Monday Musicale with the Maestro – April 5, 2021 – Jazz Master David Baker and “Serious Fun”

The rejection of edgy new musical styles by more “conservative” elders has been an issue, probably, since the dawn of the Age of Man. Darn those crazy kids with the bumpin’-and-thumpin’ noises they make on those melons and tree logs. And what about those nasty words they howl while they’re doing that? Those aren’t the pretty songs WE used to sing!

In part, of course, the young are merely freeing themselves from tradition and parental control as they begin exploring their separate identities. The principal theme of Wagner’s opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (“The Mastersingers of Nuremberg”) is the tension between the older statesmen of music and the new songs that young firebrand Walther von Stolzing composes. The main character (Hans Sachs) is the wise musician who, though bewildered by Walther’s innovations, is mature enough to recall the time when he was young and his elders thought his songs were “way out there.”

I was in my mid-30s when the furor arose over rap songs (and particularly the lyrics). The anger reached such a crescendo that the U.S. Congress, with the guidance of Tipper Gore (wife of Vice President Al Gore) demanded that warning labels be applied to recordings with lyrics deemed offensive. Twenty years prior, a crowd of elders over 30 had greeted with almost universal disdain the “jarring” music of rock-and-roll—and this included what we now regard as classic Beatles tunes! When American men saw their teenaged sons imitating the Beatles’ long hair, many men were enraged that their sons were “trying to look like girls.” Earlier still, Elvis had shocked some “mature” audiences by comparing a woman to a hound dog (“crying all the time”) and by his unique gyrations. Well, I don’t let my daughter Nikki watch him when he appears on TV. It might give her. . .ideas.

By the way, my mother ADORED Elvis. Whenever he appeared on TV, my little brother and I were banished from the room so she could more completely focus on. . .what he was doing.

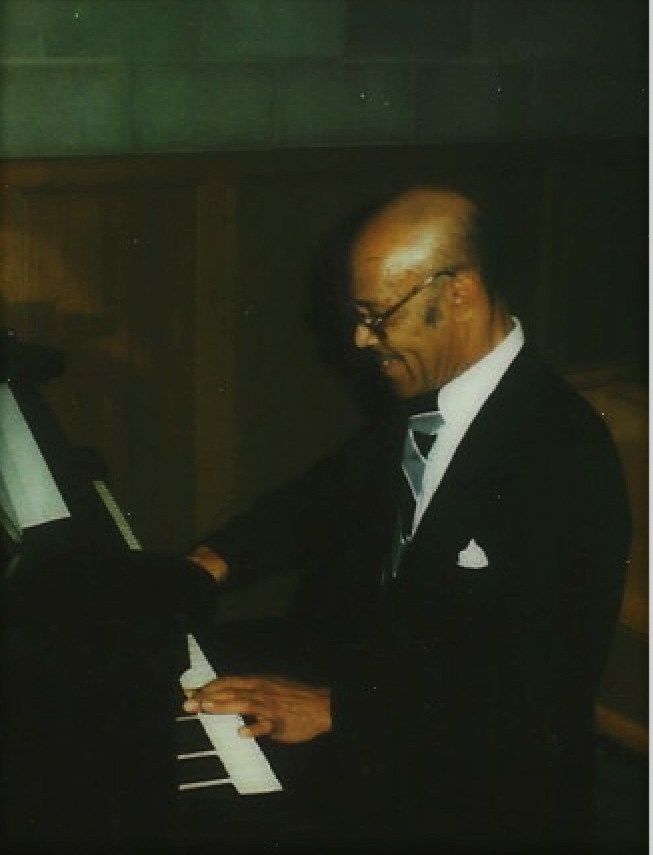

As we know, the results of such innovations are sometimes spectacular—but the process of acceptance is messy and filled with tension. Many have now forgotten the colossal stigma that jazz first had in this country, even among African Americans. As a case in point, I offer my father’s own love of jazz and his early experience (or attempted experience) in studying the saxophone.

My father (William Henry Curry, Sr.) at church, circa 1980.

My father (William Henry Curry, Sr.) was raised by his maternal grandparents. I know next to nothing for sure about the circumstances surrounding this. It could be that his mother died immediately after giving birth to him and that his father abandoned the baby in the aftermath. I know only that my father’s memories of his grandparents seemed to be centered on how strict and stern they were. The only story I recall his telling about them was a traumatic one involving his passion for music.

As a teenager in the mid-1920’s, my father loved jazz (the pop music of his time), and he very much wanted to play the saxophone. He laboriously saved his money so he could buy one though the mail. When the great day arrived, he took his new prized possession in hand along with its instruction book. Now he was going to learn to play jazz! But he hadn’t been playing for long before his grandfather barged into his room, tore the instrument out of his hands, and threw it out the third-story window, destroying the saxophone in the process. Then his grandfather began a long tirade, saying that “Jazz is the Devil’s music” and that he should be ashamed of himself for wanting to be involved in that.

I first heard this story from my father when I brought my baritone saxophone home for the first time and was practicing it in my upstairs bedroom. It was only then that he came into my room, shared the story of his own desire to play the saxophone, and described the hurtful experience that came with it. Half a century has passed since that moment, but I can still see my father’s bemused face, smiling despite the tears on his cheeks. For years, when I thought of this incident, I believed that his grandfather’s take on jazz wasn’t the average response at the time. But 25 years ago, when I began research on the early age of Jazz, I learned the truth.

As I have mentioned before in these blogs, jazz has its roots in ragtime, a syncopated music with rhythms wholly unrelated to those of European classical music or early American folk music. The principal exponents of ragtime were African American pianists such as Scott Joplin. And because this music originated from Blacks, white Americans were deeply suspicious of it at first. To read the racist criticism of ragtime by contemporary writers is indeed chilling.

Below is a sampling from Charles Hamm’s Music in the New World (1983), pp. 398-399:

“Ragtime is symbolic of the primitive morality and perceptible moral limitations of the negro race. America is falling prey to the collective soul of the negro.”

–“Musical Impurity.” Etude magazine (January 1900): 16.

“It is an evil music that has crept into the homes and hearts of our American people regardless of race and must be wiped out as other bad and dangerous epidemics have been exterminated.”

–Paul C. Carr. “Abuses of Music.” Musician magazine

(October 6, 1900): 229.

“In Christian homes, where purity of morals is stressed, ragtime should find no resting place.”

–Leo Oehmler. “Ragtime, A Pernicious Evil and Enemy of True Art.”

Musical Observer (September 1914): 15.

Clearly my great-grandfather was not alone in thinking that a corrupting force drove this music. And through the end of the 1920s, until jazz was finally embraced by mainstream white listeners, it still bore a racial stigma.

Even those who championed its expressive content were sometimes quick to add that it lacked craftsmanship, intellectual heft, and cultural value. One of the most infamous statements of this kind came from Gilbert Seldes’ article “Toujours Jazz,” published in The Dial in August of 1923. There Seldes was quick to assert that

with all my feeling for what [the negro]instinctively offers and for his desirable indifference to our set of conventions about emotional decency, I am still on the side of civilization. To anyone who inherits several thousand centuries of civilization, none of the things the negro offers can matter unless they are apprehended by the mind as well as by the body and the spirit. So far in their jazz, the negroes have given their response to the world with exceptional naivete, a directness of expression which has interested our minds as well as touched our emotions; they have shown comparatively little evidence of the functioning of their intelligence. (vol 57, 159-60)

This was the America my parents grew up in.

After I left high school, I didn’t play the saxophone or string bass in jazz ensembles again, but I greatly enjoyed listening to jazz, my favorite pop music. In my blogs and at my concerts, I have often mentioned my all-time jazz hero, Louis Armstrong. And I hold a very special place in my heart for the artistry of two jazz piano greats, starting in my earliest years with Errol Garner.

Garner was the composer of the now classic song “Misty” and was a friend of my parents when they were growing up as teens in Pittsburgh. Here he is performing “Honeysuckle Rose” by Thomas “Fats” Waller

Erroll Garner in London “Honeysuckle Rose”

The other jazz pianist I have greatly admired is Oscar Peterson.

He combined the virtuoso technique of pianist Art Tatum (praised by the likes of Horowitz and Rachmaninoff) with the melodic expressivity of Errol Garner. For decades now I have often said, “When I grow up, I want to be Oscar Peterson!” Here he is performing “Tonight” by Leonard Bernstein.

Tonight – Oscar Peterson Trio

In the 1980s, while I was Associate Conductor of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, I became friends with jazz legend David Baker, head of the Jazz Studies Department at Indiana University, Bloomington. In 1968, Indiana University was one of the first to offer a degree in jazz, driven by Baker’s fervent belief that it must be celebrated and taken seriously as an art form.

David Baker (1931-2016) in his office.

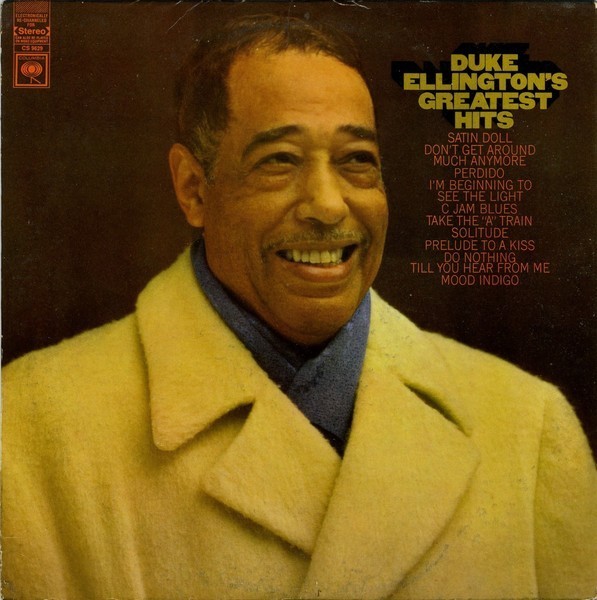

It was he who led me to understand the miraculous musical genius of Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn. He was deeply interested in the sophistication and harmonic audacity of their music. He often analyzed this duo’s jazz suites for me, pointing out how incredibly complex they were. This sophistication had not been properly honored, he believed, nor had they been given their due for eloquence and life-affirming joy. Without David’s positive influence, I might not have comprehended the full depth of these works. Their greatness is absolutely comparable to other giants of the 20th century—including Ravel and Gershwin, both of whom adored jazz and incorporated it in their works.

One of Ellington’s most moving compositions is aptly titled “Solitude.” He made many recordings of it, but my favorite by far was made in 1957 and evokes another personal memory of jazz related to my father.

In the early 1980s, I went home to visit him. It was then several years after my mother (his wife of 33 years) had passed away. My father had let me know repeatedly, before and after her death, how much he had loved her and what a good woman she was. During that week with my father, I noticed that he was in good spirits. My dad had the greatest smile I have ever seen, and no one reacted to a joke with as much eruptive glee as he did. Then one day, while I was in my bedroom listening to this recording of “Solitude,” my father came in.

It was he who had first introduced me to Ellington’s music, and while I don’t recall what he told me back then, I remember the look on his face when speaking of it. That alone had been enough to tell me that, to him, Ellington was sacred—the very best of all the jazz giants. Except when he talked about my mother, I had never seen such a serious or awestruck look on his face.

So that day in the 1980s, the scene was perfectly set for his news. While “Solitude” continued in the background, he came into the room and very shyly told me that something wonderful had happened that year. He was in love again! He asked if I could give him my permission to marry this woman. Of course, I was stunned by the question and quickly and happily gave him my consent. And then he smiled and left the room. . .and I was left alone with the concluding minute of Duke’s reflective coda to “Solitude.” It goes without saying that whenever I hear this recording, memories of my parents and my youth come flooding back in a torrent of nostalgic emotion.

Duke Ellington’s Orchestra – Solitude

A few weeks ago, we featured the DSO performance of “The Happy-Go-Lucky Local,” from the Ellington/Strayhorn Deep South Suite. Here is another wonderful movement from that work, “Magnolias Dripping with Molasses,” played live in 1946 by Ellington and his band.

The Deep South Suite: Magnolias Just Dripping with Molasses

(Live November 10th, 1946)

Provided to YouTube by The Orchard Enterprises

Twenty or so years after the passing of Ellington and Strayhorn, David Baker began a long association with the Smithsonian Institute. For many years, he was the conductor of the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, and he was a recipient of the “American Jazz Masters” award. It was during his time there that the Smithsonian commissioned Baker to catalogue the complete compositions of Duke Ellington, a truly Herculean task.

The last time I saw Dave, we had happened to run into each other in an airport lounge as he was travelling back from the Smithsonian. I recall commenting that he looked especially exhausted. He smiled wearily, explaining that though he’d already catalogued 1000 pieces for the Smithsonian, there were at least that many remaining to be found and archived. Nevertheless, he said, it was a great honor to be charged with this responsibility.

I remember thinking, then as now, that nobody could have been more appreciative of this treasure trove of uniquely American music. He explained at the time that, as far as he knew, no writer had ever written about the considerable sense of musical humor contained in this music, which at the same time represented the highest standards of craftsmanship and originality. His phrase for this music was “serious fun,” and I have never forgotten that perfect labeling. This is indeed music that is elegant, substantial, perfectly composed, witty—and yes, wildly entertaining fun!

David Baker was also a cellist and a first-rate composer. Throughout his long career, he was commissioned to write works for such luminaries as cellist Janos Starker, violinist Ruggerio Ricci, and saxophonist Dexter Gordon. Over the decades, I have conducted many of David Baker’s compositions, including the world premieres of some of his orchestral works. And several times, he joined me as a jazz cellist in his arrangement of Ellington/Strayhorn’s last big hit, “Satin Doll.”

For the DSO’s April 2, 2016 concert at the Carolina Theatre (NC Music and All That Jazz), I programmed David’s arrangement of “Satin Doll,” our DSO featured selection for today. Our soloist was the brilliant saxophonist Brian Miller. In the weeks before the concert, I was looking forward to sending our recorded performance of this work to David. But a few days before the event, we lost him at the age of 84. This year would have been his 90th birthday, so I would like to dedicate this blog and this selection to his memory.

Satin Doll

Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn, arr. David Baker

Durham Symphony Orchestra

William Henry Curry, Conductor

Brian Miller, saxophone | Paul Creel, bass

Kevin Van Sant, guitar | Thomas Taylor, drums

Andrew Berinson, keyboard

NC Music and All That Jazz | Carolina Theatre | April 2, 2016

I like to call teaching and nursing the two “God professions.” To me, those people are Earth angels,” and I have been blessed to be both giver and receiver in these powerful and healing interactions. The fact that jazz is now considered to be sophisticated classical music instead of a puerile, degraded genre, is partially due to the devotion of educators like David Baker to this great and uniquely American art form. David often said to me that his proudest achievement was to be a wonderful teacher and mentor for his students. I was lucky to be one of those who knew him and learned from him.

As Quincy Jones puts it in his “Foreword” to Monika Herzig’s David Baker: A Legacy in Music,

He always chose his teaching and his students as his principal calling. In a society that most commonly rewards glamorous careers with a focus on highly visible personalities, the choice to dedicate one’s life to helping others achieve their aspirations is a mark of a truly selfless and kind person.

Quincy Jones with David Baker

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Copy Editor: Marianne Ward & Tina Biello

Digital Layout and Publication: Tina Biello & Marianne Ward

Video Mixing & Mastering: Mark Manring https://www.manring.net/

Celebrating Maestro Curry’s 50 years conducting & 11 years with the Durham Symphony!

“Monday Musicale with the Maestro”

would not be possible without your support!

Thank you for being a important part of the

Durham Symphony Orchestra family!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and a grant from the Triangle Community Foundation.

.