Monday Musicale with the Maestro – March 15, 2021 – A Musician’s Life with Brahms and His Symphony No. 4

The music of Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) has played an important part in my career as both a conductor and a composer. Brahms’ Tragic Overture was the first piece I chose to conduct with the Oberlin Conservatory Orchestra in 1974, when I was a student there. While I was studying that piece, my conducting teacher, Robert Baustian, made me realize that, while it is an extremely dramatic and emotional work, it is also as organic as a tree and as faultlessly constructed as a Swiss watch. Brahms has often been described as a “classical” Romantic period composer—in contrast to Mozart, who could be called a “romantic” Classical composer. I’m reminded of what the great conductor George Szell said about conducting and composing: “You have to think with your heart and feel with your brain.” From this revelation 47 years ago, and inspired by Brahms, I have endeavored in everything I have composed to write music that is deeply expressive and intellectually sound in construction.

Since that performance of the Tragic Overture, I’ve conducted all of Brahms’ major orchestral works. The 1st Symphony was featured on my Carnegie Hall debut and received a glowing review in the New York Times. However, my first performance of the 2nd Symphony when I was 24 garnered my first bad (though justly earned) review! And my first performance of the 3rd Symphony a year later was also not satisfying. Discouraged, I confessed my unhappiness about my inability to understand these works to the late Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, a wonderful conductor who was mentoring me at the time. He wisely told me that it is almost impossible to conduct a Brahms symphony well the first time. That’s because his works are “hard nuts to crack,” more inscrutable than the music of Tchaikovsky, which wears its heart on its sleeves.

I will always be grateful to Maestro Skrowaczewski for taking the time to help me when I was at a vulnerable moment in my career as a conductor. Any young person who is contemplating a career needs encouragement from a professional in the field they are interested in. It is one thing for our parents or our friends to tell us we can “make it,” but it is another thing entirely to receive encouragement from a mentor—a guide who can share inside information that only a pro in that field would know.

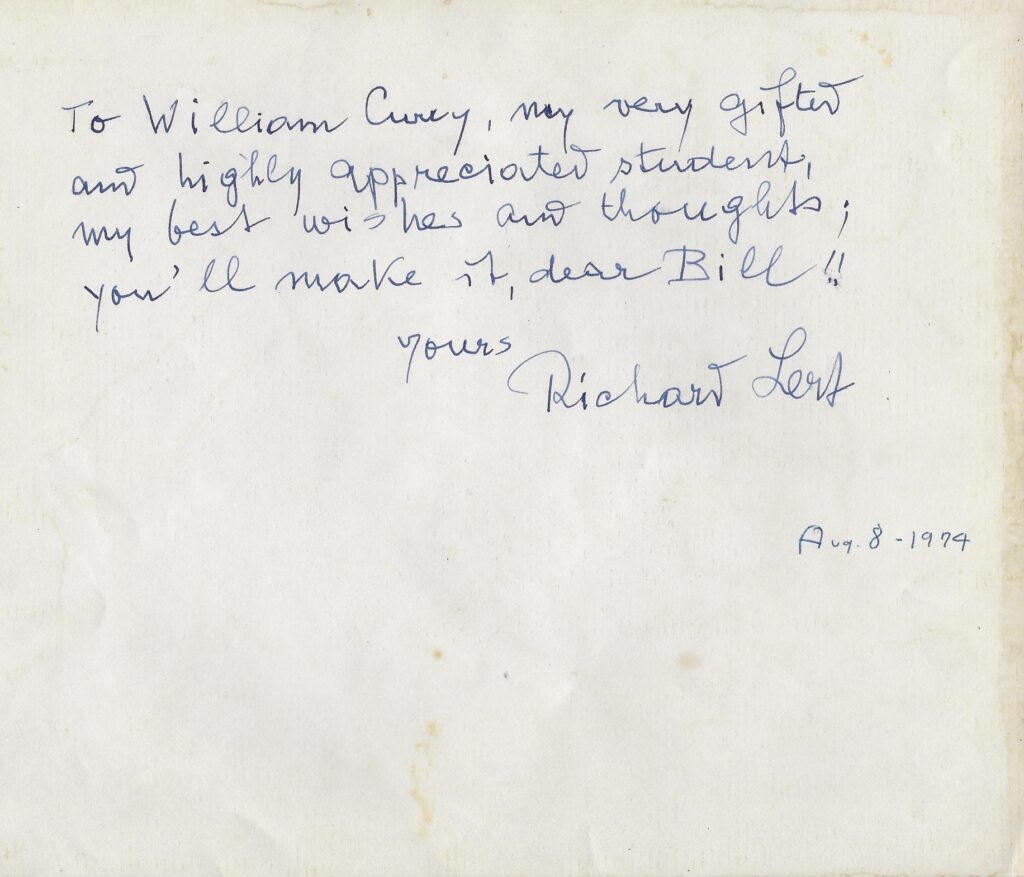

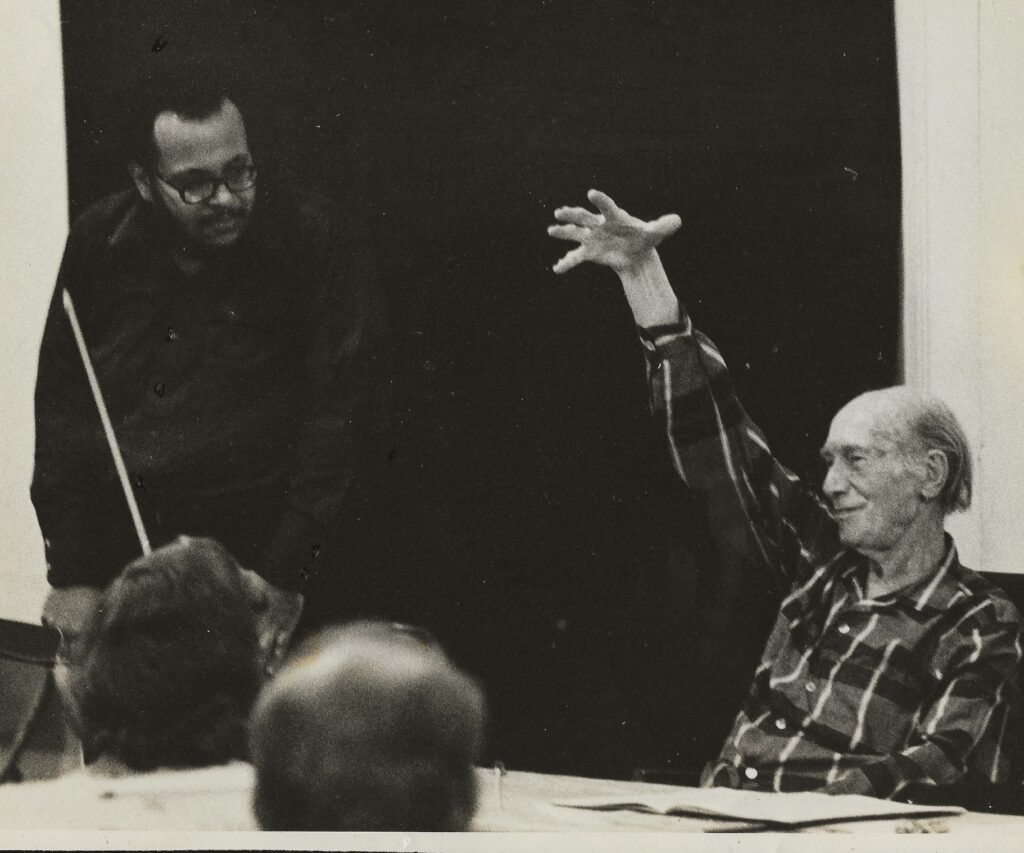

The person who did that for me was Richard Lert, whom I first met in 1974 at the American Symphony Orchestra League Conductors’ Workshop in Orkney Springs, Virginia. I was 18—the youngest of that year’s group of twenty students by a full ten years. And at age 89, Lert stood out to me as both head teacher and a true legend in conducting circles. In the mid 1920’s, he had been one of the conductors of the Berlin State Opera, and he had worked with Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, and other luminaries in the years before. Little did I imagine that he would soon become my mentor, or how that would come about.

The first piece I conducted that summer was the Finale of Tchaikovsky’s 5th Symphony. I had never conducted such a wonderful orchestra, and I was elated that they absolutely exploded under my direction. It was a prophetic moment for me and confirmed the astute observation by the great post-Romantic composer Max Reger that great interpretations come from artists who have a strong affinity for the work. Every musician and audience member who has heard me conduct Tchaikovsky senses that he is one of my soulmate composers. In such moments, interpretive decisions come about intuitively, from feeling the message of music. One moves through the work with the somnambulistic certainty of a sleepwalker. The day after my success with the Tchaikovsky, Lert took me aside and gave me an autographed picture of us at this event. One the back, he had written, “You’ll make it, dear Bill!!” For the rest of that summer, I was “teacher’s pet,” and I hung on his every word.

I soon learned that the 5th Symphony was a Richard Lert “specialty.” He had learned the piece as an assistant to Artur Nikisch, the greatest symphonic conductor of the first two decades of the 20th century. It was Nikisch’s volcanic interpretation of Tchaikovsky’s 5th that had rescued it from oblivion following its disastrous premiere (poorly conducted by Tchaikovsky). It’s been decades since that summer, yet every time I have conducted this piece, I have benefitted from the advice he shared with me—thoughts from two of its greatest interpreters.

Among Lert’s accounts of his musical past, the most stunning was that he had actually seen Brahms conduct! In 1896, when he was 11, Lert was taken to see Brahms conduct a rehearsal with a female chorus. He was surprised most by two things, which did not belong to the typical image of Brahms as burly, bearded curmudgeon: he had a very high-pitched voice, and he cried when he conducted his own compositions.

It was easier for me to believe the latter than the former. Brahms with a very high voice? This veritable beer barrel of a man? I doubted Lert’s recollection until 30 years later when I read Jan Swafford’s excellent biography, Johannes Brahms. If there is a better book about Brahms as both man and musician, I do not know it. Swafford—a composer himself—painstakingly analyzes the myths and the realties, and in the process, he finds the real Brahms, as opposed to the image that the composer invented for himself.

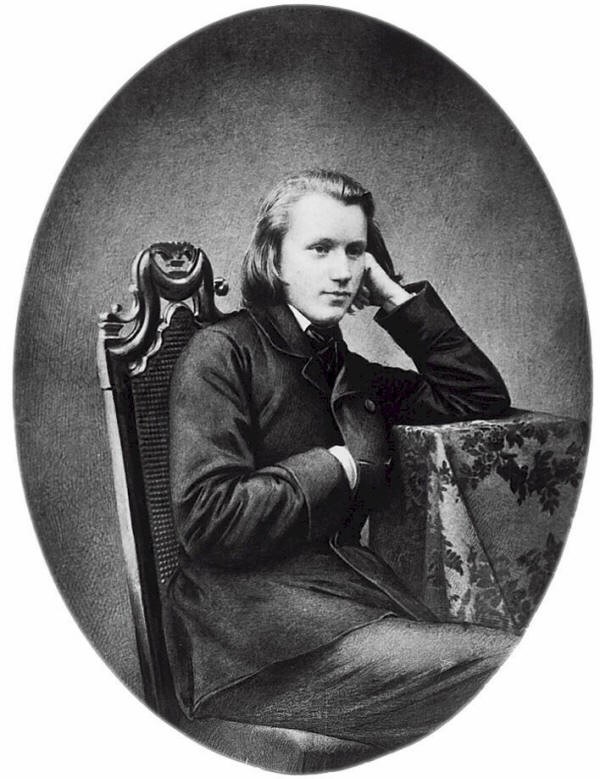

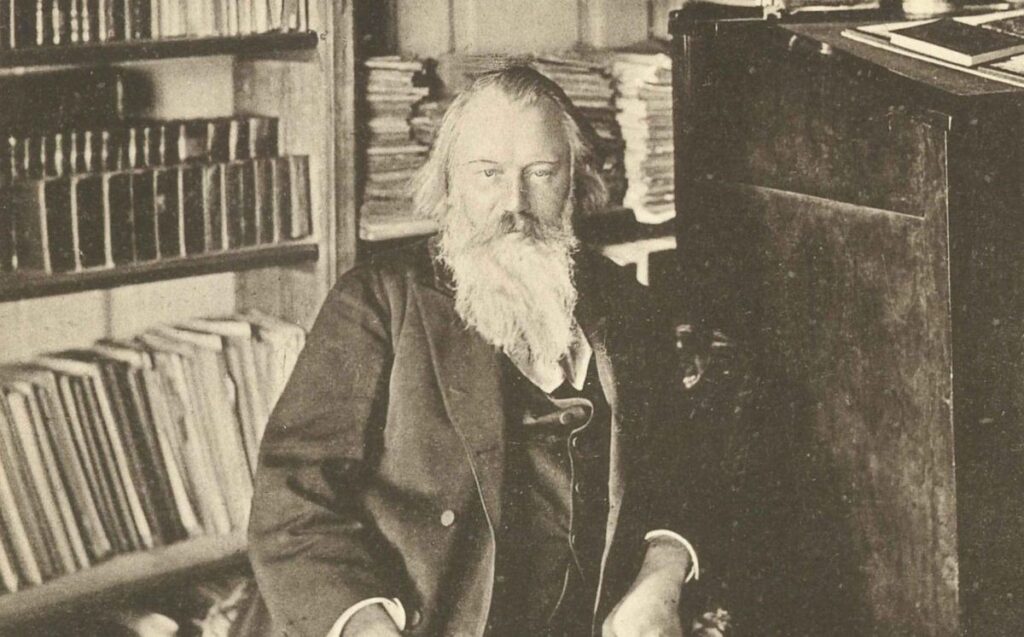

Johannes Brahms at 20.

For instance, it is not generally known that when Brahms was in his teens, he looked to most (with his long blonde hair and cherubic features) like a pretty girl. Added to that was the fact that his voice did not begin changing until he was in his mid-20’s and he was unable to grow facial hair until his late 20’s. He grew up in a poor, rough neighborhood, and one shudders to think of the teasing this young man-all of five-foot-three- must have received from his peers.

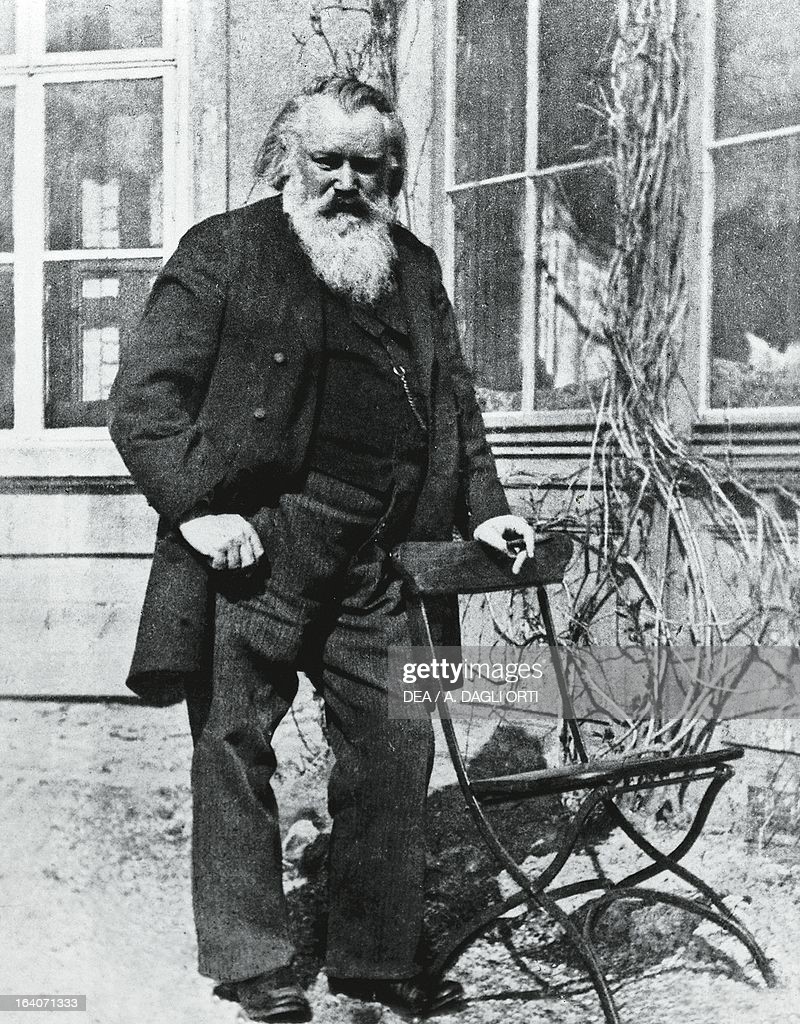

Johannes Brahms at 25.

At age 30.

Over the decades of studying Brahms’ orchestral music, I’ve been made aware of certain unconventional and abstruse qualities he exhibits, both as a composer and as a person describing his own work. One such mystery involves his tempo markings. With few exceptions, every piece of Western music from 1700 on has been given a tempo marking by the composer at the beginning of the piece—e.g. slow, fast, moderately fast, etc. But Brahms 1st Symphony begins instead with the indication “Un poco sostenuto” (“a little sustained.”) That refers only to length of notes and is no help at all regarding tempo! Brahms knew very well that his omission here would lead to endless speculation about a correct tempo. And indeed, this opening has been performed as everything from a funeral dirge to a moderately fast-paced allegro.

Brahms is even more puzzling in some of his comments about his own work. His 2nd Symphony, written during a summer outing in the country, is regarded by many as one of the most open-hearted, sunny, and accessible of his symphonies. Yet, before the work’s premiere he described it to his publisher as being “so melancholy that you will not be able to bear it.” The 3rd Symphony contains a melodic motto that translates as “Free but happy.” But a close study of the score reveals that Brahms, the life-long bachelor was more Free but lonely. For me, Brahms is always ‘hiding something,” both personally and professionally.

And the mystery has resonated for me even more fully in the Finale of his Symphony No. 4 in E minor, the last of his symphonies. Ironically, this was the first Brahms symphony I conducted. A mature work, it is usually a closed book until you are 50 (or so one conductor told me). Yet there I was at 23, all energy and enthusiasm for the project. I made a good enough impression, but I vividly remember thinking at the concert, in the middle of the Finale, “I have no ending!” At that moment, I felt strongly that the piece doesn’t offer a satisfactory ending for the 40-minute symphonic edifice that comes before. I knew that Brahms himself could not be at fault (or could he be?) I did several more performances of the work trying to solve this musical Gordian knot, but I gave up in 1980. For the next 39 years, Brahms’ 4th Symphony was the one work in the entire standard repertoire that I avoided programming, because of its “non-ending.”

Then, two years ago, I returned to study the Finale with a fresh, objective mind. The Finale is always described as evoking stark, wintry sounds and angry emotions. Much of the music rages in this Finale, like Shakespeare’s King Lear on the stormy heath in Act 3, Scene 2, defying the elements and standing alone apart from all humanity: “Blow winds, and crack your cheeks! rage! blow!” But on more careful study, I realized that the hidden “heart” of this movement—the key to understanding ALL the rest–is the slow and quiet central section of the piece.

It begins with a melancholy, yearning passage in the solo flute. A striking thing about it is that the notes lie in the lower third of the flute’s register. That timbre deepens the sadness of this incredibly intimate moment. (And DSO Principal Flutist, Erin Munnelly, plays this as beautifully as I’ve ever heard it.) Then the key switches to the major, one of the very few times that this happens in this movement.

At this point, the music (scored for woodwinds and brass) takes on the character of a hymn. The dynamic is marked “very soft”—a rare dynamic in Brahms. The effect is of a soft, internal prayer. It seems that Brahms is preparing for the “happy ending” that every symphony beginning in a minor key had featured since Beethoven’s 5th. Has spring finally arrived?

But then, something goes quietly but disturbingly wrong during the wind chorale. The radiant and secure warmth slowly dissolves into despair. It is then that the flute unexpectedly returns, and this time, the mood is even bleaker than at the start of the solo. Brahms indicates in the music that the flute should slow down little by little, its energy fading as the final phrase slides into silence. And then, as the strings land softly on an inconclusive chord, Brahms indicates that this note should last as long as the conductor chooses.

In my opinion, the last ten seconds of this section are never played properly. The flute almost never heeds the composer’s indication to slow down. And conductors, anxious to get on with the loud interruption coming up, impatiently shorten the real drama at the core of the piece: that terrible moment of looking into nothingness where time stands still.

There will be no happy ending in this symphony because, in this piece (and for Brahms), it would be too easy—a fake, a lie. The wintry chords abruptly return in the winds, but this time they are louder, angrier, and more invulnerable. The tempo gets faster, the mood becomes more frenetic, and we are hurled into an abyss of nihilism. As Swafford puts it: “[Brahms] allows the darkness to stand, gives tragedy the last word” (157).

This unusual ending was much commented on at its premiere and subsequent performances. Again, from Swafford:

After Brahms died, conductor Felix Weingartner wrote of the finale: “I cannot get away from the impression of an inexorable fate implacably driving some great creation, whether it be an individual or a whole race, toward its downfall. . . . This movement is seared by a shattering tragedy, the close being a veritable counterpart to the paroxysm of joy at the end of Beethoven’s last symphony.” (157)

And with this movement, the 57-year-old Brahms boldly ends his symphonic career. The journey ends not with hope, but with defiance in the face of the unknown that all must face. Is it any wonder that I could not comprehend this piece at age 23?!

Now, at age 66, I find that happily (or unhappily) it is a “soulmate” piece at last. After 40 years of life experiences, with this DSO performance of the Finale, I finally felt I understood the structure and the emotions contained in this epic masterpiece.

We hope you will enjoy the DSO’s performance of the Finale from our November 3, 2019 concert at the Carolina Theatre!

IV. Allegro energico e passionato (Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op 98)

Johannes Brahms

William Henry Curry, Conductor

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Centennial of American Women’s Suffrage |Nov 03, 2019

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Copy Editor: Marianne Ward & Tina Biello

Digital Layout and Publication: Tina Biello & Marianne Ward

Video Mixing & Mastering: Mark Manring https://www.manring.net/

Celebrating Maestro Curry’s 50 years conducting & 11 years with the Durham Symphony!

“Monday Musicale with the Maestro”

would not be possible without your support!

Thank you for being a important part of the

Durham Symphony Orchestra family!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and a grant from the Triangle Community Foundation.

.