Monday Musicale with the Maestro – October 14, 2024 – American Composer Roy Harris: “Enemy of the People” or American Icon?

“Whenever American music is discussed, the name of Roy Harris comes to the fore. America is rich in musical talent, but Roy Harris has in the hall of American music a place which is unique. He has a natural gift for the melodic line, and his melodies are in some uncanny way reflective of the American scene without being literal quotations.”

– – Musicologist/Conductor Nicolas Slonimsky, Christian Science Monitor, February 27, 1943.

“The music of Roy Harris soars to heights seldom attained by any other composer.”

– – Composer/Conductor Howard Hanson, “The Flowering of American Music,” Saturday Review, August 6, 1949, 162.

“His is the most personal note in American music today.”

– – Composer/Conductor Aaron Copland

——————————————————–

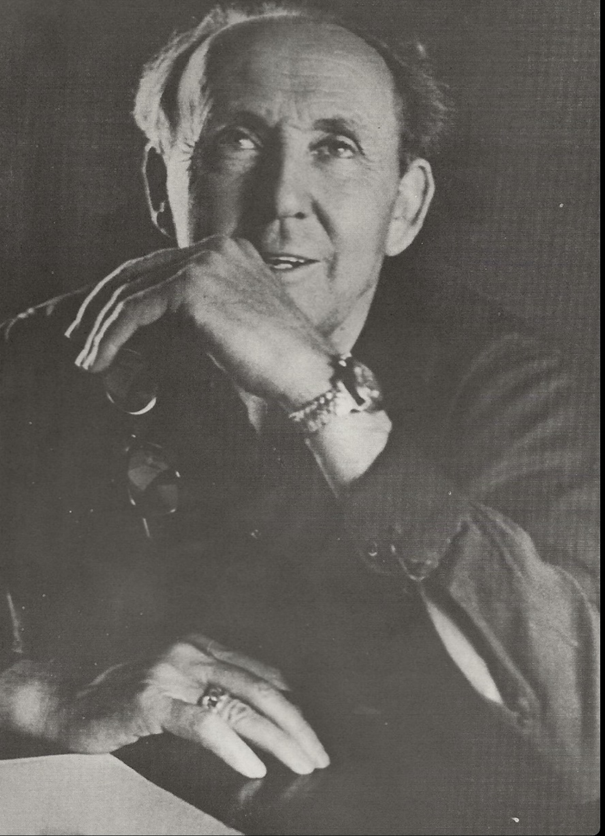

Those quotations from three of the greatest musicians of the 20th century summarize my considerable love for the music of Roy Harris. Harris had the unteachable gift of being able to compose a compelling, expressive melody. His music is so personal that it can be recognized as his in only a few bars. These musical inspirations derive from the mysterious alchemy of rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic elements that cannot be analyzed with mathematical certitude. And his music really does soar with an optimistic, other-worldly, and visionary quality that makes him for me the American Bruckner. I often refer to Bruckner as being God’s symphonist, and I hope this helps to explain my reverence for the music of Roy Harris.

My love for his music dates back to my mid-teens when I discovered his Symphony No. 3. From its 1939 premiere, this work has been popularly known as THE great American symphony, and Harris himself bears a uniquely American stamp—even in his origins! He was born in a log cabin on Abraham Lincoln’s birthday in Lincoln County, Oklahoma. And yes, like me, he was obsessed with Lincoln. At least eight of his works were inspired by the legacy of our 16th president, and I hear in those pieces musical depictions of Lincoln’s eloquence, his deep seriousness, and his unbridled (sometimes vulgar) sense of humor. One of these works is Harris’s Symphony No. 6 (“Gettysburg”), inspired by Lincoln’s most famous speech. The first movement, “Awakening,” will be featured on the Durham Symphony’s October 20, 2024, concert at the Hayti Heritage Center. The DSO and I first performed the final movement of this work, “Affirmation,” at a Martin Luther King Tribute concert at Duke University several years ago. Here is a link to that performance!

I have conducted Harris’s 3rd Symphony with the National Symphony Orchestra, the Baltimore Symphony, and the Atlanta Symphony. My first time was with the National Symphony in September 1979, at Washington D.C.’s Kennedy Center. Harris’s symphony was the major work on an All-American program, and a month before the concert, NSO administration told me that they’d invited all the featured composers to the rehearsal and concert! I was thrilled for the opportunity to meet them all—including the African American composers George Walker and Adolphus Hailstork, both of whom attended. Unfortunately, Harris was not there, having been hospitalized after a bad fall. The performance of his symphony went well, and I was disappointed that he could not hear it. I was distressed when—only a month later—he passed away at the age of 81. His biographer, Dan Stehman, told me a few weeks later that I was the last conductor to perform “The Great American Symphony” while its composer was alive.

Stehman appreciated my fervent enthusiasm for the music of Harris and gifted me with a large box of material about other Harris works that he thought I should look into. In the years since, I have conducted symphonies 4, 5, 6 and 7 and his “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” Overture. Dan Stehman and I kept in touch until his untimely death in 2001, and my study of Harris’s work has been ongoing.

This past June, I spent the entire month reexamining the works of Roy Harris, especially the 5th Symphony. I recently added to my library two Harris bios by Dan Stehman: Roy Harris: An American Musical Pioneer[1] and Roy Harris: A Bio-Bibliography. [2] These have been invaluable in my getting closer to the music and the man. I was moved to discover that Harris had been a lifelong advocate for African American equal rights. Stehman notes, for instance, that while preparing for the Cumberland Forest Festival, Harris was stunned to find out that one of the co-sponsors (the University of the South) had refused to admit African American students to their School of Theology. Outraged, Harris organized a mass resignation of the festival’s faculty (Roy Harris: A Bio-Bibliography 13). Through the years, Harris’s social activism led him to join many progressive groups advocating for social justice and world peace. Unhappily, however, his altruism triggered a dark period in his life that tested his idealism: Harris became a victim of the “red scare”—the McCarthy Era in America.

Roy Harris Branded as a Communist

Many forget that during WW II, the Soviet Union had been one of our allies in the successful effort to rid the world of Hitler and fascism. Soon after the war ended, however, the Soviet government began to control several of the central European nations. As Winston Churchill put it, “An iron curtain has descended over Europe.” This betrayal by Stalinist Russia was made worse by the nuclear arms race that led both nations to the potential for mutually assured destruction. As if this weren’t bad enough, unscrupulous politicians on both sides created career advances for themselves by attacking individuals seen as being disloyal. For instance, Republican Richard Nixon first came to national attention in the 1950 California Senate race by branding his Democratic opponent, Helen Gahagan Douglas, as a “pink lady”—a Communist sympathizer. As journalist Colleen M. O’Conner notes, this was untrue. But as Nixon’s campaign manager, Murray Chotiner, saw it, “‘The purpose of an election is not to defeat your opponent, but to destroy them.’”[3] Nixon won the election handily, and his career took off. Two years later he was Vice-President, and Douglas’s political career was in ruins.

Deceptive tactics like these were part of “the Joseph McCarthy era,” named after the Republican senator from Wisconsin whose fabrications about an America overrun by “leftist traitors” fed America’s fear and paranoia about Soviet Russia. During this period, the careers and lives of the accused were often destroyed by lies and insinuations. Playwright Lillian Hellman eloquently called this era “Scoundrel Time.”

Despite the risk of being ostracized and demonized, many Americans felt that the only way to ensure that the world would avoid annihilation by nuclear warfare was to lobby for peace and friendship with Soviet Russia. Harris was one of those people. During WW II, his activities included being the vice-chairman of the National Council of American-Soviet Friendship, and some of his compositions were inspired by these activities, including an orchestral work titled Ode to Friendship and his 5th Symphony, which bore this dedication to “the heroic and freedom-loving people of our great Ally”:

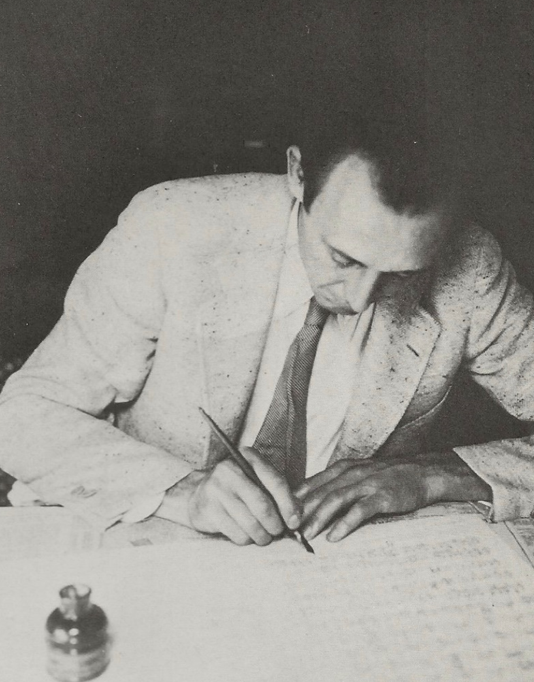

As an American citizen I am proud to dedicate my Fifth Symphony to the heroic and freedom-loving people of our great Ally, the Union of Soviet Socialist republics, as a tribute to their strength in war, their staunch idealism for World peace, their ability to cope with materialistic problems of world order without losing a passionate belief in the fundamental importance of the arts. (Dan Stehman, Roy Harris: A Bio-Bibliography, 151)

Harris at work on his 5th Symphony.

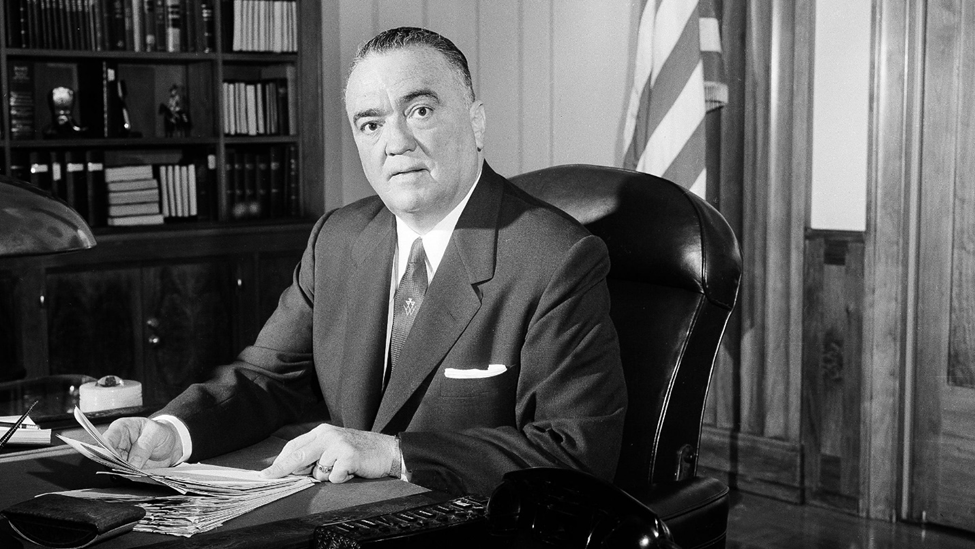

But as early as 1944 these activities by Harris sounded suspicious to some, including J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI.

From 1943 to1945, Hoover launched a full investigation of Harris’s patriotism or lack thereof (Mulcahy 414). [4] The material they turned up included his membership in left-wing groups like Progressive Citizens of American and the aforementioned National Council of Soviet-American Friendship. They also found him to be a liberal Republican, an Episcopalian, and a member of the Rotary Club. Harris—unaware of this background check—was cleared by Hoover and the FBI. And there the matter rested until 1949 when Harris’s former employer Dr. Franklin R. Harris (no relation) received an ominous letter from a WW II veteran named Robert Donner. Dr. Harris was the President of the Utah State Agricultural College, and the letter-writer had become director of a bank in Colorado Springs.[5] Donner’s letter came out of the blue and still makes for harrowing reading:

“Roy Harris is a red,” Donner wrote,

and his wife, who may be OK, is dominated by him.…The mere fact that Harris had been approached by the Soviet Union to make a tour through that country is significant. His statement that he is against communism does not mean that he is not Communist, or a sympathizer, or a socialist. There is little difference between the two. A Communist is simply a Socialist in a hurry. They both have the same end in view. A Communist is trained to lie, deceive, undermine, subvert, etc. in the interests of the Party. I want to follow this matter through our Colorado senator and the Department of Justice. People like this should be exposed and I have enough to do just that. (Robert Donner. August 31, 1949)[6]

Notice that Mr. Donner mentions no specific charges.

Dr. Franklin Harris responded to Donner with shock and tactfully worded outrage:

You indicate that you believe Roy Harris Communist. I think you are entirely wrong in this matter. I believe I know a Communist when I see one, at least when I have an opportunity to be with them. I am well acquainted with the Communist techniques. I have had many conversations with Dr. Harris on this subject. It is true that he and his wife were invited for a concert tour of Russia. However, before the final arrangements were made, they asked about Dr. Harris’s attitude toward the Communistic doctrine. He told them he was not in sympathy with the doctrine of Communism, and as a result, the offer for giving this tour was withdrawn. I have no idea what your purpose is in persecuting Roy Harris. I suppose this is a matter of your own, but I, myself, have found him to be a very fine gentleman and an outstanding musician. (Franklin R. Harris. September 2, 1949.)[7]

In doing research on this incident, I could not find if Harris was made aware of this dialogue. Perhaps not. But in 1951, he became embroiled in accusations such as these which could have ended his career.

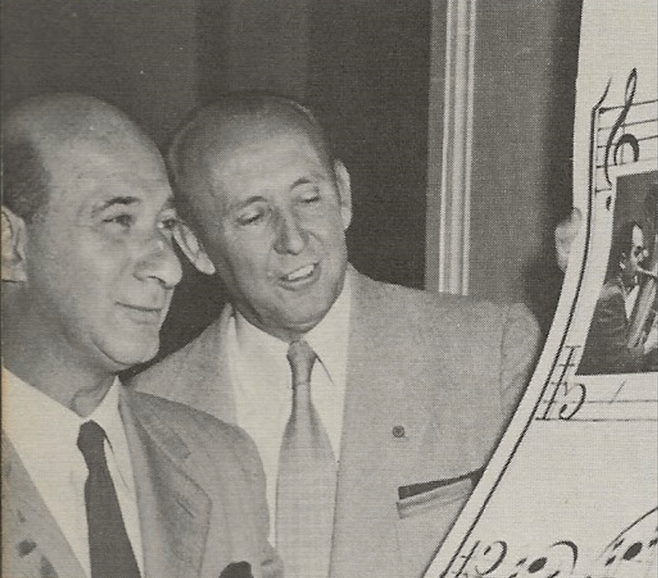

In 1951, Harris and his family moved to my hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He was there to teach at the Pittsburgh College for Women (now known as Chatham College). At this time, Harris was the director of the ambitious Pittsburgh International Contemporary Music Festival that would include a performance of Harris’s Symphony No. 5 by the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra and its Music Director, William Steinberg.

Conductor William Steinberg with Roy Harris

As described by Richard P. Mulcahy’s superb article “The Justice, the Informer, and the Composer,” events then took a sinister turn. I am deeply indebted to this article for my understanding of this period in the composer’s life.[8]

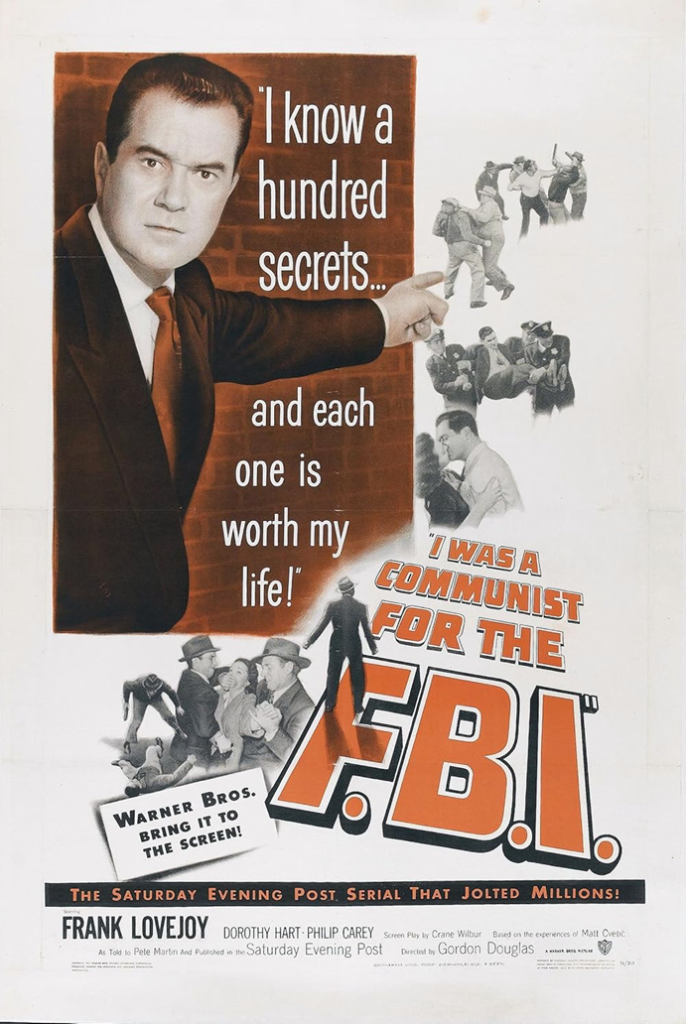

Matthew (“Matt”) Cvetic

As Mulcahy explains on pp. 409-420, Matthew “Matt” Cvetic was a paid informant for the FBI from 1943 to 1950, and his job was to identify Communist sympathizers in southwestern Pennsylvania. He was helpful to the FBI but was also an unreliable and erratic alcoholic who had been arrested for beating his sister-in-law. After a drunken incident when he threated to shoot a woman in his hotel room and bragged about being an FBI undercover agent/counterspy, Hoover fired him. His dismissal by the FBI had not been made public, however, and on February 21,1950, he appeared in front of Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Cvetic named the names of 290 Americans who he described as being Communists—some of whom were fellow confidential informants. This led to his becoming a national hero to some, and he basked in the limelight as a lecturer across the country. His fabricated exploits became well-known through a series of articles in the Saturday Evening Post, called “I Posed as a Communist for the FBI.” These stories became so popular that they became the basis for a radio serial—and in 1951, Warner Brothers produced a feature film titled I Was a Communist for the FBI.

The FBI was unamused by these fictionalized concoctions but remained silent about them, and around this time, Cvetic met Michael Musmanno, a judge with political ambitions.

Michael Musmanno

Although, by the end of his life, Musmanno was admired by many for his scholarship and his sympathy for the working man and civil rights causes, he could at times be a combative, publicity-hungry showman. Then, as now, a good way to get public attention was to make loud denunciations about a political opponent. (I am reminded of the media motto “If it bleeds, it leads.”) Supplied by inside information from unknown sources, Musmanno and Cvetic joined forces to “out” Roy Harris as a “Commie pinko.”

Their first attack occurred at the annual state convention of the Pennsylvania American Legion in Philadelphia on August 7, 1952. Cvetic’s opening statement included a sarcastic attack on academic freedom: “In the great debate on Communism, should our schools and colleges be used as sanctuaries for irresponsible teachers and employees who give their support to un-American causes? The answer is a resounding No!” Cvetic then mentioned Roy Harris and his controversial dedication of his 5th symphony. For Cvetic this could perhaps be overlooked if “Harris had dropped his pinko associations when the Russian myth was exploded.” But he went on to say that Harris was still involved with progressive institutions that were merely Communist fronts.

But what really offended Cvetic was that this “fellow traveler” had been awarded a gold baton by the West Point Academy. For Cvetic, that Harris should receive a positive citation from America’s most famous school for our future servicemen was “a national disgrace.” He concluded his remarks by saying, “I have already sent Dr. Harris an advance copy of this address. Like all Pennsylvanians, I await an answer!”

The next day Pittsburgh papers reported the speech. Roy Harris was interviewed and was more amused than angry, insisting that his patriotism was beyond question. The headline of the Pittsburgh Post Gazette read, “Composer Laughs Off Charges.”

But Cvetic dug in and gave a speech in Pittsburgh on August 26, 1952. He added additional charges including that Harris had committed the “sin” of sending an enthusiastic and approving telegram to the Soviet composer Dimitri Shostakovich when he was in a New York City for the “Social and Cultural Conference on World Peace.”

Things were getting more serious.

Mulcahy observes,

Clearly, with regard to Harris, someone was out for blood. Was it Cvetic, or was he fronting for someone else? While there is no hard evidence that Cvetic’s speeches were ghost-written, an FBI staff member who attended a Cvetic presentation claimed it was obvious Cvetic’s remarks had been prepared for him.[9]

Now Harris was deeply concerned. He went to the Pittsburgh branch of the FBI to speak to the head. Harris laid out material that proved both his loyalty and Cvetic’s lies. He asked the FBI to clear him.

However, Musmanno was just warming up. He brought up Harris’s dedication of his 5th Symphony to the peace-loving Soviet people and pointed out that removing the dedication would be a simple solution to the problem. After all, he reasoned, hadn’t Beethoven removed the dedication of his “Heroic” Symphony (“Eroica”) to Napoleon when Napoleon abandoned his republican principles and crowned himself Emperor of France? However, Harris refused to do this, seeing it as an admission of guilt for embracing peace and brotherhood.

All this was going on while Harris was already under pressure as Director of the Pittsburgh International Contemporary Music Festival, the climax of which was going to be a performance of this 5th Symphony! On the morning of the evening performance of his work, Musmanno urged the audience (via a newspaper interview) not to applaud at the conclusion of the 5th Symphony. Harris and the performers must have been extremely worried that night that there might be boos and loud threats mixed with the deafening silence of withheld applause. However, none of that happened. The work received a rapturous ovation which can be heard in a “live” recording of the piece. And the smile on Harris’s face as he stepped onstage to accept the ovation is poignant, especially considering its context.

This public success repudiating their views was galling to Musmanno and Cvetic. Two days after the festival ended Musmanno asked HUAC to investigate Harris. To bolster his claims, Musmanno sent McCarthy and the other committee members Cvetic’s two speeches and his condemning material about Harris.

But at this point, members of the Pittsburgh community began to raise their voices in protest against the negative antics of Musmanno and Cvetic. In early December 1952, David Lawrence, the mayor of Pittsburgh, announced that he was backing Harris in this feud: “We have heard a lot about guilt by association. This is the first time that we deal with guilt by dedication.” (Mulcahy 422)

A few months later, Cvetic argued that since Harris would not remove the dedication, he was thus honoring “the people of the Soviet Socialist Republic, the same Soviet force whose bullets are continuing to kill American boys in Korea.” Musmanno censored Harris for continuing to dedicate his 5th Symphony “to a country which to date is responsible in Korea for over 126, 000 American casualties” (Mulcahy 421).

Harris then issued a statement expressing his belief that until now, he thought that the American government had created laws to protect its citizens from being harassed for speaking one’s mind. “I was born an American,” he said. “I have always done and will continue to do the best I can to honor and protect this country. As a patriotic duty, I did what I could to aid our common cause with Russia. That we have since found our philosophies and program to be incompatible is no reason to challenge my loyalty or that of anyone else” (Mulcahy 422).

At this point, the FBI began taking a careful look at what was happening in Pittsburgh. On December 12, 1952, an FBI special agent reported to J. Edgar Hoover, saying that Cvetic and Musmanno had been lying about Harris, “with miserable results.” The Pittsburgh branch of the American Legion then offered to break this stalemate by sponsoring an informal hearing with the principals in this dispute. The meeting lasted for two hours, and the breaking point was reached when Harris and Musmanno began hurling insults at each other. The committee then adjourned to discuss their conclusions.

Finally, after some of the most grueling months of his life, the clouds started to dissipate around Harris. His employer, the Pittsburgh College for Women, proclaimed his innocence, and on March 3, 1953, the Americanism Committee of the American Legion exonerated Harris, saying that he was indeed a loyal American citizen. Relieved but still angry, Harris issued a statement that the attacks on him were “vicious” and “unwarranted” and that “the effrontery of Cvetic and Musmanno was equaled only by their lack of principle” (Mulcahy 428).

The Aftermath

“In spite of his vindication,” Dan Stehman writes,

Harris was bitter and irascible for a long time afterward. The sorry incident seems to have been one of the major events in his life that impinged on his nostalgia and idealized vision of a rural America. Though his perpetual optimism was not stifled for long, events such as these troubled him deeply and forced him to confront some of the realities of life in America at mid-century. (Roy Harris: An American Music Pioneer 102).

I recently interviewed Bradley Cawyer, perhaps the greatest living scholar on the life and music of Roy Harris. He told me, “Harris not only took this horrifying incident personally, it also damaged his faith in this country and its unceasing upwards curve toward equality and justice for all.”

We often think of the Arts as somehow rising above American politics and not being affected by social controversy. Not so! May I recommend to you my Monday Musicale detailing the experience of the beloved and iconic American composer Aaron Copland with the HUAC and Joseph McCarthy: “Canceling Copland. Politics and Censorship in the Cold War Era.”

The great American composer-conductor Leonard Bernstein was a relentless advocate for progressive political causes. This led to many incidents that aren’t generally known, including his blacklisting by the State department in 1950, being investigated by the FBI, the temporary cancellation of his passport, and the Nixon administration’s attempts to undermine his political activities.[10] The Red Scare era also included its “Lavender Scare”. In the 1950s McCarthyite supporters also worked to expose closeted gays who worked for the U.S. government. And this soon extended to prominent cultural leaders. Many of our arts heroes of that time were terrified that they would be publicly condemned for being gay or bisexual, including Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins, and Tennessee Williams.

It’s heartening to discover that Roy Harris’s progressive views were not silenced by his harrowing experience in Pittsburgh in the early 1950s. During the Civil Rights era of the 1960s, he spoke frequently about the plight of African Americans who had waited over a century to be assured of their equal rights. And several of his compositions alluded to this—including, most controversially, his “Bicentennial Symphony” (Symphony No. 13). This work was commissioned by the National Symphony Orchestra for a 1976 premiere at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. A glittering and bejeweled audience gathered that night expecting to hear a joyous and patriotic musical celebration. Instead, they heard a work for chorus and orchestra with text featuring loud denunciations of the Confederacy and opposing voices saying in the 3rd movement, “Fight, fight, fight for the right to keep our slaves!” (Stehman, Roy Harris: An American Musical Pioneer 146).

The reviews were mixed, as Dan Stehman reports on page 312 of Roy Harris: a Bio-Bibliography. Robert Strassburg (writing for the University Times at California State University, Los Angeles), titled his review “Symphony Blasts American Black Suffering.” Here, he asserted, was “a granitic work. . . unflinching in its forthright denunciation of the treatment accorded black people during the past two hundred year. . . “Black History Week found its music champion in. . . .Dr. Roy Harris. . . (qtd. in Stehman 312). It was, he wrote, an “epoch [sic] choral ode demanding that the blessings of liberty and equal justice under law be extended to all.” Noting the mixed reactions of the audience—from “excited appreciation. . .to polite rejection”—Strassburg observed that Washington critics and some patrons “found the theme of the Symphony traumatic in its powerful evocation of a shameful part of our historic past” (qtd in Stehman 312).

Only a week before, in fact, Paul Hume (of the Washington Post) had described the experience as the “Symphony’s Unsettling Evening,” calling the work itself “a caricature of music. . .with appallingly puerile content.” Reacting to this, perhaps, Strassburg concluded that “Washington critics… were unsettled by what they felt was a ‘fearsome and unfriendly’ approach to the course of events in the United States during these past 200 years.” George Gelles of the Washington Star found the work flawed and “childlike” concerning “belief in the moral purpose of music,” yet he found that personal aspect of the work “touching” and “impossible to ignore” and reflected on Aaron Copland’s favorable assessments of Harris (qtd in Stehman 312)—a view shared by many of his fellow American composers and expressed also in the opening quotations about Harris that I shared with you.

I regard Harris as a true patriot and a luminary of American musical art, and I hope that you will come to the same conclusion.

As we near the end of this turbulent and polarizing election season, the DSO and I hope that our October 20th concert at the Hayti Heritage Center will be a joyous, even festive, reprieve from strife —a celebration of our shared love for American orchestral music from a richly diverse array of composers. We have given our program the title The Promise of America. It’s a phrase that means different things to different people. For me, it has always meant that America (despite setbacks) has been an ever-improving country that is gradually but inexorably struggling towards fulfillment of its creed that “all people are created equal.”

That very phrase from Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address inspired the opening movement, “Awakening,” from the Symphony No. 6 (“Gettysburg”) by Roy Harris, one of the works to be performed on our concert. We will also feature music by Aaron Copland, Morton Gould, and Richard Rodgers. Two of our featured composers were African American, Florence Price and William Grant Still. Both were born barely 50 years after the end of slavery and reached adulthood in a country where many saw them as something of a “problem” because of their race. However, my life has been different from theirs. I was born one month after Brown vs. Board of Education, and in my lifetime, I have seen enormous strides towards “liberty and justice for all”—including the legalization of interracial and gay marriage, the first female presidential candidates, and the first African American president and vice president. Though none of these progressive advances occurred without conflict or controversy, it is my personal belief that we owe it to our ancestors, ourselves, and those who come after us to embrace faith and optimism as we fulfill the Promise of America.

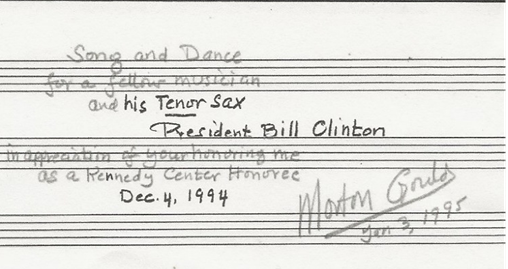

Another exciting feature of our October 20th program will be the world premiere of Morton Gould’s Song and Dance. This work was composed in 1995 as a gift for President Bill Clinton to play on his tenor sax. I knew of this work, but somehow it had been lost to history until (with the help of Gould’s daughter, Abby G. Burton) I was able to find the music in the Library of Congress. Now, after almost 30 years after its composition, we are beyond thrilled to bring its first performance to Durham!

We hope that you will take from our celebration of American composers a joyful afternoon and an appreciation for their uniquely personal, optimistic, and lyrical contributions to American music.

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Copy Editor & Digital Layout: Marianne Ward

NOTES:

[1]Stehman, Dan. Roy Harris: An American Musical Pioneer. Twayne Publishers, 1983.

[2]Stehman, Dan. Roy Harris: A Bio-Bibliography. Greenwood Press, 1991.

[3] Colleen M. O’Connor’s excellent LA Times article on this topic can be found here: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-04-09-me-664-story.html

[4] Mulcahy, Richard P. “The Justice, the Informer, and the Composer: The Roy Harris Case and the Dynamics of Anti-Communism in Pittsburgh in the Early 1950s.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, vol. 82, no. 4, 2015, pp. 403–37. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5325/pennhistory.82.4.0403. Accessed 14 Oct. 2024.

[5] This exchange is captured in the Roy Harris section of Musical Visions of America: The 1948-49 Residence of Roy and Johana Harris at USAC (Utah State Agricultural College) http://exhibits.usu.edu/exhibits/show/musicalvisionsofamerica/royharris

[6] Donner’s letter: /exhibits/show/musicalvisionsofamerica/item/19759

[7] Reply of Franklin Harris /exhibits/show/musicalvisionsofamerica/item/19760

[8] Mulcahy, Richard P. “The Justice, the Informer, and the Composer: The Roy Harris Case and the Dynamics of Anti-Communism in Pittsburgh in the Early 1950s.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, vol. 82, no. 4, 2015, pp. 403–37. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5325/pennhistory.82.4.0403. Accessed 14 Oct. 2024.

[9] Mulcahy, Richard P. “The Justice, the Informer, and the Composer: The Roy Harris Case and the Dynamics of Anti-Communism in Pittsburgh in the Early 1950s.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, vol. 82, no. 4, 2015, pp. 403–37. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5325/pennhistory.82.4.0403. Accessed 14 Oct. 2024.

[10] On this topic, I highly recommend Barry Seldes’s Leonard Bernstein—The Political Life of an American Musician (University of California Press 2006).

Thank you for being a important part of the Durham Symphony Orchestra family! We appreciate your support and vital impact on our community!

This DSO is funded in part by the City of Durham and is supported by the Mary Duke Biddle Foundation, the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund and the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources).