Monday Musicale with the Maestro – November 23, 2020 – Journey Into Jazz, Part II: Duke Ellington and Martin Luther King

Journey Into Jazz, Part II: Duke Ellington and Martin Luther King

My Friends,

This has been a challenging year. The Latin phrase annus horribilis (“horrible year”) comes to mind. And yet, during this Thanksgiving week, I hope that you have—despite all—much to be thankful for. I am thankful that I am healthy and alive, as are all my close friends. And just before I sat down to write these words, I received the greatest Thanksgiving blessing of my life—a wonderful conversation with my exceptionally lively step-mother, Doris Evans Curry, who is now 106!

She was born on June 1, 1914. We talked about some of the remarkable challenges of her life, including the death of her two siblings, who perished during the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918-19. She has lived through the Great Depression, World War II, the Civil Rights era, the assassination of some of our great American leaders, and the death of two husbands. And she has endured all this while living in a country where an African American woman had to be constantly on guard to “keep the faith.”

After growing up in Pittsburgh, she graduated from the University of Pittsburgh in 1935 with a Bachelor’s degree in secondary education. Her dream was to be an English teacher, but then she hit the glass ceiling. She said, “I had hoped that things would change here, but at this time, ‘colored’ teachers were not accepted into the Pittsburgh Public Schools. I was told that if I wanted to teach, I would have to move to the South.” Instead, she took a job as a secretary to support herself and her younger brothers and sisters. In 1944, she became the first African American woman to be appointed a manager with the Pittsburgh Housing Authority. I asked her how she had managed to rise above the hurdles she had to face, and she said quite simply, “I just kept going.”

My mother, Florence Martha Hamilton Curry (“Kitty” to her friends), was my father’s second wife, and she was the greatest and most positive influence in my life. But she passed away in 1974 (at age 57), and in 1980, my father married Doris. I was thrilled that he had found a partner as brilliant and warm as my mother had been. So I would like to dedicate this blog to Doris Evans Curry, the magnificent lady who graced my father’s last eight years with her abundant love and care.

A King and a Duke

Like every African American family in the 1960s, the Curry home featured a framed picture of Martin Luther King, Jr. When we think of King and music we automatically think of gospel music, especially the “theme song” of the civil rights movement, “We Shall Overcome.” But less well known is that King was a great aficionado of jazz. On January 14, 2017, in honor of the Martin Luther King Holiday, the DSO played a special musical tribute to him at the Reynolds Theater, on the campus of Duke University. Also featured at this performance was the John Brown “Little” Big Band. John Brown is one of America’s masters of jazz bass. He has been the Director of Jazz studies at Duke University for several years, and this past June he was named as Duke’s first full-time Vice-Provost for the Arts. Our guest speaker for this performance was Keith Snipes, an actor and singer well known for his portrayals of African American icons such as Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King. In this concert, he intoned King’s remarkable message “On the Importance of Jazz,” written for the opening of the 1964 Berlin Jazz festival.

Here is Keith Snipes, with musical background provided by John Brown’s “Little” Big Band.

John Brown “Little” Big Band – Keith Snipes, speaker

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Maestro William Henry Curry, Music Director

Reynolds Industries Theater, Duke University, Durham, NC

Sounds of Justice & Inclusion – Honoring Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

January 14, 2017

Also on the program were several works by Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington. In a future blog I will delve deeper into Duke’s legacy. But in doing research for this concert, I found that Ellington had written at least two works in honor of Martin Luther King. One was a section from a large-scale composition for the theater titled My People. This work was written for Chicago’s Centennial Celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation—a six-week-long festival that was the only national celebration of that momentous occasion. In August 1963, President John Fitzgerald Kennedy wrote a brief message to the festival’s director, Alton A. Davis, to honor the event. “It comes,” he writes,

at a time when we are struggling to eliminate the last vestiges of racial discrimination. This important event signifies much more than the commemoration of the centennial anniversary of the emancipation from slavery in our great Nation. It will expose for all to see the significant contribution of the American Negro to the cultural, scientific, and political growth of the Nation at home and in the world in the past century. It will further interracial understanding and hasten the coming time of equal opportunity for all citizens.

Four months later he was cut down by an assassin in Dallas. And why was he in Texas? Earlier that year, in response to the horrifying racial unrest in Birmingham, on June 11, 1963, he had suddenly decided that he MUST address the nation, and that night he did—memorably—on live TV.

I was eight years old, and my family tuned in, of course. I still remember their stunned silence after the conclusion of his speech as we wondered, Did he really say THAT?! Did a white man say out loud that Blacks were being treated unjustly in this country? Did he really say that we should ALL be allowed to vote? Did he really say that Blacks should be able to eat in any restaurant they wanted and to stay in any hotel of their choice? I listened to the speech again before writing these words, and I still find Kennedy’s address to be the most forthright—indeed the most scathing—indictment of white supremacy that I have ever heard.

Here is an MSNBC documentary featuring Kennedy’s Civil Rights address to the nation that also explains its context.

Many white Southerners were outraged at Kennedy’s speech, and Vice-President Lyndon Baines Johnson felt that Kennedy had made a grievous error with those voters and might as a consequence lose the 1964 election to the likely Republican candidate, Barry Goldwater. So Johnson proposed that the president tour the South to do fund-raisers and calm conservatives, who were threatening to bolt from the Democratic party, put off by his progressive remarks. This was the reason Kennedy came to Dallas that fateful day—and the fact that this is so little known calls to mind Gore Vidal’s assessment of the U.S. as “The United States of Amnesia.”

Vice-President Johnson was a Southerner, and he knew all too well the need many white voters felt to pin their troubles on a scapegoat. As reported by the Washington Post, it was during this Southern tour that Johnson said to Bill Moyers (his aide), in a private conversation,

I’ll tell you what’s at the bottom of it. If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you are picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.

I mentioned in my November 9th blog that Lincoln was murdered (a change to the original plan for kidnapping) directly after calling for policies that allowed all Blacks to vote. And I called his killing an early effort to suppress Black voters. In much the same way, Kennedy was a victim of those who sought to suppress Black voters and oppose their civil rights.

Sad to say, the politics of divisiveness and resentment are still active as I write these words. And for Blacks in America, the struggle continues, even in the aftermath of the 2020 election.

During the civil rights era, Duke Ellington and his band played many benefits for groups like the NAACP, the Urban League, and the United Negro College Fund. The year 1963 had been a momentous one for events in the history of Black civil rights—most notably the March on Washington that included Martin Luther King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial. At the same time, Duke Ellington was writing a new work to celebrate the centennial of emancipation. It was intended for the Century of Negro Progress Exhibition, to be performed in the 5,000-seat Arie Crown Theatre at Chicago’s McCormick Place. It was a work titled My People, and indeed he described it as being “a swinging thing about my people.”

In his book Duke Ellington’s America, Harvey B. Cohen explains that Duke meant the work to have a populist appeal for adults and children (392). Ellington wanted to focus on “ ‘mainly Negro children who have not been taught Negro history’ ” (392). Cohen says,

Up to nine thousand spectators, including thousands of children, saw the show daily for six weeks. One of his band’s vocalists, Joya Sherrill, said “He felt like he was making a racial contribution.” A year later, he told Carter Harmann, “I enjoyed this as a challenge because I was the lyricist, the composer, the orchestrator, I directed it, I produced it, I lit the show, I did everything, and it was just a ball!” (392)

According to Cohen, Ellington’s son Mercer even helped paint the sets (392).

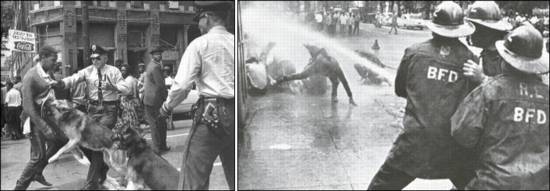

The work consists of over a dozen songs which were meant to reflect the African American experience over the 100 years since emancipation. One of the most powerful of the reflections is “King Fit the Battle of Alabam’,” a paraphrase of the song title “Joshua Fit [Fought] the Battle of Jericho.” In April of that year, a violent racial confrontation had occurred in Birmingham, Alabama between thousands of African American civil rights marchers (led by MLK) and the white protestors and police (led by the City’s Commissioner of public safety, Eugene “Bull” Connor).

The marchers were demanding the immediate integration of Birmingham’s department stores. The ensuing violent scenes that erupted were seen on live TV. Americans were horrified by the spectacle of dogs and high-pressure fire hoses turned on Black citizens. Cattle prods were used also, even on women and children.

Duke’s song, “King Fit the Battle of Alabam’ ” was his musical commentary on this scene. But it is not an oppressive statement. Rather, it strikes me as having a satirical edge. Ellington sang his song describing this “battle” at all the performances that summer.

ELLINGTON – Lyrics for “King Fit The Battle of Alabam’ “ from MY PEOPLE

King fit the battle of Alabam’ Birmingham,

Alabam’

King fit the battle of ‘Bam’

And the Bull (Sheriff “Bull” Connor) jumped nasty, ghastly, nasty.

Bull turned the hoses on the church people

Church people, ol’ church people.

Bull turned the water on the church people

And the water came splashing, dashing, crashing.

Freedom rider, ride,

Freedom rider, go to town,

Y’all and us gonna git on the bus.

Y’all aboard, sit down, sit tight, sit down!

Sit down, baby,

Sit down and sit tight,

Go to that school, don’t be no fool.

Sit down, be cool, be cool.

Little babies fit the battle of police dogs,

police dogs, police dogs,

Little babies fit the battle of police dogs,

And the dogs came growling, howling, growling.

The dog looked the baby square in the eye

And said, “Bye! Scram!”

The baby looked the dog right back in the eye,

And didn’t cry, and didn’t lam.

Now, when the dog saw the baby wasn’t afraid,

He pulled his Uncle Bull’s coat and said,

“That baby acts like he don’t give a damn.

“Are you sure we’re still in Alabam’?”

King fit the battle of Alabam’, Birmingham,

Alabam’,

King fit the battle of Birmingham,

‘Way down in Alabam’.

Unfortunately, there seems to be no recording of Duke himself singing. But here is a version for chorus arranged by Irving Bunton.

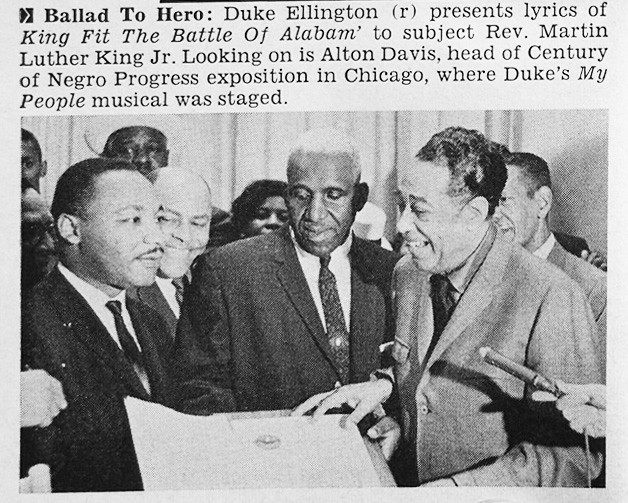

Martin Luther King attended part of the festival, and a first meeting between King and Ellington was arranged. King was honored and delighted by Duke’s production, especially the song memorializing his epic battle of Alabam’ in April of that year.

Here is an excerpt from an Ellington documentary. The woman speaking about King meeting Ellington is Marian Logan, wife of Ellington’s personal physician, Arthur Logan.

The final work Ellington dedicated to Martin Luther King—our featured DSO performance today—is the third movement from his orchestral work The Three Black Kings. The first movement is titled “King of the Magi,” referring to the biblical Black king who appeared at the manger of Jesus Christ. The second movement is titled “King Solomon.” The third, “Martin Luther King,” was written in the spring of 1974 when Ellington was in a hospital and seriously ill with lung cancer. Despite being kept in a hospital bed, he continued to compose and reflect on his life. What had begun as a eulogy for Martin Luther King turned out to be Ellington’s own requiem. A few days after completing it, his last composition, he died on May 24, 1974.

Though the work has a certain gravitas and poise, it is not funeral music. It is a swaggering and swinging piece of quiet dignity. And there is also, to me at least, a subtle sensual element in it. As Cohen explains, Duke’s granddaughter, Mercedes Ellington, was with him during those last weeks and recalls,

“I knew he must have been depressed at points or had bad moments I never knew. But I never saw that side even in the hospital. When I was with him in the hospital, I’d bring him pads and pencils and he’d love to talk about his great affairs, you know, the women in his life. I mean, a man’s dying in the hospital… and this is what he’s talking about!” (Duke Ellington’s America 574)

There is something delightfully resilient in that, though—Duke still thinking of the ladies as he “Takes the A Train” to Paradise! We hope you will enjoy the DSO’s performance of this final, joyous work of Duke Ellington, “Martin Luther King.”

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by Maestro William Henry Curry

Featuring: John Brown ‘Little’ Big Band

Sounds of Justice & Inclusion – Honoring Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Reynolds Industries Theater, Duke University, Durham, NC

January 14, 2017

Resilience is all in these times. As we approach Thanksgiving 2020, in this remarkably difficult year, it’s haunting to recall the official White House Thanksgiving of 1963. It was held early on November 18th (a Rose garden ceremony with the traditional pardoning of a turkey)—then 4 days later, Kennedy was gone.

The talk at the dinner tables was subdued. There seemed to be little to be thankful for in the wake of this terrible tragedy. America had lost its innocence, and indeed the rest of the decade was the most turbulent era of my life: the Vietnam War, the assassinations of Malcolm X, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther king.

This Thanksgiving will also feature a muted celebration with families unable to be together, divided over the issue of politics and the social distancing surrounding the reality of the pandemic. And yet, we are a resilient nation. And I do earnestly hope that, like me, you will be able to enjoy this holiday season as you try to be evermore positive, optimistic, and loving towards yourself and others.

The shortest inaugural address in U.S. history—and arguably, the most poignant—came from my favorite 20th-century American president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Its personal character makes it seem likely that he wrote it himself, and, for me, it expresses his personal fortitude and wise, hard-won optimism that I so much admire. We all can benefit this holiday season from this man’s hope and confident optimism about the future:

I remember that my old schoolmaster, Dr. Peabody, said in days that seemed to us then to be secure and untroubled: “Things in life will not always run smoothly. Sometimes we will be rising to the heights then all will seem to reverse itself and start downward. The great fact to remember is that the trend of civilization is forever upward; that a line drawn through the middle of the peaks and the valleys of the centuries always has an upward trend.”

So be safe, be well—be hopeful! And Happy Thanksgiving!

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Celebrating Maestro Curry’s 50 years conducting &

11 years with the Durham Symphony!

Enjoying the Music?

If you like what you’re seeing, please donate and let us know!

No matter the amount, we are grateful for your support and excited to bring you our music!!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and a grant from the Triangle Community Foundation.