Monday Musicale with the Maestro – February 1, 2021 – Canceling Copland: Politics and Censorship in the Cold War Era

Canceling Copland: Politics and Censorship in the Cold War Era

When I discovered classical music in my early teens, my two American heroes were Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein—two iconic composers whose work is justifiably famous in the U.S. (and worldwide) for its profoundly American character and subject matter. I never worked with Bernstein, but I did have a wonderful experience with Aaron Copland in the late 1970s when I was Resident Conductor of the Baltimore Symphony. While delving into the subject of censorship in American culture in recent weeks, I’ve been struck by the irony that this warm, generous, and brilliant composer of works such as Appalachian Spring and Lincoln Portrait was briefly a victim of anti-communist hysteria (as was Bernstein) at the height of the Cold War.

In our current political climate, amidst talk of “cancel culture” and “culture wars,” it may be useful to remember that Copland’s works were once branded as somehow “un-American” and were banned from performance by several major symphony orchestras and university orchestras. The insanity of this may be difficult to believe today, yet it happened, and may be a cautionary tale for our times.

I met Copland when he served as guest conductor of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra for a week and I was his cover conductor (understudy). After the last rehearsal, I went to his dressing room, and we had a long chat. I will save the details of our conversation for a future blog about his influence on me as a composer. But for me, his most compelling statement that day was that “The piece should seem to be composing ITSELF.” I understood that to mean that the music should be organic, straightforward, and direct.

Copland was a plain-spoken man, and his music is similarly without decoration or unnecessary complexity. Two of my other musical heroes, Beethoven and Handel, also find enormous strength in this way. Think of the direct, aggressive, in-your-face opening of the “Hallelujah Chorus” or of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. And whenever I compose, I am always thinking of Copland’s austere but granitic sincerity—and yes, simplicity.

Copland’s temperament was legendarily mature and accepting of the human condition, a fact that no doubt served him well. It was not until several years after our meeting that I learned about some of the complexities in his private life, including his being gay and “in the closet” his entire life. Added to this was the very public assault on his artistic life at the height of the cold war—the difficulty I alluded to earlier.

Author Lillian Hellman called the 1950’s “scoundrel time,” referring to the demagogues who gained notoriety during the Cold War by exaggerating, misrepresenting facts, and out-and-out lying about the all-but-non-existent threat of communism in America. Fear is a potent weapon, and many politicians manipulate fear to gain attention and accumulate political power. The worst of the American demagogues in 1950s America was Joseph McCarthy, a Republican senator from Wisconsin. During this period, he and many others turned America and its ideals upside down in search of card-carrying communists. Since there weren’t enough American communists to shake a stick at, these demagogues then had to invent communist menaces.

Their key tactic was to go after “left-leaning liberals,” who were vulnerable. During the 1930s—the height of the Great Depression—many people (including many East Coast artists) had experienced a passing interest or attraction to the Communist Party. In those difficult times, the notion of “sharing the wealth” had a great deal of appeal (as it does to some during our current economic crisis). People lent their names to petitions and donated money to causes that seemed ordinary then, but were considered “subversive” 15 years later, after the Cold War had begun. For many, interest in the Communist Party had ceased before the end of WW II. But the signed petitions and records of donations remained—a ticking time bomb waiting to go off.

For Copland, the explosion occurred in April 1949, when he picked up a Life magazine and saw his name on a list of 50 Americans described as “Communist dupes and soft-headed do-gooders.” This list included Leonard Bernstein, Charlie Chaplin, Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann (Death in Venice, Dr. Faustus), playwright Arthur Miller (Death of a Salesman, The Crucible) and Harvard professor F.O. Matthiessen. Life was the most famous magazine in America at the time—a credible and trusted publication, not a National Enquirer sort of rag. So, its public chastisement of these individuals was no joke. In the wake of this article, the accused often received hate mail and obscene phone calls. Friendships and marriages were destroyed. Careers were ruined. Reputations were soiled. A person could be the victim of public boycotts, deportations, and jail sentences—and the emotional distress was extreme. Professor F.O. Matthiessen committed suicide.

Luckily for Copland, the article did not cause such an immediate stir in his private or professional life, and for a time all went forward as usual. Yet despite his reserve, friends noted that the experience was truly harrowing for him. And within a few years, the repercussions were clear.

As I mentioned last week, Copland’s work Lincoln Portrait had been programmed for the January 1953 inauguration of Republican President Dwight Eisenhower and was to have been performed by the National Symphony. But mere days before the performance of this work, Republican Representative Fred Busby of Illinois vigorously protested the use of music by Copland, citing what he felt were Copland’s “suspect political affiliations.” The chairman of the inauguration arrangements committee immediately dropped the piece from the program saying only, “We don’t want to do anything that would bring criticism.”

The reaction of the Arts community was heavily pro-Copland. That very day, the League of Composers sent a telegram to the inaugural committee saying, “We urge you to reconsider your action and to restore to the program a composition recognized everywhere as being great American music by a great American composer.”

Copland then released a statement to newspapers and radio stations.

“This is the first time, as far as I know, that a composition has been publicly removed from a concert program in the United States because of the alleged affiliations of the composer. I would have to be a man of stone not to have deeply resented both the public announcement of the removal and the reasons given for it. No one has ever before questioned my patriotism. . . I have admitted sponsoring causes which seemed to me to have merit, but I never lent my name to any organization except as a loyal and liberal American. In a Brooklyn public school, I was taught to believe that an American took pride in his right to speak his mind on controversial subjects and to protest when some action seemed unworthy of our great democratic traditions….

Having been encouraged to speak openly as an American citizen, it now appears that I am in danger of being penalized for so doing. My ‘politics’ (tainted or untainted) are certain to die with me, but my music, I am foolish enough to imagine, might just possibly outlive the strictures of a member of the Republican party.”

(Aaron Copland and Vivian Perlis, Copland Since 1943, 186)

Copland also sent a version of the letter directly to Eisenhower.

Of course, Busby fired back, saying (among other things) that Copland’s music perhaps should be banned from performances of American military bands and orchestras overseas. As Copland biographer Howard Pollock reports, Paul Hume of the Washington Post replied that “ ‘Every American musician and music lover has a vital concern in this matter. It was through such machinery as the Congressman advocates that the music of Mendelssohn [a Jew] was banned in Nazi Germany. Can it happen here?’ ” (Aaron Copland 453)

Yes, it could—and did. In April 1953, McCarthy achieved part of his goal when he successfully lobbied the State Department to blacklist music and recordings by Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and others from American libraries sponsored by our government overseas. Copland’s passport was also revoked. Some years later, after the ignominious downfall of McCarthy, Copland’s passport was re-instated and the ban on these composers’ works was ended. But censorship for questionable political motives has remained an ongoing problem. As late as 1967, several conservative groups and newspapers were STILL protesting Copland’s appearances as a conductor and lecturer!

In 1977, I had to deal with my own unexpected “controversy” over Copland’s Lincoln Portrait, which I’d planned to program on my youth concerts with the Richmond Symphony Orchestra. This work, as I explained in last week’s blog, features a speaker and orchestra in a musical setting of text by Abraham Lincoln. I was told by an executive there that I was “crazy” for wanting to perform this work—in the capitol of the Confederacy! I was astonished, and I protested, but that was a battle I lost. Because of several additional incidents like that, I was happy to accept a post as Resident Conductor with the Baltimore Symphony several months later.

Even Copland’s ballet Appalachian Spring—winner of a 1945 Pulitzer Prize—suffered a sharp decline in number of performances during the 1950s, because of his political views. It seems incomprehensible that such a warm, American-sounding piece could have political problems. But in our current era of rethinking cultural artifacts and the character of those who created them, we should consider our history and act wisely in terms of what to cancel and what to keep. How will history regard our choices? And how will we later regard ourselves? Some mistakes are unavoidable. But we should hope to avoid the more ridiculous mistakes of our predecessors.

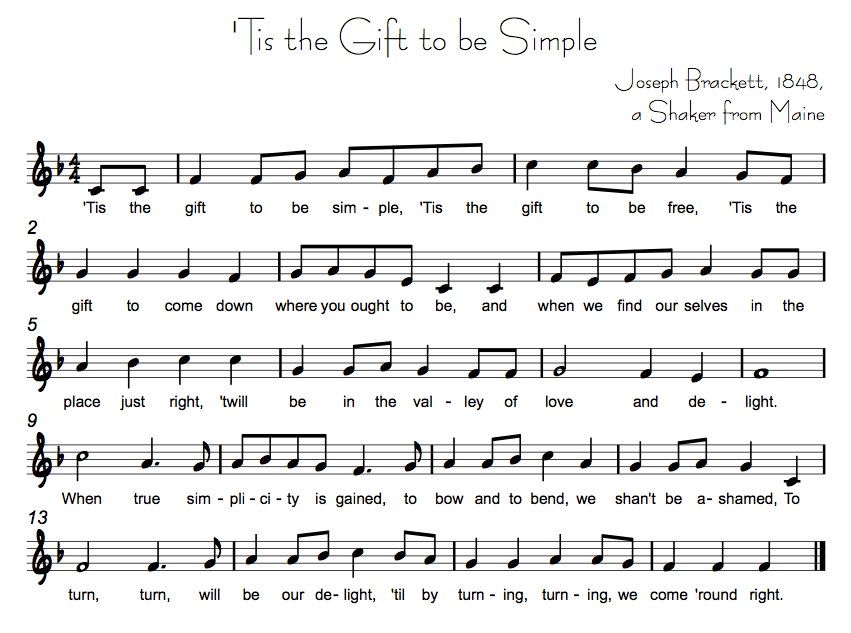

The most famous section of Copland’s ballet uses a song, Simple Gifts, originating from the Shakers, a Christian sect related to the Quakers. The name derives from that group’s ecstatic, “shaking” movements during religious services.

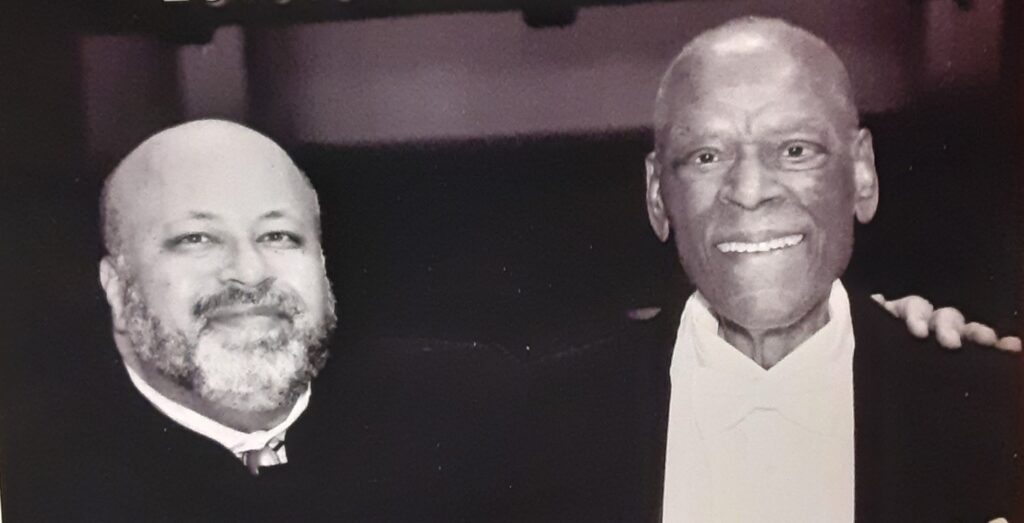

Here is a version for voice and piano, with Copland at the piano and William Warfield as the speaker. (William Warfield was the speaker in the North Carolina Symphony’s performances of my MLK piece Eulogy for a Dream.)

Fanfare for the Common Man – Copland

Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by Antal Doráti

Released on: 1988-01-01

On April 2, 2016, at the Carolina Theatre, the DSO and I performed Copland’s Variations on the Shaker Hymn “Simple Gifts” from Appalachian Spring. I find this music to be deeply moving. Copland’s spare style has been inspirational to me as a composer in my attempt to write music that is fresh, pure, and based on the principle that less is more.

Variations on a Shaker Song (Appalachian Spring) – Aaron Copland

Durham Symphony Orchestra

William Henry Curry, conductor

NC Music & All That Jazz

The Carolina Theatre

Durham, NC 4/2/16

This American-sounding music is an essential part of our culture. Copland’s most popular pieces are those that conjure vivid musical images of our rural roots and the West. Pieces like the ballets Appalachian Spring, Rodeo, and Billy the Kid bind us together as a nation in what Lincoln called “the mystic chords of memory”. And I have always felt, when performing his Lincoln Portrait, that I’m conducting a noble “collaboration” created by two of my greatest heroes. This is my favorite American work. And here is a link to a recording of it, the words magnificently intoned by Charlton Heston.

Copland: Lincoln Portrait

A Lincoln Portrait – Aaron Copland

Utah Symphony Orchestra

Maurice Abravanel, conductor

Charlton Heston, narrator

Big Americana Box on The Bach Guild

But in this era of “cancel culture” will this piece be removed from concerts? Certainly not for Copland’s being gay or a “lefty”, but perhaps one day because of the comments Lincoln made elsewhere that may seem jarring to some—including this one from the first Lincoln/Douglas debate on September 18, 1858: “I am not, nor have ever been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races. . .nor of qualifying them [Blacks] to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people.”

But as is always the case, context is important. Lincoln was running to be the senator from a mostly rural “western” state. IF he said anything contrary to those comments, his political career would have been finished, and he never would have become our greatest President and ultimately, “The Great Emancipator.” For hundreds of reasons, Lincoln is the human being I most admire in world history. And because as president he freed my ancestors (only 50 years before my father was born), I couldn’t care less about what he HAD to say to get elected.

As we make decisions during this decade, let’s remember the lessons of our history: “purity tests” are doomed to be unending and self-defeating. We are all “children of our time,” and we should be careful in judging those who lived in a different era, under different circumstances.

In closing, I would like to offer you this thought as a “simple gift”: It is futile to negatively judge the dead; instead, we should try to learn from their mistakes.

Can I get an Amen on that?!

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Copy Editors: Marianne Ward and Tina Biello

Digital Layout and Publication: Tina Biello and Marianne Ward

Recording Engineer: Mark Manring https://www.manring.net/

Celebrating Maestro Curry’s 50 years conducting

& 11 years with the Durham Symphony!

“Monday Musicale with the Maestro” would not be possible without your support!

Thank you for being a important part of the Durham Symphony Orchestra family!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and a grant from the Triangle Community Foundation.

.