DSO Celebrates July 1st: Pauli Murray’s Feast Day – An American Saint

Dear Friends of the Durham Symphony Orchestra,

From the pen of Maestro William Henry Curry. The Durham Symphony Orchestra celebrates July 1st. Pauli Murray—An American Saint

As always, you can read the full text or catch up on all of the archived posts in the Conductor’s Corner!

The life of Pauli Murray is one of those inspirational American stories reminding us how we can, despite the odds, persevere with brilliance, grace, service, and empathy to bring this country closer to fully equality for all. We are fortunate to have had her among us. Our June 20th Monday Musicale (honoring Juneteenth) included part one of our tribute to Murray as well as selections from a recent DSO concert featuring my work, Dark Testament. The piece takes its name from Murray’s collection of poetry, and the central movement (“Love and Loss”) is dedicated to Murray herself. That earlier installment focused most heavily on Murray’s early life and her legacy as poet, lawyer, and activist. Today, one day past the swearing-in of Ketanji Brown Jackson (first female African American Supreme Court Justice) it bears mentioning that Pauli Murray pushed the envelope in 1971 by applying directly to Richard Nixon for that position! Ann Branigan, of the Washington Post, wrote a wonderful article about that last January, quoting Barbara Lau (Executive Director of the Pauli Murray Center, Durham).

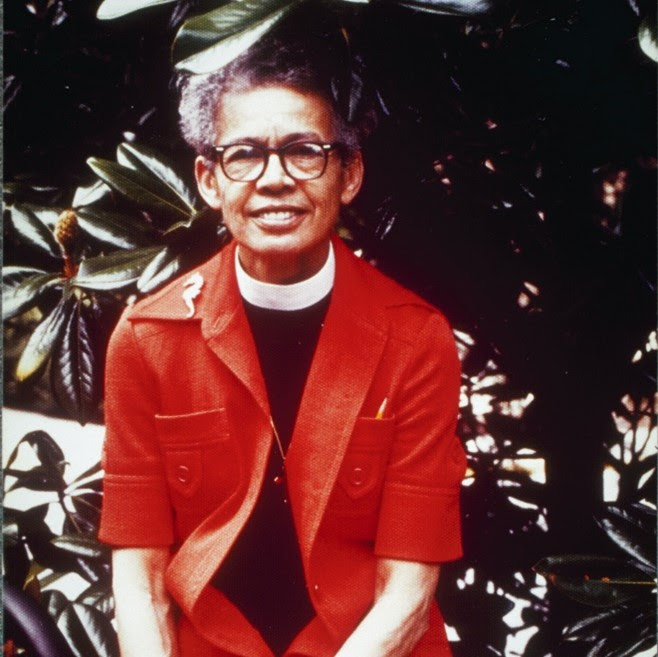

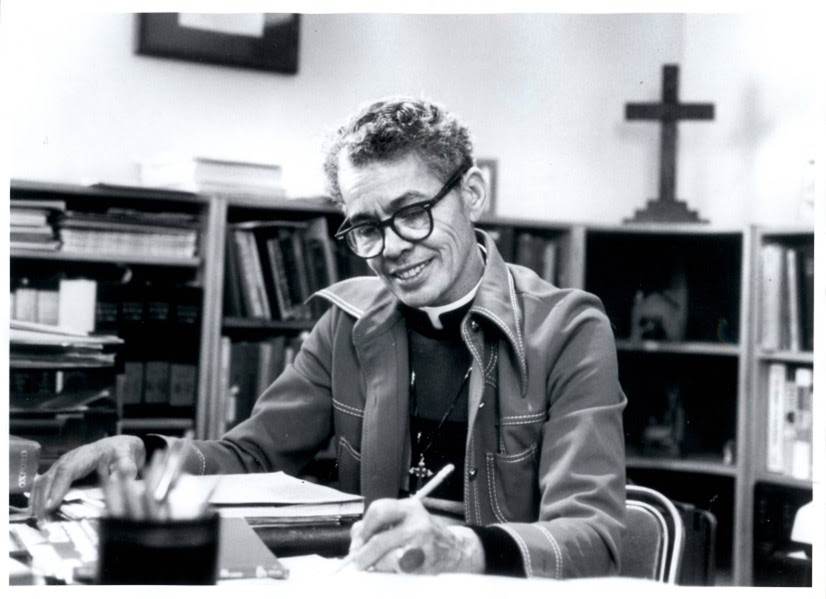

Among the most remarkable of Murray’s achievements was becoming the first Black female to be ordained as an Episcopal priest, and the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina website is a rich source of information on both her life and her work as a priest. Murray’s ordination came late in her life—after the death of her partner, Irene “Renee” Barlow, in 1973. The two had shared a deep devotion to their faith. Pauli’s grief must have been especially painful because she was not “out” (and never would be). And she had few, if any friends with whom she could share the true nature of this loss. After Irene’s memorial service at Calvary Episcopal Church in New York City (planned by Pauli Murray), the officiating reverend inquired as to whether Pauli had ever considered being ordained. This was four years before the Episcopal Church, at its General Convention, voted to ordain women as priests. Yet Pauli was very much in need of spiritual healing and loved a challenge. So, after three years in seminary, she received a Master of Divinity degree on January 8, 1977, becoming the first African American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest and one of the first women to be ordained a priest.

The Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina has developed as an ongoing project a wonderful timeline of Murray’s life and achievements. The entry for February 13, 1977, is especially notable for capturing Murray’s reflections on this new calling:

February 13, 1977: Celebrated her first Eucharist at The Chapel of the Cross, at the invitation of the rector, the Rev. James Peter Lee. Read from the Bible that had belonged to her grandmother (Cornelia Smith), from a lectern that had been given in memory of the woman who owned Cornelia (Mary Ruffin Smith). This was also the first time a woman celebrated the Eucharist at an Episcopal church in North Carolina.

In her autobiography (p. 435), Pauli described her feelings at the Chapel of the Cross service as follows: “Whatever future ministry I might have as a priest, it was given to me that day to be a symbol of healing. All the strands of my life had come together. Descendant of slave and of slave owner, I had already been called poet, lawyer, teacher, and friend. Now I was empowered to minister the sacrament of One in whom there is no north or south, no black or white, no male or female – only the spirit of love and reconciliation drawing us all toward the goal of human wholeness.”

For the next seven years Murray ministered primarily to the sick in a parish in Washington D.C. Her ministry, and life, ended on July 5th, 1985, in my hometown of Pittsburgh. I, too, was raised in the Episcopal faith, and would have loved to have heard her sermons about ANYTHING.

In 2012, as the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina website explains, Pauli Murray was

named to Holy Women, Holy Men by the 77th General Convention of the Episcopal Church and thus became an Episcopal saint. According to her entry, “Growing up as a mixed-race person in the South, [Murray] became an advocate of ‘the universal cause of freedom,’ and throughout her life she worked tirelessly and with distinction as a lawyer, an advocate for civil and labor rights and feminism through her legal writings, essays and poetry.”

Pauli Murray’s official Feast Day is July 1st, and on or around this time each year, she is honored nationwide in the Episcopal Church with prayers, remembrances, and sermons in honor of her remarkable legacy.

The epic achievements of Pauli Murray will inspire generations of Americans to come. I was honored to be a guest on June 18, 2022, at the 10th anniversary celebration of Durham’s Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice.

Here is a description of the Center from their web site, followed by their bio of the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray which they graciously provided for the Durham Symphony’s April 10th Tribute concert at the Hayti Heritage Center.

The Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice

(https://www.paulimurraycenter.com/)

The mission of the Center is to lift up the life and legacy of the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray through programming about history, education, creativity, faith, and activism. The Pauli Murray Center’s goal is to address enduring inequities and injustices in our local, national, and global communities.

The Pauli Murray Center is a National Historic Landmark site, anchored by the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray’s childhood home built by their grandparents in 1898 at 906 Carroll Street. We invite you to visit to see our outdoor educational installation about Pauli Murray and the history of the house.

The Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray

A note on pronouns: Scholar Naomi Simmons-Thorne writes: “Given the rigid enforcement of the gender binary, we do not, nor will we ever know, [Pauli] Murray’s true gender identity.” To reflect this, this summary uses they/them/theirs, she/her/hers, and he/him/his pronouns interchangeably to refer to the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray.

Pauli Murray was born in 1910 to nurse Agnes Fitzgerald and educator William Murray in Baltimore, Maryland. After Agnes died when Murray was three years old and William’s mental health suffered, young Murray was the only one of their six children sent to live with Agnes’s family in Durham, North Carolina. William was eventually admitted to an African American mental hospital where he was later murdered by a white guard. Agnes’ sisters, Pauline and Sallie did their best to parent young Pauli Murray. In Murray they instilled a commitment to justice and equality.

Murray graduated from Hillside High School and then attended Hunter College, graduating in 1933 with a degree in English Literature. Throughout the 1930s, Murray actively questioned his gender and sex. He repeatedly asked physicians for hormone therapy and exploratory surgery to investigate his reproductive organs, but he was denied gender-affirming medical care.

In 1938, Murray began a campaign to enter graduate school at the all-white University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Despite a lack of support from the NAACP, Murray’s media and letter-writing campaign received national publicity.

Murray enrolled in Howard University School of Law in 1941 to become a civil rights lawyer. She was the only person perceived as a woman in her class and coined the term “Jane Crow” to describe the intersectional oppression faced by Black women. As a law student, they helped form the Congress of Racial Equality, took part in several restaurant sit-ins, and continued to wield their typewriter. For their final thesis, Murray wrote a paper outlining a new strategy for dismantling segregation and overturning Plessy v. Ferguson. This strategy later ensured the 1954 Brown v. Board win. In 1944, Murray graduated at the top of her class.

Murray completed their Master of Laws degree at the University of California with a thesis titled, The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment. Murray then served as California’s first Black deputy attorney general. In 1951, they published States’ Laws on Race and Color, which Thurgood Marshall described as the “Bible” for civil rights litigators. Murray enrolled in the Doctor of the Science of Law (JSD) program at Yale and became the first Black person to receive a JSD from Yale.

In 1956, Murray published Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family about the experiences of generations of their family members, early Durham history, and the impacts of white supremacy and anti-Blackness on their grandparents.

Pauli Murray joined Betty Friedan and others to found the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966, but later moved away from a leading role because s/he did not believe that NOW appropriately addressed the issues of Black and working-class women.

When Murray’s long-time romantic partner Irene Barlow died in 1973, Murray left her teaching position at Brandeis University to pursue a religious calling. In 1977, Murray became the first Black person perceived as a woman to be ordained to the Episcopal priesthood in the U.S. Murray died of cancer in 1985 and was buried with her aunts and Irene Barlow in Brooklyn, New York.

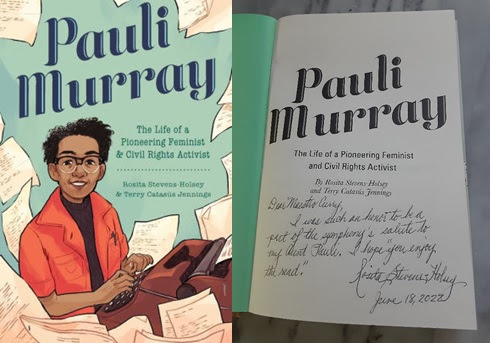

Celebrating 10 Years of the Pauli Murray Center—and Meeting Murray’s Niece

At the Pauli Murray Center’s 10th anniversary celebration, I was delighted to meet in person one of the honored guests of the event, Rosita Stevens-Holsey. Her mother was the youngest sister of Pauli Murray. Of this festive day, Rosita wrote, “We are all very excited to celebrate ten years of uplifting the legacy of my Aunt Pauli.”

Rosita Stevens-Holsey has been an educator, author, equal rights activist, and a home-refurbisher whose work has been featured in The New York Times, The Washington Post and Essence. Before our DSO concert that included my musical tribute to Pauli Murray ( “Love and Loss”), her niece granted me a fascinating hour-long interview about her famous aunt that we are pleased to share with you.

Here are some pictures from my visit to the celebration of the 10th anniversary of the Pauli Murray Center.

From left to right: C. Eileen Watts Welch (President of the Durham Colored Library, Inc.), William Henry Curry, and Rosita Stevens-Holsey

To gain a better understanding of the incredible legacy of Pauli Murray, great places to start would be Murray’s autobiography (Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage), the documentary My Name is Pauli Murray, and Rosita Stevens-Holsey’s 2022 biography, Pauli Murray—The Life of a Pioneering Feminist and Civil Rights Activist (of which I received an autographed copy!)

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Copy Editors: Suzanne Bolt and Tina Biello

Digital Layout and Publication: Tina Biello and Marianne Ward

Audio by Mark Manring

Thank you for being a important part of the Durham Symphony Orchestra family! We appreciate your support and vital impact on our community!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Ivy Community Service Foundation of Cary, Inc., the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and grants from the Triangle Community Foundation, The Mary Duke Biddle Foundation and the F. M. Kirby Foundation.