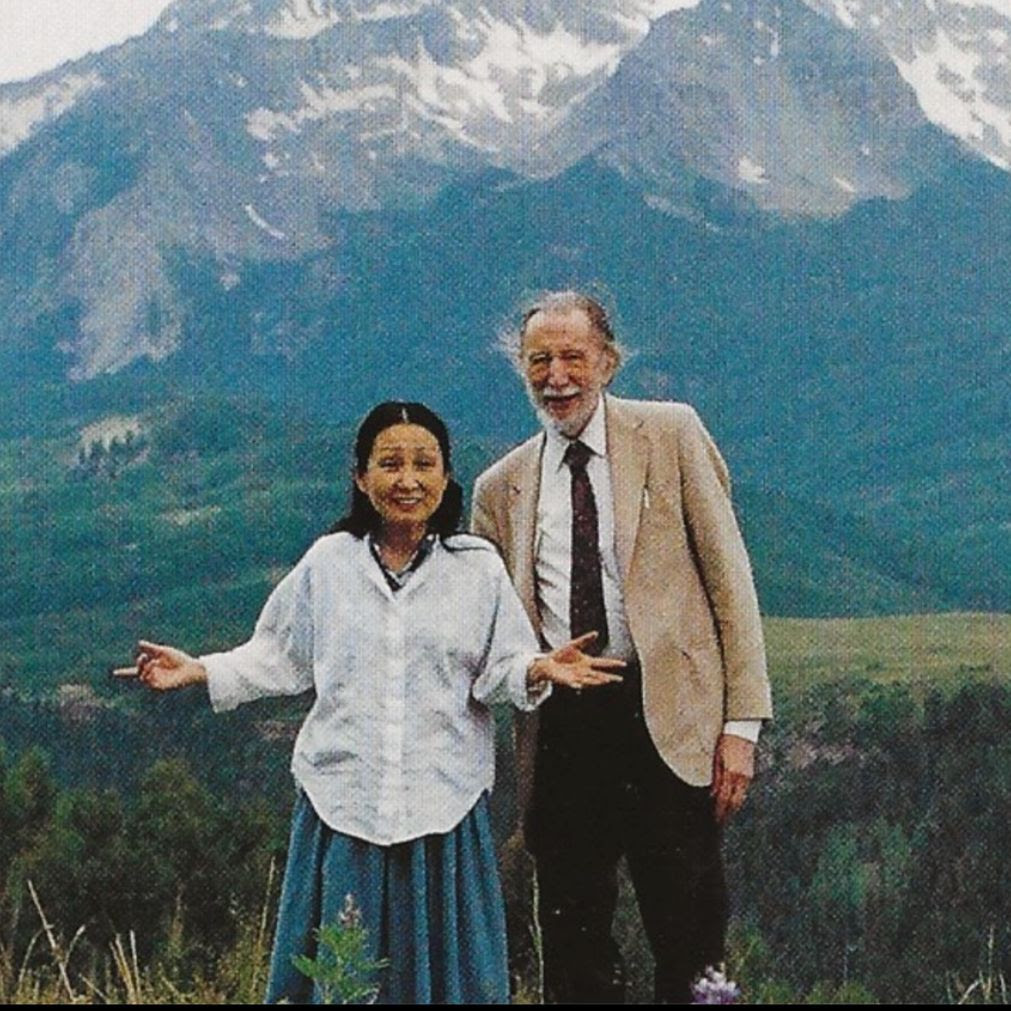

A friend of mine taped my comments, transcribed them, and sent them to his widow, soprano Hinako Fujihara Hovhaness. (She lived in Seattle for 20 years with her late husband and still makes her home there.) A few months later, I received a beautiful letter from her, containing these moving lines:

During our 24 years together, I watched Alan composing. He is without a doubt, the most prolific composer of the 20th century.. He did not follow the mainstream of contemporary music, but his own voice (his instinct) and the voice of a higher source. To me, he was music itself.

Hovhaness’ most famous piece—and a prime example of his meditative and ethereal style—is the Symphony No. 2 (“Mysterious Mountain”). Premiered in 1955 on an NBC telecast featuring the Houston Symphony Orchestra, the piece is dedicated to the legendary Leopold Stokowski, who conducted this first performance. Speaking of the symphony’s title and implicit mysticism, Hovhaness noted,

I love mountains very much. I used to climb them a great deal. I titled this work “Mysterious Mountain” for that mysterious feeling one has in the mountains—not for any special mountain, but for the whole IDEA of mountains, a universal mountain if you will. This could be about any mountain one loves. Mountains are symbols, like pyramids, of man’s attempt to know God. Mountains are symbolic meeting places between the mundane and spiritual worlds.

Hovhaness describes the first movement as “hymn-like and lyrical, using irregular metrical forms” Here is the DSO’s performance of this movement—an unending stream of serene melodies.

Symphony No. 2 (“Mysterious Mountain”):

I. Andante con moto – Hovhaness

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by William Henry Curry

The second movement, Hovhaness writes, is “a double fugue, developed in a slow vocal style. The rapid second subject is played by the strings, with its own counter-subject and with strict, four-voice canonic episodes and triple counterpoint episodes.”

Despite this complex and academic description, this movement is, for me, the most viscerally exciting I know of in his symphonies. After an opening consisting of sublimely peaceful music, he launches abruptly into a faster section as the strings race through exuberant and athletic passages. The writing here is at once powerful, delicate, and complex—overlapping at times, but with sections finishing at just slightly different moments to create the effect of an echo across majestic distances. Underneath, the woodwinds and brass seem to inhabit an entirely different temporal region with slow-moving religious chants. Amazing!

Symphony No. 2 (“Mysterious Mountain”):

II. Moderato maestoso, Allegro vivo – Hovhaness

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by William Henry Curry

The finales of most symphonies feature a dramatic conclusion, evoking an enormous spiritual challenge or victorious resolution. But the final movement of “Mysterious Mountain” is the calmest one in the symphony. “Like the first movement,” the composer writes,

this music is lyrical and hymn-like. A chant in 7/4 is played softly by muted French horns and trombones. A giant wave in a 13-beat meter rises to a climax and recedes…. A middle melody is played in a quintuple beat. Muted violins return with the earlier chant, which is gradually given to the full orchestra.

For me this movement evokes in sound the mystery of a vast and quiet cathedral—the quiet confidence and reverent contemplation the composer’s friends saw at the core of his being.

Symphony No. 2 (“Mysterious Mountain”):

III. Andante espressivo – Hovhaness

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by William Henry Curry

In a 1971 interview published in Ararat magazine, this deeply spiritual and optimistic artist seemed for the first time truly troubled about the future of America. “We are,” Hovhaness wrote,

in a very dangerous period. We are in danger of destroying ourselves, and I have a great fear about this. Physical science has given us more and more terrible deadly weapons, and the human spirit has been destroyed in so many cases. So what’s the use of having the most powerful country in the world if we have killed the soul? It’s of no use.

Though spoken almost half a century ago, his words are still relevant. We are in danger. Yet we are still here–despite the resurgent and inherent dangers of untrammeled capitalism and the dark, selfish side of humanity we are too quick to deny.

Friends, we must be friends. Let us take advantage of the “woke” future that is now in front of us to heed Lincoln’s “better angels of our nature” and finish the work begun in that long-ago dark time to heal our nation.

Let us have peace. . . .

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Celebrating Maestro Curry’s 50 years conducting &

11 years with the Durham Symphony!

Enjoying the Music?

If you like what you’re seeing, please donate and let us know!

No matter the amount, we are grateful for your support and excited to bring you our music!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and a grant from the Triangle Community Foundation.