Monday Musicale with the Maestro – January 25, 2021 – Grappling with Defeat: Nixon’s Dark Path to Grace and Dignity

In honor of the Presidential Inauguration this week, I would like to share with you an article I just contributed to cvnc.org to mark the occasion: “Persichetti-Lincoln-Nixon: A Study in Inaugural Politics.” https://cvnc.org/persichetti-lincoln-nixon-a-study-in-inaugural-politics/ This blog is meant as an addendum to that article, which explores a composition at the heart of a controversial incident involving President Richard Nixon. The controversy had nothing to do with the music itself, but instead with its historical text.

For Richard Nixon’s second inaugural celebration, the planning committee had commissioned a work by American composer Vincent Persichetti to be played at the Kennedy Center by the National Symphony Orchestra and conducted by Antal Dorati. The work Persichetti created, A Lincoln Address, featured a speaker and orchestra and utilized the text of Lincoln’s second inaugural speech. But as Persichetti was finishing the piece, the committee realized that certain phrases in the text would reflect poorly on Nixon’s role in the Vietnam War. When they removed the work from the inaugural program just days before the concert, replacing it with another American composition, a scandal erupted. As his aides were aware, Nixon’s character included a deep paranoia about the motives of those who opposed his politics. And it was perhaps the recognition of this dark side that led the 1973 inaugural committee to see Lincoln’s second inaugural address through Nixon’s suspicious eyes and to remove Persichetti’s entire piece from the performance. Nixon attended the amended concert—but we may never know for sure what part he played in the cancellation of A Lincoln Address.

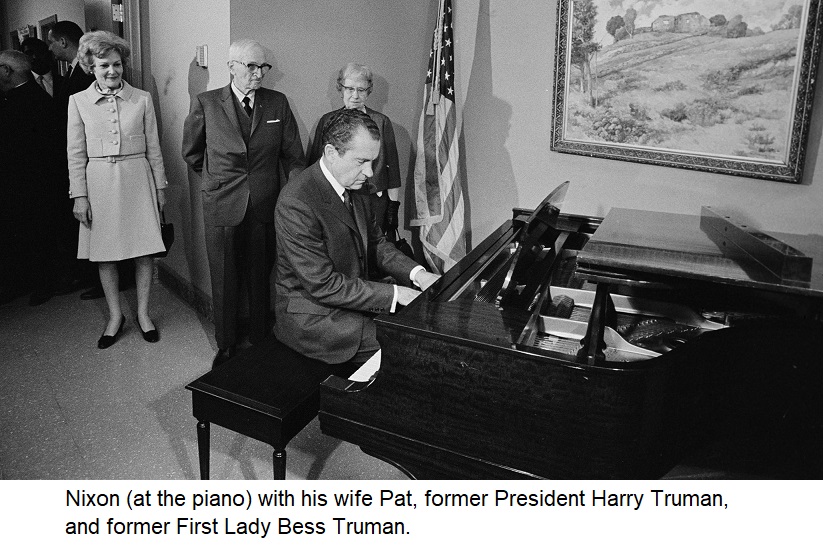

Nixon was a fan of classical music, and as president, he would occasionally request certain pieces to be played at the Kennedy Center concerts he attended. Three of these requested pieces were Liszt’s Les Preludes, Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, and Richard Rodgers’ music for the documentary Victory at Sea. This interest in symphonic music originated in his youth when he learned to play the violin. And before college he studied the piano, which he loved playing for the rest of his life.

The Kennedy Center is only a two-minute drive from the Watergate Complex, the “scene of the crime” that led to the discovery of other crimes committed by the Nixon administration. In 1974, the Watergate scandal, brought on by Nixon’s vengeful hatred for his enemies, reached its inevitable climax, and Nixon resigned the presidency before he could be impeached.

On August 8 of that year, he addressed America on a national TV broadcast to announce his decision to leave office the next day. He did not issue an apology for having directly damaged democracy and Americans’ faith in their government, but he did offer an “explanation”: “I would say only that if some of my judgments were wrong—and some were wrong—they were made in what I believed at the time to be the best interests of the nation.”

At 2 AM that night, he went to bed. He slept only four hours, the only sleep he had had in the last two days. Upon rising, he began taking notes about what he would say at a hastily organized farewell ceremony to the White House staff at 9:30 AM. The result was a speech that to me is as moving as both Lincoln’s second inaugural address and Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. It is a long, rambling, and sometimes maudlin speech, but unlike his “explanation,” it seems spoken from the heart and thoroughly sincere.

.

I would like to share with you my favorite passages from this sixteen-minute speech. The context is as important to remember as the speech itself, of course. Just two years before, Nixon had been re-elected with the greatest landslide in presidential history. But on this morning, Nixon had reached the nadir of his career and was suffering international humiliation. Like a Shakespearean tragic “hero,” Nixon was inexorably brought down by his character flaws, and he was betrayed by the inability (or refusal) of those who worked for him to act as a brake on his worst instincts. At this harrowing moment in his life, to quote a Paddy Chayefsky line from my favorite movie, Network, Nixon had simply “[run] out of bullshit.” His farewell remarks are mercifully devoid of “alternative facts” or “political spin.” This truly was Nixon’s moment of Truth, spoken from his “dark night of the soul,” but looking up and unexpectedly seeing a redemptive light. And with that bright epiphany, he found for himself a measure of hope, wisdom, dignity, and grace.

Nixon’s words were his attempt to heal himself, of course, and he nowhere quite admits the true (and all too common) source of his error: hubris and greed for power. But his emotional transparency here is striking and well worth recalling as a powerful sort of confession all its own. I find it infinitely moving that in his last moments as leader of our country, he chose to share his thoughts on finding a path to spiritual peace and moral strength at the limits of endurance. In doing so, he looked to one of his heroes, Theodore Roosevelt, as his model—and even quoted from Roosevelt’s diary.

At the age of 25, Roosevelt was the “golden boy” of New York politics. But in a single day, in the same house, Roosevelt lost both his mother and his wife, who died just after giving birth to a baby girl. On the morning Nixon gave his farewell speech, he decided to include with his remarks a poignant passage in the diary where Roosevelt mentions the loss of his wife:

“She was beautiful in face and form and lovelier still in spirit. As a flower she grew and as a fair young flower she died…. None ever knew her who did not love and revere her for her bright and sunny temper and her saintly unselfishness. . . When she had just become a mother, when her life seemed to be just begun and when the years seemed so bright for her, then by a strange and terrible fate death came to her. And when my heart’s dearest died, the light went from my life forever….”

Nixon continues:

That was TR in his twenties. He thought the light had gone from his life forever—but he went on. And he not only became President, but, as an ex-President, he served his country, always in the arena, tempestuous, strong, sometimes wrong, sometimes right, but he was a man. . .

And as I leave let me say, that is an example I think all of us should remember. We think when sometimes when things happen that don’t go the right way, we think that when you don’t pass the bar exam the first time. . . .We think that when someone dear to us dies, we think that when we lose an election, we think that when we suffer a defeat that all is ended. We think, as T.R. said, that the light had left his life forever. Not true.

It is only a beginning, always. The young must know it; the old must know it. It must always sustain us, because the greatness comes not when things go always good for you, but the greatness comes and you are really tested, when you take some knocks, some disappointments, when sadness comes, because only if you have been in the deepest valley can you ever know how magnificent it is to be on the highest mountain.

Always give your best, never get discouraged, never be petty; always remember, others may hate you, but those who hate you don’t win unless you hate them, and then. . .you destroy yourself.

And so, we leave with high hopes, in good spirit, and with deep humility, and with very much gratefulness in our hearts. I can only say to each and every one of you, we come from many faiths, we pray perhaps to different gods—but really the same God in a sense—but I want to say. . . not only will we always remember you, not only will we always be grateful to you, but always you will be in our hearts and you will be in our prayers.

Thank you very much.

–Richard Nixon. August 9, 1974

I believe that Richard Nixon’s heartfelt and eloquent remarks are especially meaningful for us during this era as we face the political upheavals, loss of loved ones, and occasionally the loss of our own faith and optimism.

In my life, I have seen many personal and national setbacks, all of which eventually led to a positive resolution when faced with honesty and courage. This is a great country, and we are a great people, and together—TOGETHER—we will be worthy of our ancestors.

At the January 1973 concert at the Kennedy Center that was to have included Persichetti’s A Lincoln Address, a magnificent work by Aaron Copland replaced it: Fanfare for the Common Man. Copland had had his own run-ins with politicians exactly twenty years before, when HIS setting of Lincoln’s words was pulled from a presidential inauguration! His Lincoln Portrait was to have been performed by the NSO at the celebrations for Republican President Dwight Eisenhower. But a few days before the performance, a Republican member of the House of Representatives accused Copland of having “suspect [left-wing] political affiliations.” The chairman of the inaugural committee immediately dropped Copland’s Lincoln Portrait from the program to avoid criticism from right-wing Republicans. (I will examine this issue more closely in a future blog.)

The title for Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man was inspired by a 1943 speech by vice-president Henry Wallace in which he said that the 20th century was to become “the Century of the Common Man” (The Century of the Common Man).

For my own part, I have always associated this piece with Lincoln’s egalitarian remark, “God must have loved the common man, he made so many of them.”

Fanfare for the Common Man – Copeland

Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by Antal Doráti

Released on: 1988-01-01

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Copy Editors: Marianne Ward and Tina Biello

Digital Layout and Publication: Tina Biello and Marianne Ward

Celebrating Maestro Curry’s 50 years conducting

& 11 years with the Durham Symphony!

“Monday Musicale with the Maestro” would not be possible without your support!

Thank you for being a important part of the Durham Symphony Orchestra family! We appreciate your sacrifice to help impact our community and wish you all the best in this New Year!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and a grant from the Triangle Community Foundation.

.