Monday Musicale with the Maestro – March 22, 2021 – Billy Strayhorn and Duke Ellington

When I was guest conducting the New York City Opera in 1994, my most unforgettable “off night” was spent listening to a radio station featuring suites written by Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn for Ellington’s band. The occasion was the 20th anniversary of Ellington’s death, and here was four hours’ worth of some of the greatest music ever written by American composers. But at the time, these works were virtually unknown—as they are to most concertgoers today! So, over the years, I have especially enjoyed conducting selections from these suites, as arranged for symphony orchestra. Our DSO performance today features one of these pieces by Ellington and Strayhorn: “The Happy-Go-Lucky Local,” from Deep South Suite.

Edward Kennedy Ellington (1899-1974) was the greatest composer of big band jazz. His nickname, Duke, came from his elegant manner—no doubt inspired by his father, who was a butler at the White House. Between 1929 and 1974, Duke and his jazz band were international celebrities, and I heard them perform while I was attending the Oberlin Conservatory. The piece I remember most vividly was the quiet and extremely beautiful encore “Lotus Blossom,” played by Duke himself at the piano. I was intrigued to learn that it was not his own composition, but one by Billy Strayhorn (1915-1967).

When I heard this Ellington performance, it was seven years after Strayhorn’s death, and Ellington himself would be gone only a few months later. I thought “Lotus Blossom” was the greatest composition of the night, and clearly the piece was of special significance to Ellington (who actually calls it his “favorite” in the video above). In my teens I played the baritone saxophone in several jazz bands and combos, so I went backstage to meet one of my heroes, the band’s baritone saxophonist, Harry Carney. He told me that ever since Strayhorn’s death, Duke had ended every concert with that piece, in memory of Strayhorn.

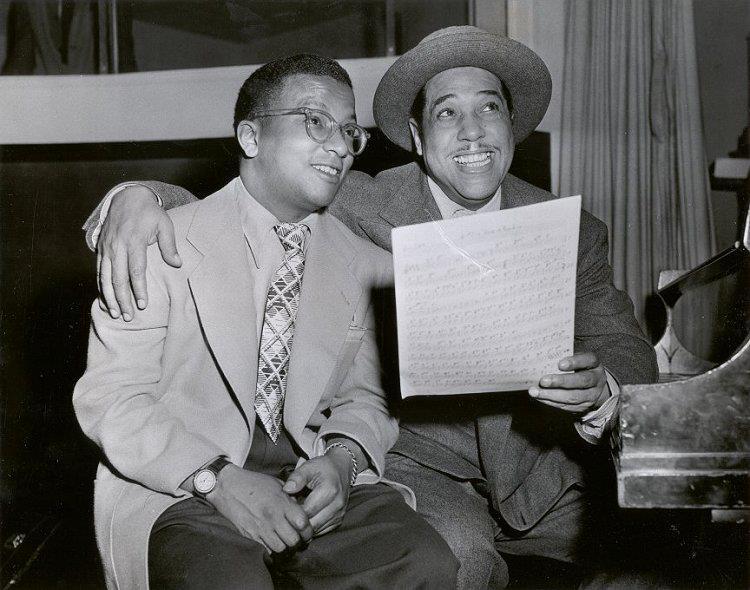

Billy Strayhorn with Duke Ellington

Billy Strayhorn was born in Dayton, Ohio, but soon moved to my hometown, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Since his mother’s family lived in Hillsborough, North Carolina, Billy was often sent there for the summer. And it was there, with his grandmother as the primary influence, that Billy first fell in love with classical music. While in Pittsburgh, he studied music with Carl McVicker, whom I met as a teen. It was Billy’s dream to be a classical pianist, but race was a barrier to that goal, as we saw also with Nina Simone and Scott Joplin in our earlier Monday Musicales.

But Strayhorn also fell in love with jazz and often played piano in clubs and private homes, such as the one where my parents heard him play in the early 1930s. In 1933 Strayhorn heard a Pittsburgh performance by Ellington and his band that caused him to take this music even more seriously. And by 1938, at age 23, he had plucked up the courage to introduce himself to Ellington after another performance in Pittsburgh. In his book Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn, David Hadju describes this fortuitous meeting. Duke asked Strayhorn to play some of his compositions, and on hearing these, Ellington was mesmerized, recognizing instantly that he was hearing the work of a young musical genius. Duke then called excitedly for Harry Carney, his closest and most trusted friend in the band, to hear his discovery. Carney was equally impressed. Duke gave Strayhorn some musical assignments to test him and told him to come back. When Strayhorn more than passed this test the next day, their 25-year collaboration had begun. Strayhorn soon became, pianist, composer, and arranger for Ellington’s band, and Ellington invited Strayhorn to live with him until he found a place of his own in New York. When Billy first arrived in New York City, he had directions from Duke concerning how to get to his home, and one of these was to “take the A train.” This is how Strayhorn came to write Ellington’s theme song of the same name (Hadju 80-82).

The two were inseparable, both as friends and musicians, and often composed pieces together, each picking up where the other had left off. Even today, music historians do not agree concerning who wrote what in which piece! After Strayhorn’s death, Ellington said of this musical marriage, “Billy Strayhorn was my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brain waves in his head and his in mine” (Duke Ellington, Music is My Mistress 156).

In their work together, Strayhorn stayed out of the limelight, a situation which seemed to suit his shy and warm persona and had another advantage besides. The jazz world was aware that Strayhorn was gay, and he took no pains to hide it in his own community. Yet it was a difficult era for a Black, gay artist. At best, you might be shunned—at worst, killed. So the role of gay Pop music artist was not “practical,” to say the least. Ellington said often of their working arrangement, “Strayhorn does a lot of the work, and I take all the bows” (“Billy Strayhorn,” Wikipedia,19 January 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billy_Strayhorn).

In Lush Life, David Hadju notes that Ellington was totally accepting of Strayhorn’s homosexuality, a fact vital to his life and career. He quotes Duke’s son Mercer as saying, “Pop never cared one bit that Strayhorn was gay. He backed up Strayhorn all the way” (79). Hajdu observes,

Another gay black musician who was a close friend of Strayhorn’s evoked the virtue of Ellington’s patronage emphatically. “For those of us who were black and homosexual in that time, acceptance was of paramount importance, absolutely paramount importance. Duke Ellington offered Billy Strayhorn that acceptance. That was something that cannot be undervalued or underappreciated. To Billy, that was gold” (79).

Duke Ellington with Billy Strayhorn

Strayhorn is now much accepted and beloved by all those who love jazz. And the town of Hillsborough has shown their pride in their “hometown” son in many ways, including a festival in his honor in February 2019, a mural, and a plaque commemorating his boyhood home there.

For Ellington, Strayhorn’s legacy was not only musical, but a matter of character as well. In his book Duke Ellington’s America, Harvey G. Cohen notes Duke Ellington’s advocacy for what he called Strayhorn’s “four major moral freedoms” (485). Ellington worked these into a moving passage of spoken text in his Second Sacred Concert (1968), the most expansive of three concerts in which Ellington testified to his own faith and beliefs. “It’s Freedom,” captures Strayhorn’s own ethos as Ellington saw it:

“Freedom from hate, unconditionally; freedom from self-pity (even through all the pain and bad news); freedom from fear of possibly doing something that might possibly help another more than it might himself; and freedom from the kind of pride that might make a man think that he was better than his brother or his neighbor.” (Cohen 485)

We hope you will enjoy the DSO’s performance of “The Happy-Go-Lucky Local” from the Ellington/Strayhorn Deep South Suite. This is one of the many “train pieces” that Duke and Billy were responsible for, though “Take the A Train” and “Daybreak Express” may be more widely known.

Here it is, in a very tasteful orchestral arrangement by Chuck Israels, as performed at the Hayti Heritage Center on May 29, 2016.

The-Happy-Go-Lucky Local (The Deep South Suite)

Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, arr. Israels

William Henry Curry, Conductor

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Tribute to Duke Ellington|Hayti Heritage Center|May 29, 2016

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Copy Editor: Marianne Ward & Tina Biello

Digital Layout and Publication: Tina Biello & Marianne Ward

Video Mixing & Mastering: Mark Manring https://www.manring.net/

Celebrating Maestro Curry’s 50 years conducting & 11 years with the Durham Symphony!

“Monday Musicale with the Maestro”

would not be possible without your support!

Thank you for being a important part of the

Durham Symphony Orchestra family!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and a grant from the Triangle Community Foundation.

.