Monday Musicale with the Maestro – June 20, 2022 – Dark Testament – Honoring Juneteenth and Durham’s Pauli Murray

Dear Friends of the Durham Symphony Orchestra,

Monday Musicale with the Maestro. Dark Testament – Honoring Juneteenth and Durham’s Pauli Murray.

As always, you can read the full text or catch up on all of the archived posts in the Conductor’s Corner!

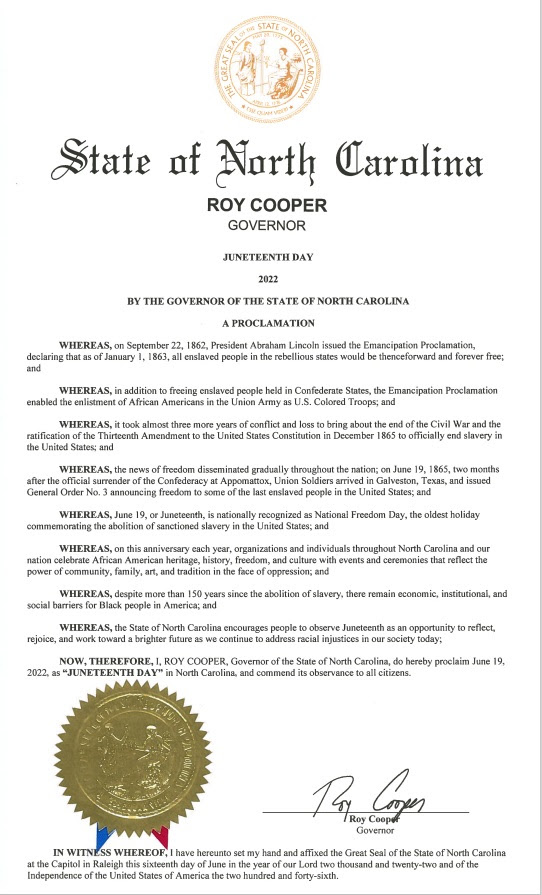

I was delighted to awaken on the morning of Juneteenth 2022 to find Governor Roy Cooper’s beautifully worded proclamation:

The creation of my latest piece, Dark Testament, was inspired in part by the establishment of Juneteenth as a federal holiday in 2021. The work was the result of a commission from Professor Tonu Kalam and the UNC Symphony Orchestra, with matching funding provided by Arts Everywhere. That conductor and ensemble premiered it on April 28, 2021. In 2022, I revised it to clarify its colors and message. On April 10, 2022, at the Hayti Heritage Center, I conducted the premiere of this version with the Durham Symphony Orchestra during our tribute to the legacy of Pauli Murray, presented in partnership with the Pauli Murray Center. The piece takes its title from a book of poems by Pauli Murray.

The work is scored for string orchestra and solo string quartet and was inspired by African American spirituals. The importance of these spirituals cannot be overestimated. They are a melting pot of African music and Euro-American hymns and were the incubator for many musical genres, including, blues, jazz, gospel, R&B, rock ‘n’ roll, and hip-hop. In fact, one could say there is no authentic American-sounding music that has not in some way been influenced by spirituals.

These songs were born into the misery of slavery. For me, the most moving and meaningful description of the true message of these songs comes from Frederick Douglass. He was born a slave, escaped to freedom, and became an abolitionist. In his memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, he writes that enslaved people

would make the dense old woods, for miles around, reverberate with their wild songs, revealing at once the highest joy and the deepest sadness. . . They would sometimes sing the most pathetic sentiment in the most rapturous tone and the most rapturous sentiment in the most pathetic tone. Every tone was a testimony against slavery and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains. The hearing of these wild notes always depressed my spirit and filled me with ineffable sadness. I have frequently found myself in tears while hearing them. (47-48)

Dark Testament is in three connected sections. The sub-theme of Dark Testament is a tribute to three heroic African American women who, despite all odds, persevered and achieved memorable contributions for their country. The opening movement pays homage to Mahalia Jackson, who, at the height of her career, was called “The Queen of Gospel.” She was well-known for her version of “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round.”

Movement 1: “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round”

famous March on Washington, DC

The piece begins with a quodlibet of spirituals found in a book titled Slave Songs of 1865. Each member of the solo string quartet plays a different spiritual in a different tempo. This is suddenly interrupted by the defiant song “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round.” The lyrics portray the attitude of someone who, despite the direst of circumstances, will not allow themselves to be defeated. The rhythms here are redolent of those found in gospel songs. In this section and throughout the remainder of the piece, the string quartet offers solos and is joined by a string bass. Next, we hear the ebullient spiritual “Wait, Mr. Mackright.” This buoyant melody transforms the militant mood into something less assertive and more joyous. The first song returns, and the music slowly fades away.

Movement 2: “Love and Loss”

The famous spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” frames this movement, which is an elegiac tribute to Pauli Murray. Born in Baltimore in 1910, Murray was raised in Durham by her maternal aunt and namesake, Aunt Pauline (a teacher). She barely knew her accomplished and charismatic parents, Agnes & Will, whose story took a tragic turn very early in her life. But as she explains in her autobiography, Song in a Weary Throat: Memoir of an American Pilgrimage, their history and “courage in adversity” had a profound influence on her life and “helped [her] at an early age to face the baffling reality of human bereavement” (17). Her mother, a nurse, died of a massive cerebral hemorrhage when Pauli was three (14). Her father—a teacher who “dabbled in poetry,” composed music, and played piano and flute (10)— suffered from depression and violent moods after battling typhoid fever and encephalitis and was committed to a mental institution three years after his wife’s death (16). Pauli met him only once during her childhood, and by her thirteenth birthday, he was gone—beaten to death by a white guard (a temporary, untrained worker) at the hospital (72).

Murray’s life as a Renaissance Woman, educator, and universal advocate for freedom and equality was filled with turmoil and triumph. She became a lawyer and legal scholar, a poet and the writer of a brilliant autobiography. She was a civil rights and women’s equality activist and the first African American female priest ordained in the Episcopal Church. Though the matter was private in her time, her gender identity was fluid, and some historians now categorize her as being transgender. In 2012, the Episcopal Church sainted Pauli Murray for her work in support of human freedom and dignity and for her efforts to reconcile divisions between races, sexes, and economic classes. Murray’s poem, “Dark Testament,” ends with this stanza:

Then let the dream linger on.

Let it be the test of nations,

Let it be the quest of all our days,

The fevered pounding of our blood,

The measure of our souls—

That none shall rest in any land

And none return to dreamless sleep,

No heart be quieted, no tongue be stilled

Until the final man may stand in any place

And thrust his shoulders to the sky,

Friend and brother to every other man.

(Murray, Dark Testament and Other Poems 19)

Movement 3: “The Underground Railroad”

This movement begins with two modern spirituals that I wrote a decade ago. The first is a hymn that is later turned into a jazz waltz. The second song, “The Underground Railroad,” is first stated by the solo violin, and then we hear a series of transformations of that melody. The two spirituals from the first movement return, ending the work with joy and optimism.

This movement is a tribute to Harriet Tubman, one of the courageous conductors (guides) of the fabled “underground railroad.” This was neither an actual railroad nor was it underground. Rather, it was a series of secret routes and safe places that thousands of slaves used to escape to freedom from the South to the North or Canada. Harriet Tubman risked her life dozens of times on these journeys. During the Civil War, she was a Union spy, and after the war she became an activist for women’s suffrage.

Though the “railroad” here is a symbolic one, I could not resist including in this movement the sounds of steam engine trains! In the Black community, trains have always been a metaphor for the journey from despair to hope, and this is the emotional and spiritual journey I have tried to describe in Dark Testament.

We hope you will enjoy the Durham Symphony’s performance of Dark Testament from April 10th, 2022, at the Hayti Heritage Center. Happy Juneteenth!

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Copy Editors: Suzanne Bolt and Tina Biello

Digital Layout and Publication: Tina Biello and Marianne Ward

Audio by Mark Manring

Thank you for being a important part of the Durham Symphony Orchestra family! We appreciate your support and vital impact on our community!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Ivy Community Service Foundation of Cary, Inc., the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and grants from the Triangle Community Foundation, The Mary Duke Biddle Foundation and the F. M. Kirby Foundation.