Monday Musicale with the Maestro – February 24, 2025 – Voices of the Unarmed Project: Justice, Love, and Resilience – Part 1: Celebrating the Music and Mourning the Loss of American Composer Herman Whitfield III

Part 1: Celebrating the Music and Mourning the Loss of American Composer Herman Whitfield III

When I was the first-prize winner of the 1988 Stokowski Conducting Competition Award, sponsored by the American Symphony Orchestra, I was asked to give a brief speech before I conducted Brahms Symphony No. 1 in Carnegie Hall. The only thing I remember about the speech is that my number one ambition was to be a fervent and unflagging advocate for the American composer.

The list of American music repertoire I have conducted confirms my sincerity and consistency in keeping faith with that aim. To date it includes

- 125 Composers

- 218 Works

- 38 Premieres—including works by Pulitzer Prize winners William Bolcolm, Joseph Schwantner, Paul Moravec, and Robert Ward.

It could be that no conductor of my generation has performed more American music than I have. And of the premieres, none were more satisfying than the two opportunities I had to bring the music of Herman Whitfield III to the public’s attention.

From 1983 to 1988, I was the Associate Conductor of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra. And since then, I have been frequently invited back as a guest conductor. At the end of 2002, when asked to conduct a week of rehearsals and concerts for their main classical subscription series, I programmed music by two of my soulmate composers (Tchaikovsky and Sibelius) for the second half and the magnificent Piano Concerto by American composer William Bolcom to close the first half. It was already a technically difficult program. But the concert needed one more piece—an exuberant opening work.

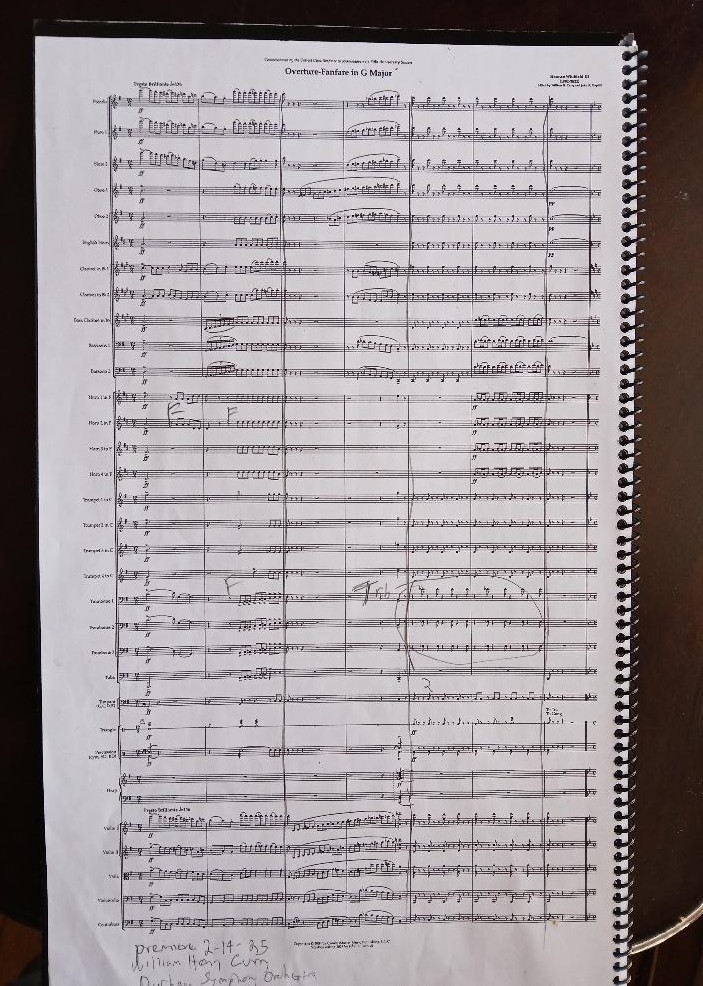

My first thought was Leonard Bernstein’s brilliant Overture to Candide, which would have been an appropriate opener. Any American orchestra has this in its repertoire, and I had already conducted the piece many times with the ISO. But things took a different direction when Linda Miller, my best gal-pal in Indianapolis, reached out to me about her co-worker’s son—Herman Whitfield III, an African American musical prodigy who had been composing since the age of 8 and was then 20. Because I love supporting creative talent, I got in touch with Herman and asked him whether he had written any works for orchestra. He immediately sent me a substantial work—his Scherzo No. 2—that had never been played.

As I studied the conductors score, I was stunned. It was a mature, lyrical, and profound work that merited being played by any orchestra in the world. I knew I HAD to conduct the premiere on my ISO concert though it would be taking a risk to add this work to an already challenging program. For me, though, it was a moral imperative to present this masterpiece by an exceptionally talented newcomer.

Herman III, nicknamed “Tre” (Italian for three) attended all the rehearsals, and I found him to be charming, modest, and bright as a dozen galaxies. The orchestra rose to the technical challenges of the piece, and it received a standing ovation. After the concert, I celebrated at a local restaurant with Tre and his parents, Gladys and Herman Whitfield Jr. We all were beaming from ear to ear, and it was on that night that my mentorship of him began. A piece of helpful career advice I offered him was that he should consider writing a brilliant, short overture for orchestra that would introduce his music to the public, conductors, and administrators—a musical calling card that would be accessible, fresh, and perhaps not as difficult as his Scherzo No. 2!

He agreed to consider that. And a few months later, he received—out of the blue—a $500 commission from a youth orchestra named the Detroit Civic Sinfonia to write a short, brilliant orchestral work. I was thrilled for Tre and urged him to accept the offer, which he did. He immediately began on the work—which, according to his parents, used new material along with passages from musical sketches he’d written when he was 19.

The work was titled Overture-Fanfare in G Major and was delivered on time to the orchestra. But there was a problem. Tre’s abundant creative spark had produced a longer and more substantial work than the commission had requested. It would have been difficult for even a professional orchestra to play, let alone one comprised of high school students! The orchestra sent back the parts and declined to give the premiere. Tre must have been disappointed. The next step would have been for him to send the score to other orchestras for consideration but neither I nor his parents know whether this happened. Perhaps the rejection of this work (due to its technical difficulty) led him to question the overall quality of the work, dampening his optimism about self-promotion. We really do not know.

Then, as now, a young composer who isn’t on the emerging-and-trending “list” created by an important handful of arts managers in New York has a hard road to recognition in front of them. For those not among “the chosen ones,” it is usually futile to send unsolicited material to orchestra administrators, hoping that someone will recognize the value of a work and program it. I have worked many times with the great American composer/conductor/author/administrator Gunther Schuller, who has this to say on the subject in his memoirs:

Over the many years of my career as a guest conductor I have been in hundreds of music director’s offices or studies, both in Europe and the United States, and I have never been in one where I did not see huge stacks of scores that had been sent to the resident conductor for their consideration. I could sometimes tell that most of them had never been looked at.

(Gunther Schuller: A Life in Pursuit of Music and Beauty 610, footnote 73)

Kudos to my American-music-conducting heroes, who looked closely at such pieces and either programmed the composers’ works or sent back their material with an encouraging note. These maestri of musical and personal integrity include the Europeans Serge Koussevitzky (who introduced Leonard Bernstein and Roy Harris to the public), Dmitri Mitropolous (who left all his money to American composers), and the American conductors David Zinman, Leonard Slatkin, John Mauceri, and Gerard Schwarz.

I feel that one of the principal responsibilities for a conductor in America is to promote our contemporary composers. Otherwise, they will be roundly neglected by:

- Audiences, most of whom are content to hear only what they already know.

- Instrumentalists, who play only what is put in front of them and have no say in the selections.

- Conductors, who are too often constrained by indifference and careerism—or are foreign-born and likely have not grown up with American music.

- Marketing departments, which inevitably opt for Beethoven—not Bolcom—and miss the new talent.

The music business is undeniably a business, but I have always insisted that one can play BOTH the audience-grabbing “Top 40” hits and worthy works by composers who should be lauded while still living and productive.

Why are the most celebrated among our composers expected to be European or dead? These days, the trail-blazing African American Florence Price receives a lot of attention, but she unfortunately died in oblivion in 1953. When I was the Resident Conductor of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, I attended the world premiere there of the wonderful opera Casanova’s Homecoming by the un-heralded American composer Dominick Argento. I had already conducted several of his pieces, and I asked conductor David Zinman, “What would it take for Dominick to be recognized as the musical genius he is?” David replied, “He will have to die first.”

I feel that it is my joy—and my job—to encourage such unheralded but talented composers and to perform their work. I hope this helps to explain why I was so thrilled to discover Tre’s work and bring it to light. This picture of Tre and me on stage after the premiere of his Scherzo No. 2 is one my favorite photos from my career.

.

Tre and I kept in touch for several years, but when he moved from Indianapolis to Miami, we somehow lost touch. And then there came the dark day in 2022 when I received an E-mail from his mother saying that at the age of 39, he had passed. And this is how that happened.

Tre was at his parent’s home when he had a mental health emergency. His parents called for medical help, but instead, police officers arrived. Tre was unarmed, unclothed, and non-threatening. Yet he was tasered, handcuffed, and put on his stomach. And then, police officers failed to turn him over as he cried out, “I can’t breathe.”

The coroner ruled that Tre’s death was a homicide, so the acquittal of those officers last December was a deeply painful and controversial ruling for Gladys and Herman, Jr. They are expecting a civil trial in a year.

For the memorial service, I asked the Whitfield’s if I could provide a brief eulogy, and I was honored by Gladys’ agreeing to read my remarks at the service, which I offer again to you here.

As someone who has devoted his professional life to promoting great music, I am beyond consolation knowing that there will be no new masterpieces coming from the mind of this young musical genius.

I want to express my deepest condolences to his parents and all of you here. Though we cannot fully imagine the grief of his parents, I think many of us have experienced a situation where we were challenged to endure something that seemed to be beyond endurance. Death is the most haunting and painful of these events. When bad things happen to good people, there is no understanding it or justifying it. The loss of a loved one is a tragic part of our life-journey that can lead our minds to dark places and negative thoughts. However, God can lead us to a positive destination where we will embrace acceptance and regain our spiritual serenity. In finding Peace, it is essential that we both preserve ourselves and our faith that in helping others, we are acting as Earth angels. Thank you for gathering here. We honor today the brief but blessed life of the Earth angel whose name was Herman Whitfield III. His spirit and his musical legacy are eternal, and today he is urging us, as we say in North Carolina, to keep on keepin’ on.

For me, the best way to honor Tre’s legacy was to play his music. I urged Tre’s mother to go into his room to find works of his that perhaps had never been performed. She agreed—and not surprisingly, it took her a month before she could steel herself to go through his music and other items. If you’ve lost a spouse or loved one and are tasked to go through their possessions, now rendered sacred by their absence, you know how agonizing an ordeal this can be. What to keep? For how long? And what ISN’T priceless that they laid their hands on?

A phone call to the Detroit youth orchestra that had commissioned “Overture-Fanfare” yielded only bad news. They had not found any trace of it, and that seemed to be the end of it—his last major orchestra work, lost to history. But Hallelujah! It was a joyous day when Gladys told me that she had found, neatly placed in one box, ALL of the parts for the Overture-Fanfare in G Major. They sent me the scores and parts via email, and I was delighted to discover that the parts were professionally engraved. So, with minimal editing by the DSO’s Randy Guptill and me—and some very productive rehearsals—we brought into the musical world this piece written 20 years ago. The DSO and I gave the work its world premiere at Durham’s Carolina Theatre on February 14, 2025.

.

.

This piece starts with a raucous fanfare that suddenly leads to the only slow, “gloomy” music in the work. But this is only the darkness before the dawn. The music unexpectedly changes to a thrilling and wild ride! Throughout, there are passages that are unpredictable and quirky—like things that “go bump in the night.” We hear sounds that seem to be coming from a fun house, or a haunted house. And it all ends with one of the most boisterous and joyful endings in American music.

Because the work was so original and required laser-like attention, it took a while for us to comprehend it fully in rehearsals. But the 3rd reading was a revelation! We recorded that rehearsal for study purposes, and after the first non-stop run-through, I literally could not contain my enthusiasm for the piece or my deep admiration for the orchestra’s ability to master it. It was then apparent that, yes, this was a masterpiece.

It’s hard to believe that this astonishingly bold and mature piece was written by someone who was only 20. As I’ve said, he was a musical genius. And I’m thrilled that his parents were our very special guests at the premiere and that they could witness the extremely enthusiastic standing ovation for Overture-Fanfare from elegant box seats above the stage. After the applause finally stopped, I introduced them to the orchestra and the audience, after which another standing ovation erupted! Nothing in my 50-year career has brought me more satisfaction than to bring Tre’s music into this world.

Gladys and Herman Whitfield Jr.–February 14, 2025- Durham, NC

We recorded the performance, and after listening to it several times, I was impressed by the DSO’s considerable achievement in surmounting the musical and technical challenges of the work. I now understand the piece more fully as being a sequel to Tre’s orchestral Scherzo No. 1 and Scherzo No. 2. A scherzo is an instrumental musical joke that is always in a fast tempo. The high spirits and sheer musical mischief of Overture-Fanfare is worthy of classical music’s first musical humorist, Franz Josef Haydn, whose irrepressible wit is found in most of his works.

Tre’s delicious musical pranks in his Overture-Fanfare strike me as being laugh-out-loud funny, something that my co-editor Randy Guptill and Tre’s parents noticed even before I did. The Whitfields were the first people outside of the DSO with whom I shared this recording. They both have listened to it many times with great pride in their son. And many tears were shed as they reflected on the tragedy of his life and the fact that there will be no more masterpieces coming from his pen. However, at the concert, they were euphoric about the piece and the audience’s eruptive standing ovations—both for their son’s piece and for their self-evident resilience.

It is with great joy that we place this work in our Monday Musicales.

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Digital Layout: Marianne Ward

“Monday Musicale with the Maestro”

would not be possible without your support!

Thank you for being an important part of the

Durham Symphony Orchestra family!

We gratefully acknowledge support from the City of Durham, Mary Duke Biddle Foundation, the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund, and the N.C. Arts Council, a division of the Department, of Natural and Cultural Resources.

.