A Post-Holiday Edition of Monday Musicale with the Maestro – May 28, 2025 – Eulogy For An American Melody Master

EULOGY FOR AN AMERICAN MELODY MASTER

In John Ireland—Portrait of a Friend, the musician John Longmire recalls the time the 20th century composer invited him to hear a recording of George Gershwin’s latest hit song, “The Man I Love.” Ireland played it for his friend three times, then began to walk around the room.

“Well?” he said in a fierce query. “What about that? That, my boy, is a masterpiece…a masterpiece, do you hear? This man Gershwin beats the lot of us. He sits down and composes one of the most original, most perfect songs of our century. Symphonies? Concertos? Bah! Who wants another symphony if he can write a song like that? Perfect my boy, perfect. This is the music of America. It will live as long as a Schubert lied or a Brahms waltz. Listen to it again and tell me I am right! (Longmire 51).

Ireland played the song for him twice more, and in writing about this experience several years later, Longmire wrote, “He was right. And I, for one, have never tired of it” (51).

We all love our favorite melodies. A great melody consists of elements of harmony and rhythm that together create an expressive effect that can soothe, inspire, energize, and sometimes create tears of joy and sadness. Some of the greatest European masters of melody have included the composers Ireland mentioned and obviously many others, including Tchaikovsky, Dvorak, and Prokofiev. Among the American standouts, I think, are Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and Charles Strouse.

Strouse, who passed away on May 15, 2025, was one of the most gifted melodists in Broadway history.

I first discovered the music written for American musicals when, at age eleven, I took home from the public library an ancient vinyl recording of Frank Loesser’s Guys and Dolls. From the opening song, I was hooked. I was thrilled by this music based on the European traditional melodies but with a distinctive American sound originating in jazz. And I found the lyrics to be easier to comprehend than the lyrics to European operas and American operettas.

Through my early teen years, I spent much of my weekly allowance money on Broadway albums, including South Pacific (Rodgers and Hammerstein), Gypsy (Jule Styne and Stephen Sondheim), and Frank Loesser’s masterpiece The Most Happy Fella. Five days a week on KDKA-FM, from 6 to 7 PM in my hometown of Pittsburgh, a complete Broadway score would be broadcast. When I was home, I never missed a broadcast of that. My love for this art form and the best of its music persists to this day.

Throughout my career, I’ve been fortunate to work with some of my favorite Broadway composers, including Marvin Hamlisch (A Chorus Line) and Burt Bacharach, whose sensational score for the musical Promises, Promises is near the top of my list of faves. In reading biographies about my song-writing heroes, I’ve noticed that many of them had roots in classical music. These include Bacharach, who studied with Darius Milhaud, and Charles Strouse, who studied with Nadia Boulanger—teacher of the American greats Aaron Copland and Roy Harris.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Strouse

In 1960 Strouse’s first Broadway show, Bye Bye Birdie, made its debut and was an immediate sensation. The music was fresh and original, much of it inspired by the early 1950s rock music performers including Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley. The title character in Birdie is an affectionate parody of the music and charisma of Elvis Presley. I first discovered this score at age 14 and loved it. I still do.

Popularity sometimes works against a light score or a comedy, keeping it from receiving the same respect as a concerto or drama. But I do NOT agree with the 20th century German composer Arnold Schoenberg, who said if an artistic work is popular, it cannot be good, and if a work is good, it cannot be popular. Though one could hardly say that Bye Bye Birdie was underrated (given its long Broadway run, 2009 revival, movie and TV versions and international success), I find much to respect about its music. There is skill and complexity here—as well as a bit of refreshing rule-breaking. An example of Strouse’s skill (and that of his lyricist, Lee Adams) can be found in the musical’s first song, “An English Teacher.”

This is a song sung by Rosie to her romantic interest, Albert, a songwriter and the manager of Conrad Birdie, who has been unexpectedly drafted into the army (a situation parallel to the 1958 drafting of Elvis.) In this song, she pleads with Albert to leave the “trashy” world of pop music and “ascend” to the “classier” world of academia. Breaking the old “rule” that 32-bar melodies should be repeated while only the lyrics change, this song instead features an evolving melodic line which is ingratiating while disguising its relative complexity.

After Birdie, Strouse wrote a succession of hits including Annie and Applause. Those of us of a certain generation will also remember the song “Those were the Days” from the opening credits of the 1970s TV show All in the Family. But many may have missed the notice in the end credits that the song was written by Strouse and Adams!

Note how the lyrics in that 1970 song slyly refer to a certain point of view about issues that our country is STILL embroiled in! This article from NPR is a wonderful tribute to the man—capturing a sense of his personal warmth and humor:

https://www.npr.org/2025/05/23/nx-s1-5407524/remembering-broadway-composer-charles-strouse

My favorite singers are especially gifted in using lyrics to reveal the message and atmosphere of the song. Such singers include Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, and today’s current master of The Great American Songbook, singer-pianist Michael Feinstein.

Michael is also an archivist, an activity that began at age 21 when Ira Gershwin hired him to catalogue his mammoth collection of recordings and music, including musical manuscripts by Ira’s older brother, George. Michael and I first worked together twenty years ago with the Syracuse Symphony Orchestra. Between rehearsals and concerts, we enjoyed touring used bookstores and talking about the music of Broadway. He expressed genuine surprise that a symphony conductor like me would know as much as I did about the composers who wrote virtually all of his repertoire. He told me then that he was friends with Charles Strouse, and so when Strouse passed away on May 15, 2025, at the age of 96, I reached out to Michael during his busy week of concerts in San Fransico to tell me about his association with Strouse.

Strouse (known as “Buddy” by his friends) told Michael about his early years honing his craft at summer music camps and studying with Nadia Boulanger. Their personal relationship included plans for a Strouse/Feinstein album, but only four tracks were completed because Strouse was such a perfectionist that he kept endlessly changing his mind about tempi and style. Strouse and Feinstein are two of the greatest musicians of our era, so I hope that eventually these musical gems will be released.

That sort of perfectionist streak informs most great creative work, and I believe in the veracity of the saying, “God is in the details.” Yet over-thinking and excessive self-doubt can take its toll on an artist’s creative work and mental health, and when this happens, it is also true to say, “The devil is in the details.” As a composer, I call myself the “King of the 49th Draft,” which means I have sometimes driven my editors and engravers to doubt their sanity for continuing to work with me. Indeed, Feinstein thought that Charles Strouse’s output might have been even larger if not for his compulsion to tinker with the slightest details in his quest for perfection. Feinstein believes that the same problem afflicted Burton Lane, the brilliant composer of Finian’s Rainbow, Royal Wedding, and On a Clear Day You Can See Forever.

I’m grateful that Michael’s role as a musical archivist, unearthing unknown musical treasures for the public, has brought to my attention a remarkable song by Burton Lane with lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner (My Fair Lady and Camelot) from a forgotten musical called Carmelina.

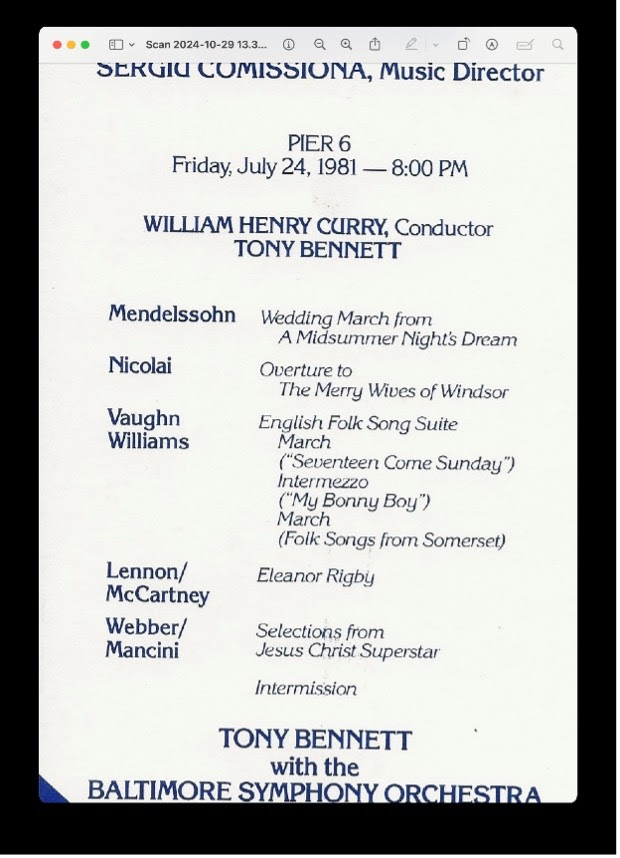

Once upon a time, from roughly 1920 to 1970, Broadway musicals produced many of the era’s most popular songs. Charles Strouse wrote a half dozen which were enormous hits, including “Put on a Happy Face” (the title of his highly enjoyable memoir) from Bye Bye Birdie, “Tomorrow” (from Annie), and “Once Upon a Time” (from All American). This latter song had the good fortune of being on the flip side of singer Tony Bennett’s 1962 hit “I Left My Heart in San Franciso” by the song-writing team of Cory and Cross. “Once upon a Time” has been recorded by over two dozen artists and is my favorite of the songs by Strouse and Lee Adams. The lyrics evoke bygone days of youth and young love. Matching the words is a bittersweet melody, a poetic miracle any composer would have been proud to have written. I had the good fortune of working with the late Tony Bennett several times, and the highlight of my time with him was conducting his performance of this song.

Here is his recording from 1962.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VmwApZaMNe0

In my junior high school years, having discovered the glory of great classical music, my curiosity led me to explore and to love many different genres of music that I found to be equally thrilling. For me, a great melody is a great melody whether it derives from classical, jazz, pop, or folk music, or from film, Broadway, or television.

I understand John Ireland’s love for Gershwin’s song “The Man I Love.” Most classical musicians of his (or our) time would not understand his enthusiasm for something out of the classical mainstream. But for me as a composer, the quality of the melody is the number-one essential. It must be expressive and sincere in its portrayal of moods from the poignant to the powerful. And it must be logically constructed. As Aaron Copland counseled me, “The piece should seem to be composing itself.”

While I am not conscious of any specific composers influencing my own music, I have studied a wide variety of melodies to understand their ability to communicate human feelings, including those by classical composers such as Tchaikovsky and Aaron Copland and “pop” composers like Richard Rodgers and Michael Jackson. As a music-lover, I refuse to be boxed in by cultural conformity, and I can embrace with equal fervor an operatic aria by Verdi and a song from Abba. I agree with “Duke” Ellington, who said more than once in interviews, “If it sounds good, it IS good!”

William Henry Curry

Music Director

Durham Symphony Orchestra

Comprehensive Editor (Text): Suzanne Bolt

Copy Editor & Digital Layout: Kelly Adolph and Marianne Ward

This DSO is funded in part by the City of Durham and is supported by the Mary Duke Biddle Foundation, the Durham Arts Council’s Annual Arts Fund and the N.C. Arts Council (a division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources).

|  |  |