Monday Musicale with the Maestro – November 21, 2022 – Restore or Deplore? Reflections on “Cancel Culture” in Music

Monday Musicale with the Maestro

Dear Friends of the Durham Symphony Orchestra,

Monday Musicale with the Maestro. Restore or Deplore? Reflections on “Cancel Culture” in Music.

We are living through an era now where we are being challenged by ourselves and others to re-evaluate what we believe and why. This is reminiscent of the mid-to-late 1960s when old traditions were overthrown, and new ones took their place every day. This era included the push for Civil Rights, Women’s Rights, Gay Liberation, Black Power, and protest marches against the Vietnam War. The year 1968 also included one presidential candidate (Governor George Wallace of Alabama) who openly courted the white racist vote.

There is a Chinese curse that says, “May you live in interesting times.” Like that earlier period, our current decade has been “interesting” and filled with social and political upheavals. It’s again coaxed many of us out of our conformity and the hasty acceptance of norms and traditions. So we are again asking on every side, Which parts of our culture should be treasured and what should be trashed? Our most recent Durham Symphony concert asked that question about musical works, composers, and performers.

On November 5, 2022, the Durham Symphony presented A Concert of Canceled Music—by which we mean pieces (and performances) which, for political or social reasons, had been banned, boycotted, or kicked to the curb.

Our wide-ranging program of classical masterworks spanned a century of compositions, including works by Mendelssohn, Tchaikovsky, Ives, Florence Price, Prokofiev, Scott Joplin, and Aaron Copland, in addition to American folk and patriotic songs. The program also included a tribute to the African American contralto Marian Anderson, who was internationally famous for her repertoire, from classical works to spirituals. Her most famous concert was on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial (Easter 1939), after she was refused the venue at Constitution Hall because of her race. The brilliantly gifted soprano Jemeesa Yarborough evoked the moment with two selections from Anderson’s actual program that day: “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” and “My Soul Been Anchored in the Lord.”

As a gesture of solidarity to the people of Ukraine, we also included on our concert the Ukrainian national anthem and the 2nd movement of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 2 (“Little Russian.”) To some, in this year, the choice of Tchaikovsky might seem controversial—and on the surface, it might not be clear how this was a tribute to Ukraine. Putin’s horrific Russian attack on Ukraine is the most recent eruption of a lingering imperialism that plagues and threatens civilization itself. And this year, some have desired to cancel all things Russian, though Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 2 reflects his own admiration for Ukrainian culture. “Little Russia,” was a nickname for Ukraine, and Tchaikovsky (who was staying there at the time) has enshrined several of its lovely folk songs in the symphony. The subtitle was not Tchaikovsky’s own idea, but a nickname that was given to the symphony by a friend. Yet the name has been off-putting to some in classical music circles this year, and there has been a suggestion to rename it “Ukrainian” if it is to be performed at all!

But all this was prelude to the most complex and controversial piece on our November 5th program– a work by a composer born in Ukraine but viewed by some (ironic as this is) as an “official” artist of the Soviet state: Sergei Prokofiev. In my view, he is one of the greatest melodists of the 20th century, and for this reason, he has been one of my “soulmate” composers for many years. I’m especially a fan of his three evening-length ballets: Romeo and Juliet, Cinderella, and The Stone Flower.

The work by Prokofiev featured on our concert was Zdravitsa (A Toast), Op 83. It is a twelve-minute cantata for chorus and orchestra that was commissioned to honor the 60th birthday of Joseph Stalin and was premiered on his birthday, December 21st, 1939. In the Soviet Union, Prokofiev’s piece was given the startling nickname “Hail to Stalin.”

Can you imagine? HAIL TO STALIN??!!

Some music historians whom I admire would argue against this piece EVER being performed, especially while another Russian tyrant, Vladimir Putin, is waging a terrible war against the separate nation of the Ukraine and wreaking havoc on his own people in the process. So, beautiful melodies aside, why did I program this work? And what case can be made for it surviving in some form? My answer requires some background.

Prokofiev was an international celebrity as a composer and pianist by the time he was in his mid-20s. He made concert tours of Europe and America as a pianist and was a thoroughly cosmopolitan citizen of the world. But he was frequently homesick, and the urge to return to Mother Russia was strong in him. As early as 1932, he considered returning to his homeland with his wife Lina and his two sons. But as he was weighing his decision, he was hearing rumors of new Soviet restrictions in artistic and political policies and that to defy Stalin was to risk your career, or even your life. This era is known as “The Great Terror,” a time when anyone objecting to Stalin’s policies could suddenly disappear–usually into a labor camp or a grave.

The rumors were terrifying—and Prokofiev’s wife Lina (who had been born in Spain) did not share her husband’s longing to return to Russia. But Stalin’s emissaries insisted that Prokofiev would not be treated like an “average” comrade. He would be guaranteed a handsome yearly fee writing music for this new republic that was eager to show the world the high quality of Soviet culture. It seemed like too good an offer to refuse. Lina reluctantly agreed, so they relocated their family there in 1936.

Prokofiev was fully aware that he would be expected to compose works that celebrated the strength of the nation, depicting it as full of promise and opportunity for all. In an attempt to prove his allegiance, he wrote an opera celebrating the Communist “common man.” It was inspired by a book titled I Am a Son of the Working People. The titular hero is Semyon Kotko, a Ukrainian soldier serving in WW I. Prokofiev was thrilled when his close friend and favorite artistic colleague, the famous stage director Vsevolod Meyerhold, reached out to him to stage the premiere of the opera. Meyerhold had directed the premieres of other Prokofiev operas, and the composer trusted his artistic judgment. Little did he imagine the dangerous alliance he had just made!

While Prokofiev was finishing his opera, he was asked to write music for a series of athletic games being “choreographed” by Meyerhold. But when he completed the music and attempted to contact Meyerhold about their next steps on the project, he received no replies. Prokofiev was worried to learn that none of their mutual friends and business colleagues knew where Meyerhold was either. Only years later did they discover that their friend had been arrested as a spy and executed by a firing squad.

Meyerhold had an independent mind, and in private and public he vigorously complained about the policies of Socialist Realism in the arts. The main tenets of this policy centered on portraying an ideal future with a united citizenry and loyalty to the Communist party. Many, including Meyerhold, believed that this strict system choked off creativity and led to uninspired works that were mediocre at best. In June of 1939 he gave a notorious speech where he held nothing back about his distaste for artistic censorship. For Meyerhold to show such courage in the face of a brutal government was incredibly brave–and naïve. But he must have felt safe because of his considerable national fame. He was a household name at the time, something of a Soviet Steven Spielberg. However, a few days after his speech, he was arrested. Soon after, his wife was murdered by thugs sent by the government to ensure her silence.

During the next four months, the imprisoned Meyerhold was interrogated every day and beaten so severely for hours at a time that eventually he could no longer walk. Finally, just to put an end to his torment, he signed a “confession” that he had been a spy, leading to his execution on February 1, 1940. His death was not in the newspapers, and what happened to Meyerhold remained a state secret until the mid-1950s. The Prokofievs’ terrified reaction to this can only be imagined. They must have pondered who would be the next to disappear.

They also must have wondered whether Meyerhold was led to say under torture that they, too, were spies—or at least shared his dangerous views. The government soon let Prokofiev know quite directly that he, too, was unsafe. The music Prokofiev wrote for the athletic exhibition was abruptly canceled, and the Prokofievs’ passports were revoked. The composer would never be allowed to do the European concerts that had been promised him.

I recount the story of Meyerhold to give context to what happened next. Three months after Meyerhold’s disappearance, Prokofiev was commissioned to write a cantata celebrating the 60th birthday of Stalin. The text was chosen for Prokofiev, and he was offered a large sum of money. Supposedly the text was derived from folk poetry, but most of it was doggerel produced by the committees that wanted to emphasize the “greatness” of Stalin. Most of the text extols the beauty of Mother Russia, but there are a disturbing number of lines that are horrifying in their abject fealty to the monster that was Stalin.

It is easy to judge Prokofiev negatively for writing a work for money in honor of a human aberration. But keep in mind the plight of the Meyerholds and the revocation of his passport. Prokofiev desperately wanted to secure the safety of himself, his family, and his art. So he took a deep breath and began writing a piece for Stalin’s birthday. It is a measure of his professionalism and emotional detachment, that once undertaken, he resolved to write a masterpiece—even if it was commissioned in honor of a criminal responsible for the deaths of 20 million Russians. In Notebooks and Conversations, the legendary Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter (a friend of Prokofiev) calls Zdravitsa “one of his very finest compositions. . .a work of genuine inspiration” (89). He goes on to say,

the piece is absolutely brilliant. A monument, it’s true, but a monument to himself, to Prokofiev! He wrote it with a kind of insolence, a noble amorality: ‘Stalin? Who’s that? But yes, why not? I can do anything, including this sort of “thing.” For him, it was a question of writing music, and that was something he knew how to do. (42-43)

As far as the music of A Toast, I whole-heartedly love it. For obvious reasons, it’s rarely played anywhere in the West. But its controversy lies in its words, not its music. The lively melodies resemble Russian folk music. And it begins with an extraordinary melody that has been called by a non-partisan listener “one of the fairest and noblest melodies in all music” (Daniel Jaffe, Sergey Prokofiev 159). See what you think of this version with English subtitles.

Zdravitsa, Op. 85, “Hail to Stalin” (Original Version)

Valeri Kuzmich Polyansky, Russian State Symphony Orchestra

PIAS (on behalf of Chandos); LatinAutorPerf, and 3 Music Rights Societies

It would be nice to relate that the composition of Zdravitsa did indeed secure the safety of the Prokofiev family. But in fact, worse was yet to come.

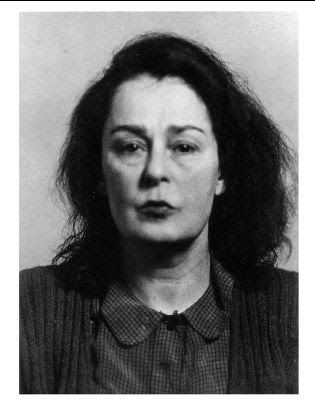

Sergei had told his wife that if she wasn’t happy in the Soviet Union, they would move to Paris, but he reneged on that promise. And to add insult to injury, he divorced Lina and left her and his two teenage sons to live with his student and mistress, Mira, who was 20-years younger. At this point, Lina became desperate to leave Russia. She began going to foreign embassies to see if she could get her passport re-instated. Unfortunately, this was noticed by the Soviet authorities, who then considered her to be a disloyal citizen. Then came the catastrophe: she was arrested on trumped-up charges of being a spy. A day or two later, a group of Soviet policemen broke into her home looking for evidence that she was a traitor. They took valuables, including the piano, and put everything they wanted in garbage bags to be dragged down a flight of stairs. The two teenaged sons arrived home a few hours later and were shattered by what they saw–and what they did NOT see: their mother.

The frightened boys took a night train to Moscow and walked nine miles through the snow-covered streets to tell their father what had happened. One can only imagine how guilty the composer felt then about his decisions to stay in Russia and to leave his wife and sons. Several days later they found out that Lina had been arrested, tortured, and sentenced to twenty years hard labor in a prison camp in the Gulag. Somehow, she managed to preserve her mental and physical health.

One day, four years after her arrest, a fellow prisoner told Lina that her husband had died the week before. The news had been delayed because, in an ironic twist of fate, Stalin had died within hours of Prokofiev’s passing. There were no flowers available for the composer’s funeral because they all had been used for Stalin’s.

Three years later, at the age of 59, Lina was allowed an early release and was reunited with her sons. It is hard to believe that this was the family life of the composer who wrote the most famous musical work for children, Peter and the Wolf.

My understanding of “The Great Terror” and the Prokofiev family’s precarious place within it has been deepened considerably by two of Simon Morrison’s books on the topic, both of which I recommend highly for further reading. They are The People’s Artist: Prokofiev’s Soviet Years (Oxford University Press 2010) and The Love and Wars of Lina Prokofiev: The Story of Lina and Serge Prokofiev (Harvill Secker 1959).

On the 50th anniversary of the premiere of Peter and Wolf, Lina took the speaker’s role in a performance in New York City. And in 1986, three years before her death at the age of 91, she recorded it. Below is an excerpt from that priceless performance—and a photo of her celebrating her 91st Birthday with her sons.

Peter and the Wolf, Op. 67: I.

Introduction by Lina Prokofiev

Royal Scottish National Orchestra

Provided to YouTube by PIAS

Whither Zdravitsa?

Various attempts have been made to salvage Zdravitsa from the dustbin of history. The quality of the piece as music has never been questioned. The sticking point has always been the text. In the mid-1950s, when the omnipotent image of Stalin was banished by the Soviet government, the text was changed to eliminate all references to him. There have also been English versions of this piece that delete all the references to Stalin.

Because of my considerable affection for this work by one of my favorite composers, I hit on the idea of writing a version for orchestra alone: no chorus, no text, no allusions to Stalin. Before I undertook this “rescue project,” I knew I had to receive permission from the Prokofiev estate to do it. After some considerable back-and-forth, they agreed that I could proceed with the transcription and my single performance—though I waived editorial credits for a new “arrangement.” And the recording of the performance is restricted for review by the Prokofiev estate alone, so we cannot bring it to you here. But the project itself was truly inspiring.

I understand that some would question the ethics of my transcription. I cannot know whether Prokofiev would have approved or disapproved of what I did. However, the standard repertoire has many such transcriptions that are accepted, including Maurice Ravel’s glittering orchestration of Mussorgsky’s work for piano, Pictures at an Exhibition.

Others might argue that the piece should not be softened by changing or deleting text which praises a vicious criminal. They might argue that it should be allowed to stand, like a Confederate statue in a town square, to REMIND people of past evils now transcended.

But if Prokofiev had written this masterpiece as a sincere tribute to Stalin, it would not have so moved me. Prokofiev’s context while writing this work is important. And it seems to me that his intent was never to glorify a monster. But I must admit—a terrible confession—that I would NOT have performed an equally thrilling work by ANY composer—regardless of context– if its title were Hail to Hitler or A Toast to the Ku Klux Klan!

This dichotomy in my thinking is an unnerving thing to recognize. But such honesty might be useful for us all in approaching the topic of canceled art and wading through difficult choices regarding what to keep and what to toss. I admit that I do not react to the name or sight of Stalin as I do to the mention of Hitler or the sight of a burning cross. This sobering realization leads me to understand the fact that many Southern whites see in a statue of Robert E. Lee something different from what I see. Circumstances, community, and conformity rule even our supposedly “objective” thinking—which is for all of us based more on feeling than we would like to admit. Unless we can understand and accept this immutable aspect of human nature, it will be all too easy to quickly demonize those who seem to disagree with—or otherwise “trigger”—us.

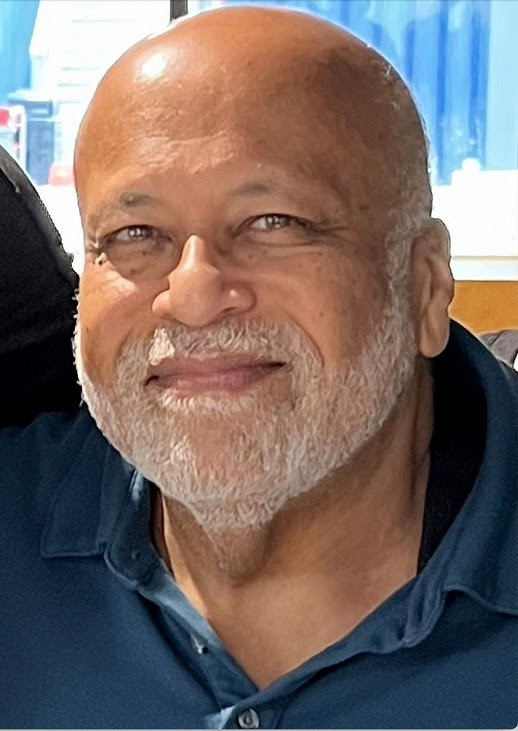

My personal feelings about “cancel culture” relate to broader issues that have been a constant companion of mine since I was ten years old and saw in Virginia white and colored drinking fountains. Similarly, the trauma of being called a “genetic mistake” when I realized I was gay. I have tried to be vigilant lest I return such hate and thus destroy myself. I have tried to understand, to empathize—as here, with Prokofiev’s creation of Zdravitsa.

For many in the orchestra and the audience, our performance of Zdravitsa was one of the highlights of our Concert of Canceled Music. I was thrilled to bring before new audiences a fresh perspective on this buried musical treasure.

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Copy Editor & Digital Layout: Tina Biello & Marianne Ward

Thank you for being a important part of the Durham Symphony Orchestra family! We appreciate your support and vital impact on our community!

Funding is provided (in part) by the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources), and grants from the Triangle Community Foundation, and The Mary Duke Biddle Foundation.