Monday Musicale with the Maestro – February 22, 2021 – Mardi Gras 2006: The Eternal Spirit of Mardi Gras

I have always felt a deep connection to the buoyant spirit of New Orleans. From 1990 to 1996, I lived there, and from my first day in “The Big Easy,” I wanted to write a musical act of homage to the city. That opportunity arose twenty years ago, when I was commissioned to write a cello concerto for the magnificent Bonnie Thron, principal cellist of the North Carolina Symphony. The piece was to be subtitled “The Garden District,” the name of the beautiful area in which I lived. It is aptly named! Plants and flowers abound, and at night the air is thick with fragrance. Unhappily, this piece was not finished for a variety of reasons, including compositional challenges posed by writing a virtuosic vehicle for solo cello and large orchestra. Given its range, the cello would have been too easily drowned out by the kind of large-scale orchestra I’d envisioned, so the project stalled. But my dream to write a work honoring my favorite city in the world did not die. And my plan for what kind of piece it should be was changed by a natural disaster—the devastation of Hurricane Katrina.

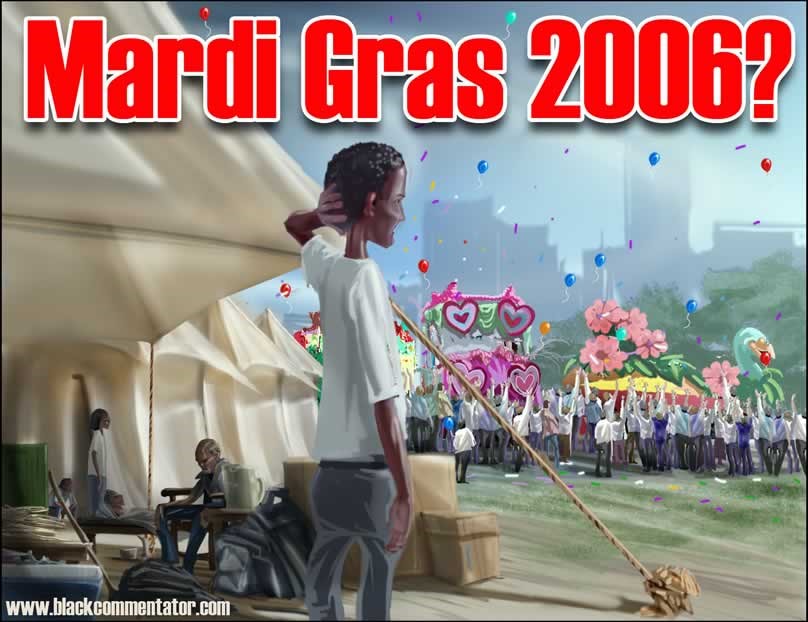

It goes without saying what my reaction was during the last days of August 2005 as Hurricane Katrina devastated my soulmate city. In the aftermath of this catastrophe, as the city’s remaining inhabitants revealed their courage and strength, discussions about recovery came to revolve around the upcoming 150th anniversary of Mardi Gras in February 2006. Many thought the holiday should be cancelled out of respect for the dead and the displaced. But to the vast majority of the residents, a cancellation of Mardi Gras was unthinkable, tantamount to cancelling Christmas. As one native put it, “We need Mardi Gras for US! To heal US!” That opinion held sway.

In the spring of 2009, I visited New Orleans for the first time since the disaster. I was elated, of course, by what had survived—and crushed by what had not. Most sobering of all was my tour of the Ninth Ward, where I saw ruined homes still painted with numbers indicating how many bodies rescuers had found there. These images moved me to write a song honoring those who made it through this cataclysm and the many who did not. This work is dedicated to them both.

The form and philosophical content of the piece originates from my memories of the jazz funerals I often saw in New Orleans. On such occasions, the band plays a mournful dirge that is then followed—vanquished—by truly jubilant and life-embracing music.

The most memorable jazz funeral I witnessed was the one that honored legendary New Orleans jazz artist Danny Barker. I had not heard of Danny before his death, but the obituary notices greatly moved me, describing his decades of service to the local musical community. In the 1950s, when it seemed that the city’s unique tradition of jazz brass bands would die, Danny took it upon himself to interest the younger generation in the glory of this music. He went to schools, he taught on street corners, and he raised money for children to have instruments. The result was gradual but impressive: within several years, the city was once more alive with the sounds of its people’s glorious and unique form of music.

When I read about Danny’s achievement, I was at a low ebb in my life. I had reached my early 40s without really considering what my legacy as a musician and a person should be. But I realized that I had found a role model in Danny Barker, and out of respect to him, I attended his jazz funeral on March 17, 1994. I was keeping a journal at the time, and my notes record the presence of a large crowd and a 30-piece band.

It was anything but a solemn affair! Several vendors were selling beer, and it seemed to me that the musicians were imbibing more than anyone else. When the casket came out of the church, the band and I gathered around it while they played one final song for Danny Barker. As the hearse was “cut loose” for its final journey to nearby St. Louis Cemetery, the sun (as if on cue) burst forth and brightened the overcast scene. And as in all jazz funerals, the band began to play the most boisterous music imaginable as the casket vanished in the distance. People were dancing, swaying underneath giant umbrellas, and allowing the effects of the beer-drinking to be openly expressed. Let Joy be unconfined! But I would not have described this scene as having a carnival atmosphere. There was nothing blasphemous about the tone or the activities. Rather it seemed to be a respectful celebration of the precious gift called Life. All followed behind the band until they marched into the Second Line Bar and Lounge, where they continued to play!

This mix of the solemn and the burlesque, the sacred and the profane, made a deep impression on me, inspiring both the mood and structure of Mardi Gras 2006. With those memories as a model, my piece could have been subtitled “Requiem and Revival for New Orleans.” It is a tribute to that gritty, life-embracing spirit at the core of all those who endure tough times, rely on their faith, and go on to better days.

Much of the melodic material in this work consists of variations on the city’s theme song “When the Saints Go Marching In,” an uplifting song that describes the exhilaration of the coming Judgment Day. Every time I have gone to the French Quarter, I have heard one or more bands playing this melody. No one ever gets tired of hearing it! The melody’s permanent status as a classic led me to analyze it the way I would any classical piece by Bach, Brahms, Webern, etc. to discover its secrets. Much to my surprise, I found out that pitch-wise it truly is primitive. There are only 5 different notes in this melody, while the average folk or pop song has 7-12 different notes! Yet the tune does have a strong melodic profile. Its phrases neatly balance each other, and its repetitive nature makes it highly memorable. But truth to tell, none of these virtues are enough to explain its considerable magic and eternal appeal. Like all the great music I love, its power goes beyond logic and the rational.

Mardi Gras 2006

My piece takes place on February 28, 2006, Mardi Gras day. It is dawn. Upon waking, thoughts turn to the much-anticipated excitement of the day. However, thoughts darken as the recollection of past co-celebrants, now dead or relocated, obliterate all positive feelings. The song opens with a threnody for the dead. Before composing this, I knew I had to dig deep within myself to find the appropriate music, and it is this section that echoes the jazz funerals I have heard.

But then a different kind of music comes towards us from the distance—the sounds of a Dixieland Jazz band parading down the street, shakin’ the blues away. Out of bed…time to hit the streets! The soprano sings my song “I Survived,” a tribute to that devil-may-care spirit of New Orleans exemplified by one of its mottos: “Laissez les bon temps rouler.” (“Let the good times roll.”)

Next, we hear a musical phrase based on the main melody of my Christmas carol, “Snow Is Falling Here,” but given a Latin beat. This is a gesture to the many Latinos who came to the city in the aftermath of Katrina, bringing with them their own musical traditions.

This is followed by a majestic “swing” version of my “Hymn to Brotherhood” from The Kwanzaa Song (featured in our Musicale from December 28, 2020). This section includes the bracing sound of a brass band. And of course, no piece about New Orleans would be complete without a musical tip-of-the-hat towards its greatest native son, Louis Armstrong. For me, he is next to Mozart as the greatest apostle of musical joy. My tribute to him is a short section modeled on the sound of a remarkable band he played in—Joe “King” Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band.

After this, the singer returns to “I Survived,” and the accompaniment evokes Scott Joplin’s piano-based ragtime music, which led to the birth of jazz in New Orleans. The lyrics in this section refer to the well-known (and somewhat risqué) ritual of throwing beads from parade floats to the crowd below. Though the beads are dime-store quality, the crowd is carried away in the heat of the moment, yelling and reaching to get them as if they were the finest pearls. Some women, of course, have been known to partially disrobe to entice a “throw” in their direction—a detail of the holiday that I was loath to exclude!

As the lyrics get progressively more salacious, the strutting and swaggering are interrupted by raucous and discordant sounds from the first marching bands and giant floats of the day. In my sketches, I call this the “Edwin Edwards High School Band March.” This is a private joke, as there is no such school. Edwin Edwards was the winner of the Louisiana gubernatorial race in 1994, when his opponent was David Duke (a former member of both the Klan and the American Nazi party). I was living in New Orleans at the time and was dismayed at the prospects and the fact that Duke (though the loser) got 56% of the white vote there. Edwards was no saint himself, a rascally Bayou politician with more charm than integrity, as both his supporters and his enemies knew. But the choice was clear, and I remember seeing a bumper sticker during this election that said, “Vote for the crook, it’s important.”

We follow the floats and the bands down to the French Quarter and eventually wind up on Bourbon Street. It is here that we see the folks that are the most outrageously garbed and the most inebriated. To describe the drunks and the zanies, I have transformed the march into a tipsy, wobbly, and badly out-of-tune waltz. The sounds of the bands on Canal Street disrupt this, and we hear another variation of the waltz—a song describing an ornately costumed drag queen named Ko-Ko. (It IS Mardi Gras, after all.) Her garb and dreadful singing are described in detail by the soprano—mercifully interrupted by competing sounds from the band.

But as the festivities reach their orgiastic climax, the singer’s thoughts turn once more to those who shared in the bacchanale last year but perished during the Katrina disaster and have gone to that “new and sunlit shore.” The blues return, and the soprano sings folk lyrics associated with “The Saints Go Marching In.” We hear ghostly fragments of all the principal themes while the singer muses on the fragility of human life and the promise of a golden hereafter when we are to be reunited with our loved ones. The somber mood deepens as the opening dirge music returns.

All motion ceases and time stands still. A quiet, reflective moment follows, combining the main musical themes from the piece. A solo flute plays the “Hymn to Brotherhood” from The Kwanzaa Song which causes the gloomy clouds to dissipate. We hear a faint fragment of “The Saints,” as if from within the recesses of distant memory, and this internal vision produces a catharsis. This familiar melody, with its message of hope amidst the upheavals of Judgment Day, becomes louder and stronger, flooding the scene with spiritual sunshine as Katrina’s saints and survivors go marching into New Orleans. The final lyrics could be the credo of every died-in-the-wool New Orleanian: “Though the Big Easy’s not so easy, it suits me fine. It’s red beans and rice, it’s naughty and nice. Yes, my city of dreams. Oh, I will never leave New Orleans.”

Mardi Gras 2006, Lyrics and Structure

Requiem

Oh, when the sun refuse to shine

And when the moon turns red with blood

Lord, I want to be in that number

When the trumpet sounds its call.

“I Survived”

When the hurricanes come, I survive.

I just stock up on rum and survive.

With my rum and coke and my dreams up in smoke,

I party. You right; I’m alive.

When my lovers have flown, I survive.

And I’m so, so alone, I survive.

I just call up Ray and right soon he’s on his way

And laissez les bon temps rouler!

Oh, the men on the float leered at me.

Yes, my costume is tight, nothing fits.

And I got these beads by me showin’ them these:

My …….!

Mardi Gras March and Valse de Ko-Ko

Ko-Ko the drag queen is keeping it “real”

With fake fur and high heels.

When he/she sings, it’s: (Cadenza)

Fabulous!

So, let’s give her a hand

Oh, look out, here comes the band!

Remembrance

We’re on our way

To those who’ve gone before

And we all will be united,

On a new and sunlit shore.

Some say this world

Is all we’ll ever need,

But I’m waiting for that morning

When the new world is revealed.

Revival: “When the Saints Go Marching In” / “I Survived”

Oh, when the saints go marching in,

Oh, when the saints go marching in,

Lord I want to be in that number

When the saints go marching in.

And when the sun begins to shine

Oh, when the sun begins to shine

How I want to be in that number

When the sun begins to shine.

With the Lord up above, I survive.

With a heart filled with love, I survive.

And though the Big Easy’s not so easy,

It suits me fine:

It’s red beans and rice.

It’s naughty and nice.

Yes, my city of dreams.

Oh, I never will leave New Orleans!

William Henry Curry, music, lyrics and conductor

Shana Blake Hill, soloist

The featured soprano here is Shana Blake Hill, who was soloist for my first Durham Symphony Orchestra concert, the year before my appointment as Music Director in 2009. She is a brilliant singer—and under her married name (Blake Hill-Saya), a superb writer, too. She authors a weekly blog for the Festival Opera, and her biography of Aaron McDuffie Moore (one of the three founders of Durham’s Black Wall Street) was published last year by UNC-Chapel Hill Press!

You may read her full bio here:

Shana Blake Hill, Soprano » Biography

Mardi Gras 2020

Mardi Gras 2020 was on February 25, 2020, and it was, as usual, a jubilant, jam-packed, “let-the- good-times-roll” event. But the thousands of revelers crowded together made for a perfect viral incubator—a super-spreader event that put Louisiana at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic for weeks.

Mardi Gras 2021

With that in mind, there was no possibility of having a traditional Mardi Gras in 2021. But I know my soulmate city and its inhabitants, and I knew that there would surely be some kind of Mardi Gras. Period! And there was.

Last Tuesday, February 16, was one of the few times in the history of the 165-year celebration where there were no parades, floats, or bands. All the bars and restaurants in my beloved French Quarter were closed. That night, on YouTube, I watched several “streaming” street cams that were stationed on Bourbon Street—ground zero for merriment and mayhem on Mardi Gras night. But this time it was empty, a ghost street. This infinitely sad scene led me to remember my dearest friends who lived and loved this celebration alongside me. Friends who have since gone to that “new and sunlit shore.” And I wept.

But the next morning—revival! The internet was flooded with pictures of what people had done to celebrate without leaving their homes, turning porches and even whole houses into Mardi Gras floats!

The great Danish composer Carl Nielsen said that the theme of his 4th Symphony was “Music, like life, is inextinguishable.”

I approve that message.

The indomitable Spirit of Man is stronger than any cataclysm. And after a life-changing 2019 devoted to recovery from injury, surgery, and rehab, I’ve experienced this myself. Like my beloved New Orleans, I was able to build back better, finding renewed health and vigor–and deep gratitude for what persists and will flourish going forward. Since then my motto has been, If I am not in pain and no one I know is sick or dying, then this day is the greatest day that ever was. Rejoice! And let the revels continue!

There will always be a Mardi Gras.

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Copy Editor: Tina Biello

Digital Layout and Publication: Tina Biello

Video Mixing & Mastering: Max Wang

Celebrating Maestro Curry’s 50 years conducting & 11 years with the Durham Symphony!

“Monday Musicale with the Maestro”

would not be possible without your support!

Thank you for being a important part of the

Durham Symphony Orchestra family!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and a grant from the Triangle Community Foundation.